Blue-gray Tanager!

Almost the first tropical bird I ever saw

(Listen to the radio version here.)

I’ve always liked numbers, so for a great many years, I wanted to do something on 01-01-01 as spectacularly unique as that auspicious date. And sure enough, that was the day on which, for the first time in my life, I traveled outside the United States or Canada. I’d stayed with my aunt and beloved godfather while he was dying in 2000, and at his funeral, my aunt asked me what the place of my dreams was. When I was very little, I’d seen a picture somewhere of the Resplendent Quetzal and obsessed about it for a long time, so I answered, Costa Rica. And that’s where I was now headed.

I arrived at the San Jose airport late at night so didn’t see a single tropical bird on 01/01/01, but first thing the next morning I glimpsed at the feeding station outside the dining room of the Hotel Bougainvillea and saw two instant lifers—Palm Tanager and Blue-gray Tanager.

Palm Tanagers seemed dull and nondescript—it took years for me to appreciate the ethereally strange yellowish-olive tinge to their gray heads. I wonder how they appear to one another with their ability to see colors in the ultraviolet spectrum. But in 2001, my eyes were hungering for tropical brilliance so they instantly jumped to the lovely blue bird beside it, a Blue-gray Tanager.

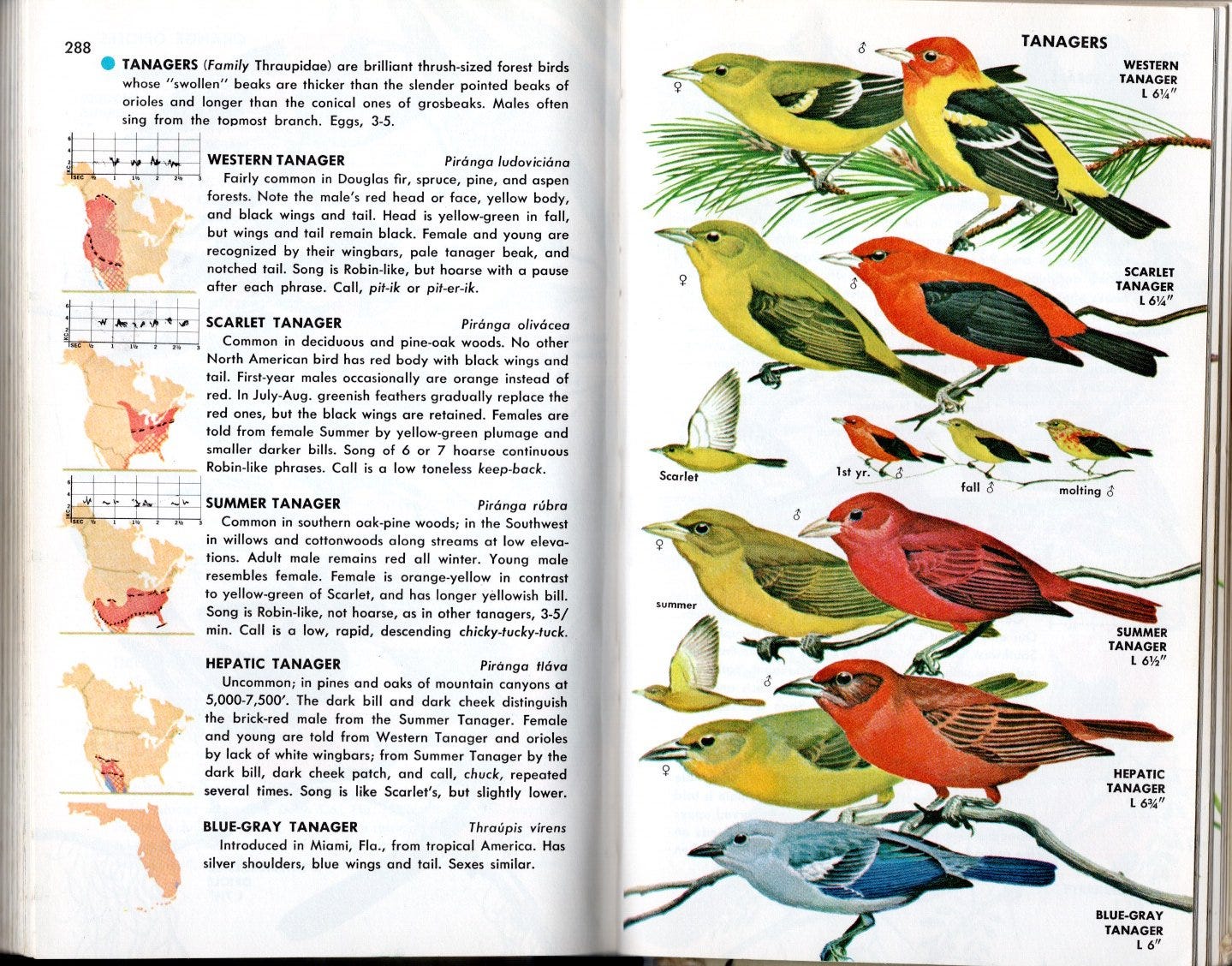

Oddly enough for a person who spent the first quarter century of her birding life intentionally avoiding reading about birds outside the United States and Canada, I’d been familiar with the Blue-gray Tanager all along because, believe it or not, the species was included on the tanager page in my Golden guide!

I wondered why it wasn’t in my Peterson guide, but the answer was pretty simple—no one had ever seen one anywhere in the United States at the time my Peterson guide was published in 1947. The Golden guide was published in 1966, in the middle of a very brief period when it appeared that an introduced population of Blue-gray Tanagers was becoming established in south Florida.

Blue-gray Tanagers were popular aviary birds back then, and apparently some escaped or were released near Miami. In 1961, I.V. Arnold reported in Florida Naturalist that the species had been discovered in Hollywood, Florida in 1960. Paulson and Stevenson reported in Audubon Field Notes that the species had nested in the Hollywood area in 1961 and 1962. A singing male was collected on the University of Miami campus in 1964. In 1972, Ogden wrote in American Birds that the species was increasing and continuing to breed in northern sections of Dade County. And in 1976, Paul DeBenedictis wrote in American Birds that because introduced species are included in the American Birding Association’s checklist if they have bred unaided by man for at least ten years, the status of the Blue-gray Tanager in south Florida deserved review somewhere in the literature.

But when the second edition of the Golden guide came out in 1983, the Blue-gray Tanager had been removed. Despite those isolated cases of successful breeding in Florida, the species never became truly established and was disappearing by the late 70s. The only birders today who have the Blue-gray Tanager on their ABA Continental list must have seen it in south Florida in 1982 or earlier. I didn’t know any of those details when I saw that first one in Costa Rica in 2001—just that it was every bit as pretty as Singer’s illustration in my Golden guide.

Blue-gray Tanagers may not be found wild in Florida, but they’re extremely widespread from southeastern Mexico to central South America. I saw them almost every day on that first trip to Costa Rica, every single day when Russ and I were in Trinidad and Tobago later that year, and many times on my trips to Panama, Peru, Ecuador, and Guyana. Males and females are identical.

Blue-gray Tanagers are a frequent visitor at feeders offering fruit, where other tanagers are regular visitors, too, but unlike many tropical members of their family, Blue-gray Tanagers don’t typically join mixed flocks. Several Blue-grays will come to a feeder or fruiting tree together, eat a while, and then leave together, paying no mind to what the other birds are doing. Besides fruit, they eat a variety of insects.

My closest encounter with a Blue-gray Tanager—and the only time I’ve ever held a tropical bird in my hand—happened in 2007 in Costa Rica. Our group had stopped for lunch at an outdoor café, and suddenly Kevin Easley, our guide, noticed one strike a car window. It was stunned, and since Kevin knew I was a licensed rehabber in the States, he asked me to take a look at it. The bird sat in my hand for several minutes as everyone took close looks and photos.

Then it pooped on me and flew away.

I found myself fascinated by the gelatinous, translucent glob glistening in my hand, the color and consistency of the inside of a grape—bird droppings can provide interesting insights into their diets.

I’d been a rehabber for many years and spent a lot of time reminding my children to wash their hands after touching them, so I can’t imagine how upset I’d have been if they’d ever neglected to wash thoroughly after a bird actually pooped on them, but apparently my fascination caused some critical parts of my brain to disengage. I wiped my hand with my paper napkin, tossed it out, and went back to eating!

I got very sick—I was glad I had the Cipro my travel clinic had supplied me with before the trip. I of course didn’t hold my own stupidity against the poor little bird, and 19 years later, the memory of how that glob of poop looked is much more vivid than the memory of my being sick. Indeed, I’d forgotten all about it until I started gathering information about the species and looked at my photos. Oops!

The experience left me with both a cautionary tale and a funny story to boot. Tragically, more than half the birds that hit windows and fly away end up dying from hematomas or other internal injuries, so I hope this poor little bird lucked out and fared better than I did from our encounter.

I hadn't known about the brief history of Blue-gray Tanagers nesting in FL, but it explains my confusion for many years thinking is was a North American bird!! LOL!

I must say that I don't think you should blame tanager poop for your getting sick. Perhaps more likely you can thank something you were served to eat at the time! Just sayin'! ;)