Ancient Murrelets!

Why do birds of the Northern Pacific wander inland? Your guess is as good as mine.

(Listen to the radio version here.)

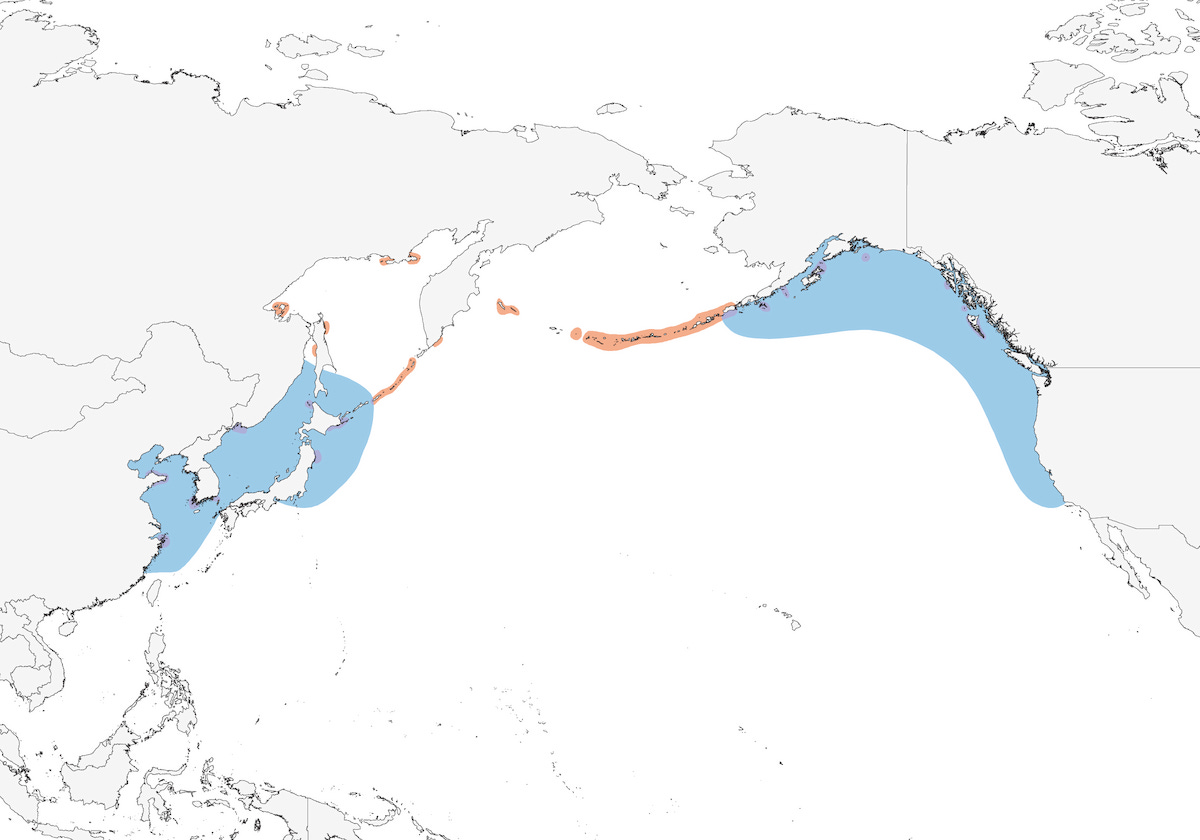

On Saturday, December 9, I got a text message that an Ancient Murrelet was being seen in Two Harbors. This diminutive oceanic bird breeds in the northern Pacific rim from China to British Columbia, and winters in the northern Pacific, especially in waters off Russia, Japan, and China in the west and from Alaska down to California in the east.

It was barely a week after my surgery and so riding in the car was still uncomfortable and I was still getting exhausted easily; I decided not to chase it. I probably would have risked it if it would have been new for Minnesota, but I’d seen one off Stoney Point on January 17, 2021.

I’ve also seen them where they belong, first when Russ and I took a cruise on a tiny, Native-owned ship up Alaska’s Inside Passage in 2001 and also on our boat trip in the Kenai Fjords in 2022, but I didn’t get any photos either time. I did get a few distant ones when Russ and I were on a ferry in British Columbia in November 2014.

No older than other birds in its family, people can’t help but wonder why this murrelet was named “ancient.” The standard explanation is its gray back, but Kenn Kaufman recently looked into some original descriptions of the species going back almost 240 years and learned that Thomas Pennant, who studied museum specimens of this murrelet in its breeding plumage, wrote in his Arctic Zoology in 1784: “on the hind part of the neck are numbers of white, long, loose, and very narrow feathers, which give it an aged look.” This is not a feature most of us get to see in person—inland sightings are never made of breeding birds, and the ones I saw in Alaska weren’t close enough for me to see those feathers, but this is the feature apparently used by Gmelin when he gave the bird its official name in the 13th edition of Systema Naturae in 1789.

Ancient Murrelets are true oceanic birds who feed on small fishes and large zooplankton, especially crustaceans called “krill.” They forage chiefly in offshore waters to the edge of the continental shelf but can also occur in large numbers within a few kilometers of land where tidal upwellings bring food close to the surface.

They don’t come to land except to breed, usually in colonies. Each pair digs a nest burrow in soft soil or uses a cavity under tree roots or a shallow hole under a tussock of grass. Once in a while, a pair uses a rock crevice. Tragically, their nests are fairly accessible to predators: at one colony in British Columbia, raccoons wiped out all the breeding birds over two-thirds of the nesting island. Adult mortality is fairly high compared to other birds in the puffin family, but when both birds of a pair survive, they tend to choose one another as mates year after year. One pair was found using the same nest burrow for six successive seasons. Ancient Murrelets produce many vocalizations, mostly calling at night from nesting colonies—the sounds attract new breeders.

Females lay two eggs, and hatching success is high. Despite their small size, the parents take extended incubation shifts, from 2 or 3 days when food is abundant, and up to 6 days when the bird off the nest must travel further to get enough food. Sometimes both parents may be off the eggs for a day or two, even in the middle of the incubation period; fortunately, the eggs are very resistant to chilling, hatching successfully even if deserted for 24 hours in late incubation or while the chicks are pipping.

This is the only seabird in which the parents never carry food to the nest. The chicks hatch with thick down feathers, their eyes open, and plenty of body fat to sustain them until, within a few days—usually two—the family departs for the sea. When a nesting colony’s path to the ocean is fairly flat, a few families may stay together along the journey, but usually, especially on steep terrain, the parents fly to the ocean and wait for their young to waddle and slide their way down. The family members find each other thanks to recognizing one another’s calls. Parents remain with their young for at least a month, until the chicks are fully grown. Even after the family goes their separate ways, they’ll stay on the ocean until the next breeding season.

So what the heck could such a truly oceanic bird be doing in Two Harbors, Minnesota? Oddly enough, there are quite a few records of Ancient Murrelets long distances from the ocean—this is by far the most likely bird in its family to occur well inland. Records have been documented by specimen or photograph as far south as Nevada and New Mexico and as far east as Quebec and Pennsylvania, with multiple records for many provinces and states—there are at least 9 records for Minnesota now! One analysis suggested that most inland records are associated with storms on the Pacific coast, the easternmost records being associated with more northerly storms.

For some mysterious reason, the fall of 2023 appears to have sent an exceptional number of Ancient Murrelets inland in the eastern half of the continent.

In November and December there were sightings from all five Great Lakes if you count Green Bay as part of Lake Michigan. Minnesota had our Two Harbors sighting; there were sightings in Ashland and Sturgeon Bay in Wisconsin; and in Lorain, Ohio, on Lake Erie west of Cleveland. Ontario borders four Great Lakes, and birders on that side of the border saw them from the shores of Lake Ontario and Huron all the way to Thunder Bay on Lake Superior.

Perhaps the most extraordinary of all the Ancient Murrelet sightings of late 2023 was one that turned up in Tennessee at Chickamauga Dam near Chattanooga. I found out about that one because I got a Google alert on my own name—a Tennessee newspaper article cited a blog post I wrote in January 2021 about the Ancient Murrelet at Stoney Point and how it reminded me of the little bird described so lovingly in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s The Long Winter, set in what is now De Smet, South Dakota. In the chapter “After the Storm,” Pa Ingalls walked into their cabin after a terrible October blizzard that lasted days holding a bird he’d found tucked into a haystack. Wilder’s description matches that of an Ancient Murrelet.

Birders with keener eyes or more confidence than me looked carefully at photos of the eBird documenting photos from this season to conclude that all or at least most of them were different individuals. As of this morning, January 10, 2024, there haven’t been any inland sightings reported to eBird since the new year—not the best news for birders, but good news for the murrelets themselves, who really do belong in northern Pacific waters.

I remember seeing these birds when I lived for a while in Cordova, Alaska. Thank you for the great information and the photos. I agree, best not for them to be in Minnesota.