A Tale of Two Warblers

Both were on the original Endangered Species List in 1973, and both have now been delisted, for opposite reasons.

(Listen to the radio version here.)

When the Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973, the first official Endangered Species List included two warblers of the United States that, by 2024, had both been delisted. (Current Endangered Species List is here.) In one case, this was for a happy reason; in the other, a tragic one. Both Bachman’s and Kirtland’s Warblers were already quite rare when Europeans arrived in America. Now one has disappeared entirely while the other is thriving.

Both Bachman’s and Kirtland’s Warblers were named for men who went by the title “Doctor,” one a minister, the other a physician. Dr. John Bachman, the minister, collected and skinned the first known specimens of the warbler named for him in 1832 near his home in Charleston, S.C., and sent them to his close friend Audubon, whose two sons married Bachman’s daughters. Audubon based his painting on the specimens; he never saw a living Bachman’s Warbler.

The breeding range of Bachman’s Warbler apparently extended throughout the Southeast, primarily in the southern Atlantic coastal plain and the Gulf Coast states north along the Mississippi watershed to Kentucky, and it wintered mostly in Cuba.

But the birds were difficult to see and hear, and few were studied, so most of what we have to go on were the brief notes about location and, occasionally, habitat descriptions accompanying specimens shot by collectors, so there are a lot of uncertainties, but it seemed to have nested in bottomland swamps with pools of still water. It may or may not have been a cane specialist and may or may not have been a colonial breeder.

Even after the species was named and painted by Audubon, it remained in relative obscurity until selective logging in the 1880s briefly made it more common. Most of the information about breeding birds was recorded between the 1880s and 1910s, when clearcutting became the method of choice for logging in its range, and the species became very scarce.

The last definite winter record of Bachman’s Warbler was made in 1940, and the last specimens collected were on Islands off Mississippi in 1940 and 1941. The only known sound recordings of a singing Bachman’s Warbler were made in 1954 near Washington DC by Arthur Allen, and in 1959 by G. Stuart Keith near Charleston, South Carolina. The last known color photograph of a living Bachman’s Warbler in the wild (and perhaps the only one) was taken by Jerry A. Payne in 1958.

The last non-controversial sighting of a Bachman’s Warbler was in 1988. The species was removed from the Endangered Species List in 2023 because it was declared extinct.

The first specimen of Kirtland’s Warbler was shot at sea somewhere between the Abaco Islands of The Bahamas and Cuba in mid-October 1841 by Samuel Cabot III. It was kept in a private collection, not recognized as a new species until it was too late to become the type specimen. It made it to the Smithsonian Institution in the 1860s while, meanwhile, in May 1851, one was collected on Dr. Jared P. Kirtland’s property near Cleveland, where Dr. Kirtland was a noted physician. This specimen was sent to Spencer Fullerton Baird, curator of the Smithsonian, who named it for Kirtland. In his original account in 1852, Baird attributed the specimen’s collector as Charles Pease (Kirtland's son-in-law), but by 1858 he had changed his story and was attributing it to Kirtland. Audubon never painted Kirtland’s Warbler—indeed, he never knew it existed; he died in January 1851, a few months before that first Ohio bird met its untimely end.

No one knew where Kirtland’s Warbler nested until a University of Michigan student collected a specimen near the Au Sable River in Osceola County, Michigan, in 1903. He brought it to a taxidermist, Norman Asa Wood, who returned to the site and collected the two nests he found, both with chicks and one with an unhatched egg. He tried to raise the chicks, but they all died. Those nestlings and the adults he shot, 15 birds in all, comprised the largest collection of Kirtland’s Warblers at the time.

Not a single nest was found further than 60 miles from that site until 1996. Half a century ago when I started birding, the entire breeding range was still restricted to a few counties in the northern part of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. In 1974, an extensive census found only 167 singing males on the entire range, making it among the rarest species on the planet.

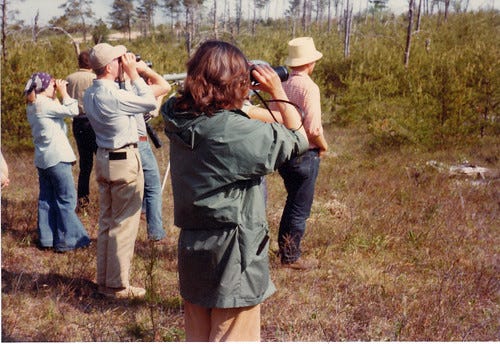

I lived in Michigan in the mid-70s, when Kirtland’s Warbler was named Michigan’s “Bicentennial Bird.” Conservation agencies and organizations were working tirelessly to build up the population to 200 singing males by 1976, the nation’s Bicentennial and the year I saw my lifer.

They barely succeeded in getting the bird’s numbers up to 200, but even with protection and habitat enhancement, the species had its ups and downs for a while—in 1987, over a decade after that low, numbers were again down to just 167 singing males. Researchers set a benchmark of 1,000 singing males as their goal.

Thanks to the protections, habitat management, and control of cowbirds in Kirtland’s Warbler nesting areas, all provided thanks to the Endangered Species Act, Kirtland’s Warbler is thriving, and can now be found in a much broader swath of the Lower Peninsula, and also in the Upper Peninsula, Wisconsin, and Ontario. That magic number of 1,000 singing males has been exceeded every year since 2000, and the 2021 census set the current number at 2,245 breeding pairs.

I don’t know if Kirtland’s Warbler will live happily ever after, but it’s doing darned well now, so it made sense to take it off the Endangered Species List in 2019, giving its story a much happier ending than that of Bachman’s Warbler.

Wonderful news and great photographs! Thank you!

Conservation success is the Kirtland's. However, studying extinct birds and why they went extinct leads to the best conservation management practices. I lump them in similarity duos. These two warblers, the Carolina Parakeet and another migratory parrot, one of two left, Australia's Swift Parrot, Critically Endangered, and the US Extinct Ivorybill, and the US Endangered Red-cockaded Woodpecker. Lessons learned. But yet wait. The IUCN has the Ivorybill as Critically Endangered. A new analysis of previous vocal data has confirmed the supposedly ivorybills. It's being reviewed by experts. It's slated to be published by July 7, I believe, but I'm not sure the review process will be on time. Do you have an organization I can send it to with attention to you in the subject?