Bucephala!

Goldeneye is not just a James Bond movie.

(Listen to the radio version here.)

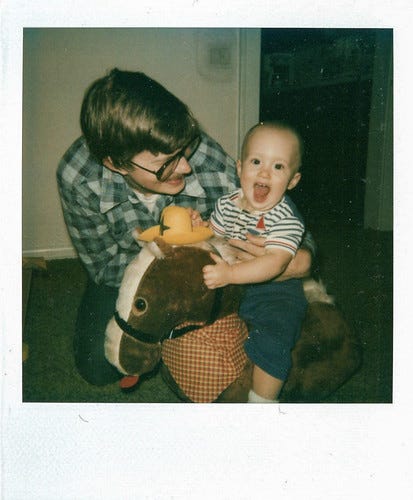

On our baby Joey’s first birthday, we gave him a plush rocking horse designed to accommodate a toddler’s short legs, with an oversized head for a little one to hang onto for balance. Since Joey wasn’t doing much talking yet, we had naming privileges, and I decided to call the horse Bucephala after Alexander the Great’s horse (Βουκεφᾰ́λᾱς). I’ve seen the horse’s name written as Bucephala or Bucephalas—either way, it’s Greek to me. The real-life horse, like Joey’s, was named for his large, ox- or bull-sized head.

I’m hardly a student of ancient Greece—the only way I know anything about Alexander the Great or his horse is because when I was learning scientific names in my first ornithology class, I looked up Bucephala—the generic name for the Bufflehead, a little duck I’d seen the spring before I took the class.

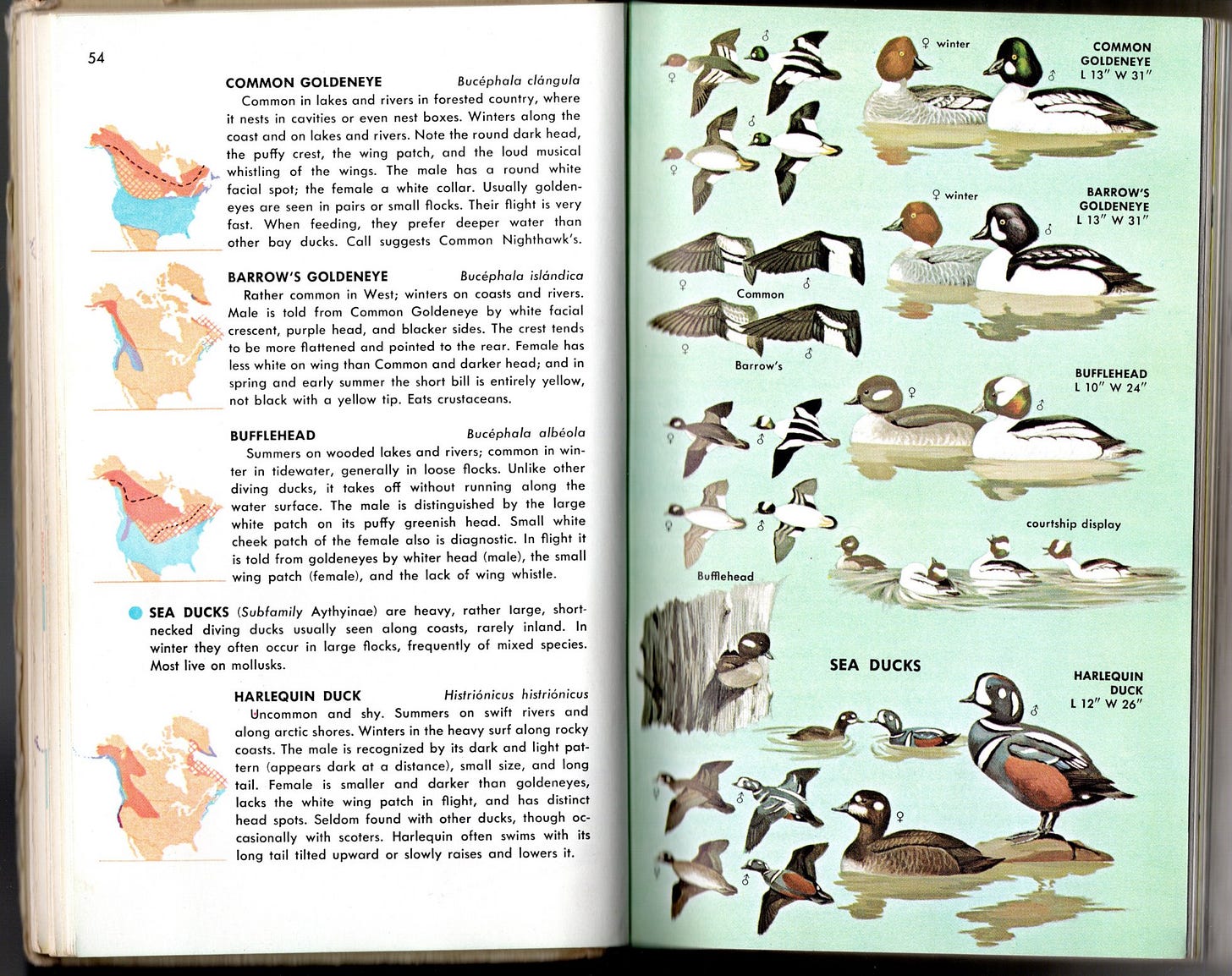

Linnaeus named both the Bufflehead and the Common Goldeneye in 1758, but I don’t know if he was referencing Alexander the Great’s horse or simply using the Greek term for an oversized head.

The Bufflehead’s scientific name is Bucephala albeola, the specific epithet referring to the white on the male’s head. Its English name also refers to its relatively large head size, meaning quite literally “buffalo head.”

The Common Goldeneye’s specific epithet, clangula, refers to the loud sound produced by the birds’ wings in flight, which can be heard and recognized for quite a distance, explaining its most popular nickname, “whistler.”

Common Goldeneyes nest near lakes and rivers of boreal forests across Canada and the northern United States, Scotland, Scandinavia, the Baltic States, and northern Russia, usually in tree cavities. Human density on appropriate habitat within their nesting range is low, but when thoughtful people set out nest boxes, goldeneyes often use them.

Common Goldeneyes live up to the name “sea ducks,” wintering along the coasts, but also inland where lakes and rivers stay open. Every winter, some gather around the ship entry in Canal Park in Duluth.

They dive for their prey, which overall is roughly 32 percent crustaceans, 28 percent aquatic insects and 10 percent mollusks. Insects are the predominant prey while nesting; they switch more to crustaceans during migration and winter, at least in most places. One 1996 study found that among the goldeneyes wintering on the Great Lakes, about 79 percent of the diet is invasive zebra mussels. We birders can’t usually see what diving ducks are eating because they swallow most of their prey underwater, but in Canal Park and the Superior entry at the end of Wisconsin Point, we can sometimes watch goldeneyes scraping zebra mussels off the walls of the breakwater.

Every now and then, I luck into seeing a Bucephala of a third species—a Barrow’s Goldeneye.

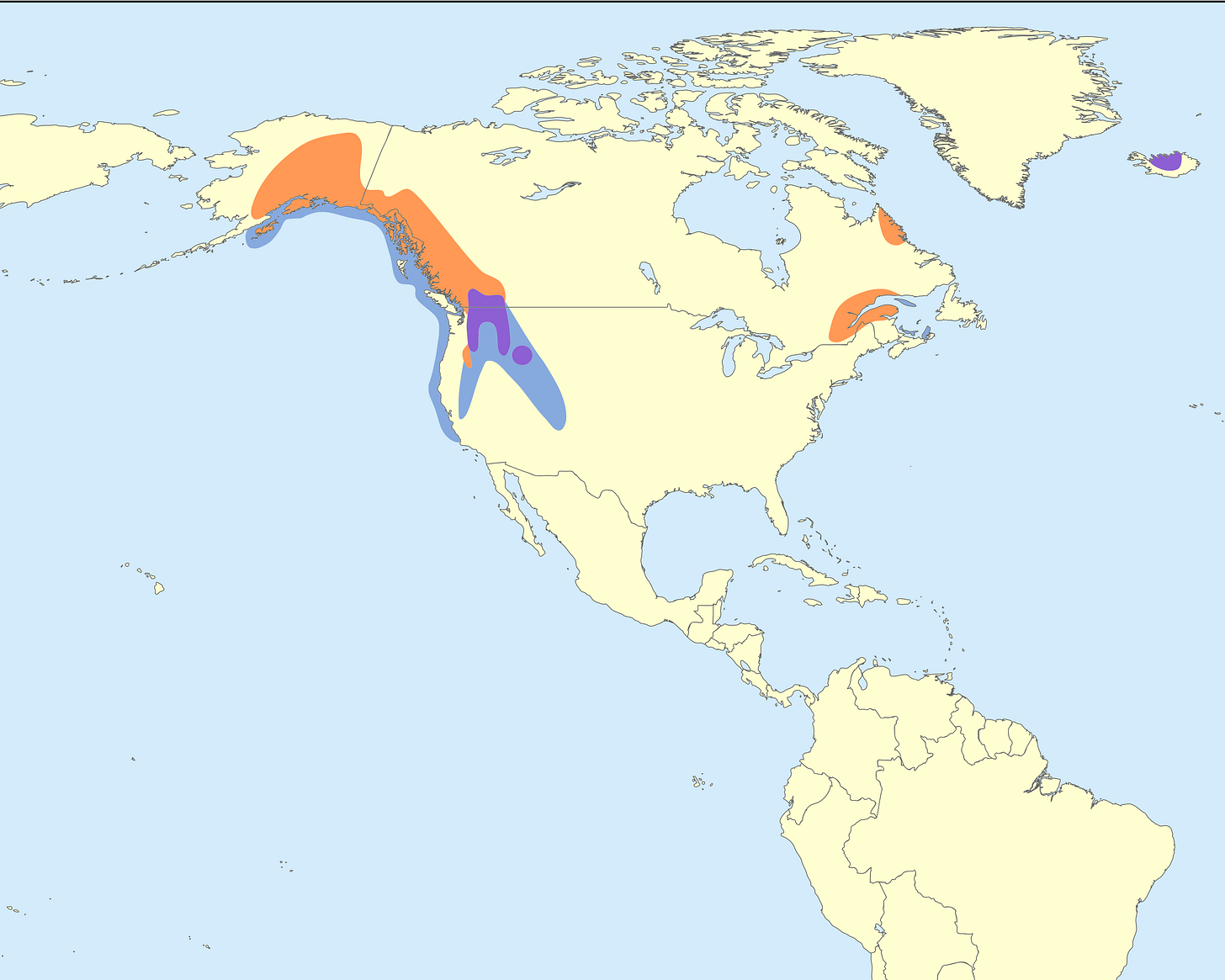

This beautiful duck is chiefly a bird of the western montane region of North America; it was once referred to as the “Rocky Mountain Goldeneye,” and sure enough, I saw my lifer in August 1979 in Yellowstone National Park; I’ve also seen them in California, Alaska, and British Columbia.

Occasionally in winter, a single individual Barrow’s Goldeneye turns up right here in Duluth, Minnesota; or Superior, Wisconsin, hanging out with Common Goldeneyes.

Barrow’s Goldeneyes have a small, disjunct nesting population in eastern Canada and another in Iceland, which is where the species was first collected and described for science by German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1789; he gave it the specific epithet islandica for Iceland. This may seem odd to us Americans, but Gmelin named it before Europeans were doing much exploring in western America—the Lewis and Clark Expedition didn’t begin for another 15 years, and they never saw a Barrow’s Goldeneye.

Barrow’s Goldeneyes are common around Lake Mývatn in northern Iceland, where local people have traditionally created nest boxes for them on the sides of their homes and barns, explaining the local name for the species, húsönd, which means house duck. The origin of the Iceland population is unknown—the species isn’t known for vagrancy. Barrow’s Goldeneyes are rare but local on the coast of Greenland, but there are only a handful of records of them wandering as far as Scotland, and nowhere else in Europe.

A great many Barrow’s Goldeneyes died in the aftermath of the March 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill because so many of them winter in shallow mussel beds along the Alaskan coast. Thinking about that still breaks my heart, and makes me feel ever more committed to protecting this fragile planet for all of our natural community.

I want to give a special shout-out to everyone with a paid subscription. I’m committed to making all of my content free for everyone, but this Substack blog is my primary source of income and must cover my birding and photography expenses. Thank you, paid subscribers, from the bottom of my heart.