(Listen to the radio version here.)

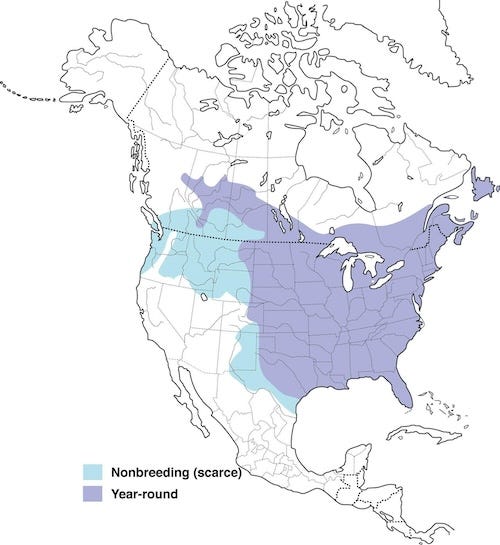

One of the great unsolved mysteries of the bird world is connected to one of the great ironies of human nature. First the mystery: no one has ever figured out Blue Jay migration. Look at any range map of the species and you’ll see that Blue Jays remain in the furthest southern reaches of their wintering ranges all summer, and in the furthest northern reaches of their breeding range all winter. A standard range map would suggest that, except maybe in the West, the Blue Jay is entirely non-migratory.

Range maps are simplified. Maps generated by eBird from actual bird sightings provide much more nuanced information, yet comparing these three eBird maps shows pretty much the same thing: there are Blue Jays way up north even in the dead of winter and way down south even during mid-summer.

A wonderful animation created by experts at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology uses the number of Blue Jays reported on eBird checklists week by week to show that even as the range stays pretty much the same, Blue Jay abundance changes here and there over the year. (Producing such accessible and useful tools takes a lot of resources. Please support the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s extremely valuable work!)

Still, the idea that Blue Jays migrate defies most of our personal experience. Wherever we live within their range, we can see Blue Jays throughout the year. How can they possibly be migratory?

Yet they most certainly are. As of September 4, the counters at Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory, just above my neighborhood, have already counted 2,804 Blue Jays passing by this year. (Check out the current 2024 count total here.) The count for each of the past three years broke the previous record. The total for 2021 was 59,602. The count topped 60,000 in 2022. (I can’t find the non-raptor totals for these years on the Trektellen site.) Last year the total of 78,629 shattered that record.

This does not mean that Blue Jay migration during the last three years was the biggest ever—historically, the counters at Hawk Ridge counted only raptors, and it’s only been in recent years that they’ve counted songbirds at all. Back in the 1980s and 90s, we used to keep a songbird count at the Lakewood Pumping Station but weren’t as systematic as the counters now are, and that data isn’t easily accessible anymore. I do remember thrilling at lovely days with over 1,000 jays winging past—our Blue Jay migration here has always been impressive.

Like other migrating birds, these Blue Jays are headed southwest, parallel to Lake Superior. Birds migrating by day try to clear the lake before heading more directly south because dangerous downdrafts can occur over water. Also, migrating Blue Jays seem to fly only short distances—a few miles at most—before stopping to feed and rest as they mosey along. Lake Superior doesn’t provide any places to land.

People have observed and studied Blue Jays for centuries, but we still cannot predict accurately whether an individual Blue Jay will leave or stay in any particular year. Many young jays migrate but many don’t, and many adults migrate but many don’t. Indeed, many individuals have been reported migrating some years but not others.

And this brings us to a great irony of human nature. I often hear people speculating about contacting and communicating with “intelligent life” on other planets, in other solar systems. My favorite episode of the original Star Trek, “The Devil in the Dark,” has Spock undergoing a “mind meld” to communicate with the Horta, a silicon-based creature in a galaxy far away.

In the movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind, we feel an exquisite triumph at the end when musical notes provide a mode of communication between humans and the aliens.

In the non-fiction realm, back in the 1970s, scientists beamed their first message to extraterrestrials in outer space. The binary-coded radio-signal transmission contained basic information about us including a stick figure of a person, representations of DNA, our solar system, and a graphic of the telescope that sent it. This seemed to be a human-centric version of Dr. Seuss’s Horton Hears a Who, our high-tech message beamed 25,000 light-years away simply saying “We are here! We are here! We are here! We are here!”

But if we’re that lonely, yearning so badly to connect with intelligent life "out there"—intelligent life that we’re not sure even exists—why haven’t we tried at all to connect with intelligent life right here on this planet? Why doesn’t science fiction ever imagine Spock mind-melding with a Blue Jay? Well, okay—in the fourth Star Trek movie, “The Voyage Home,” he does mind meld with a whale, but Blue Jays could have told him a lot of useful information about what was happening on the planet, too.

Why don’t we have a sci-fi movie in which scientists work together in an existential struggle to find a way to communicate with Blue Jays? We’d call it Close Encounters of the Bird Kind. I mean, they’re just as talkative as we are. You’d think we could ask them what the heck’s going on with their migratory habits.

But in a cosmic irony, our excessively imaginative and communicative species cannot imagine communicating with Blue Jays. Maybe one day we’ll hear back from a distant galaxy only to learn that the life forms we’ve been yearning to contact for so long, at such expense, have been communicating with birds all along.