Connecticut Warbler

Seeing this bird involves the 3 Ps: Patience, Perseverance, and Providence.

(Listen to the radio version here.)

Last Monday, when my friend Paula Lozano and I went to the Sax-Zim Bog, we heard a Connecticut Warbler singing far off from McDavitt Road. Had this been almost any other species, we couldn’t have heard it from that distance, but Connecticut Warblers have a wonderfully loud song. We felt lucky—we’d spent early morning at a different spot, and by mid-morning when we arrived here, most birds had stopped singing.

An hour or so later, we encountered two birders from Massachusetts who’d been desperately searching for a Connecticut Warbler all day. They spent a lot of time on McDavitt Road in early morning and had heard the singing, too, they but they wanted to see a Connecticut Warbler and seemed annoyed that there wasn’t easy public access directly to one.

I can’t say how many people over the years have asked me how to see a Connecticut Warbler. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds species account begins:

The Connecticut Warbler is an infamously hard-to-find bird that forages on the ground in remote muskeg, spruce bogs, and poplar forests… Although males sing from trees, this species forages by walking slowly through underbrush, where it is difficult to see. Probably owing to its retiring habits and remote habitats, Connecticut is among the least studied of American songbirds.

I never saw a Connecticut Warbler while we lived in Michigan, and if I heard one, I didn’t recognize the song yet. I lucked into my lifer in Wisconsin in May 1978 when I was doing a Big Day, and found another migrant at my favorite Madison birding spot, Picnic Point, the next year. After moving to Peabody Street in 1981, I started seeing them more regularly, often in my own backyard, during spring and fall migration. But I’ve never seen any Connecticut Warbler without feeling like Providence was shining on me.

Starting in the 90s, my sightings of migrants grew fewer and farther between, and I haven’t seen one on Peabody Street in years. By the time I got my first good digital camera in 2009, any sighting felt like pure luck. Photos? Even getting a poor one felt like finding the Holy Grail.

The vast majority of birders who see Connecticut Warblers find them, as I’ve found most of mine, during migration. The species breeds in a narrow band of coniferous forest from western Quebec to eastern British Columbia, restricted in the U.S. almost entirely to northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

Even here, its population is sparse. The densest population anywhere is in a very small region of southern Ontario and northern Minnesota, with the Sax-Zim Bog not quite in that area of highest concentration.

Nevertheless, being the most accessible to birders, the Bog is where a lot of birders search for it every June. When one does locate one, the word gets out.

Like Paula’s and my bird last week, and to the frustration of birders who want to see one up close and personal, most of the Connecticut Warblers found in the Bog are “heard-only,” but every now and then, one establishes a territory near a road, path, or boardwalk. My best photos are from 2021, when one sang wonderfully persistently for over a week right along Arkola Road.

I photographed another Bog nester in 2016, in just a bit from Admiral Road.

My only other photographs are from May 2013, when I lucked into seeing a migrant at Park Point—the only one I saw during my Big Year.

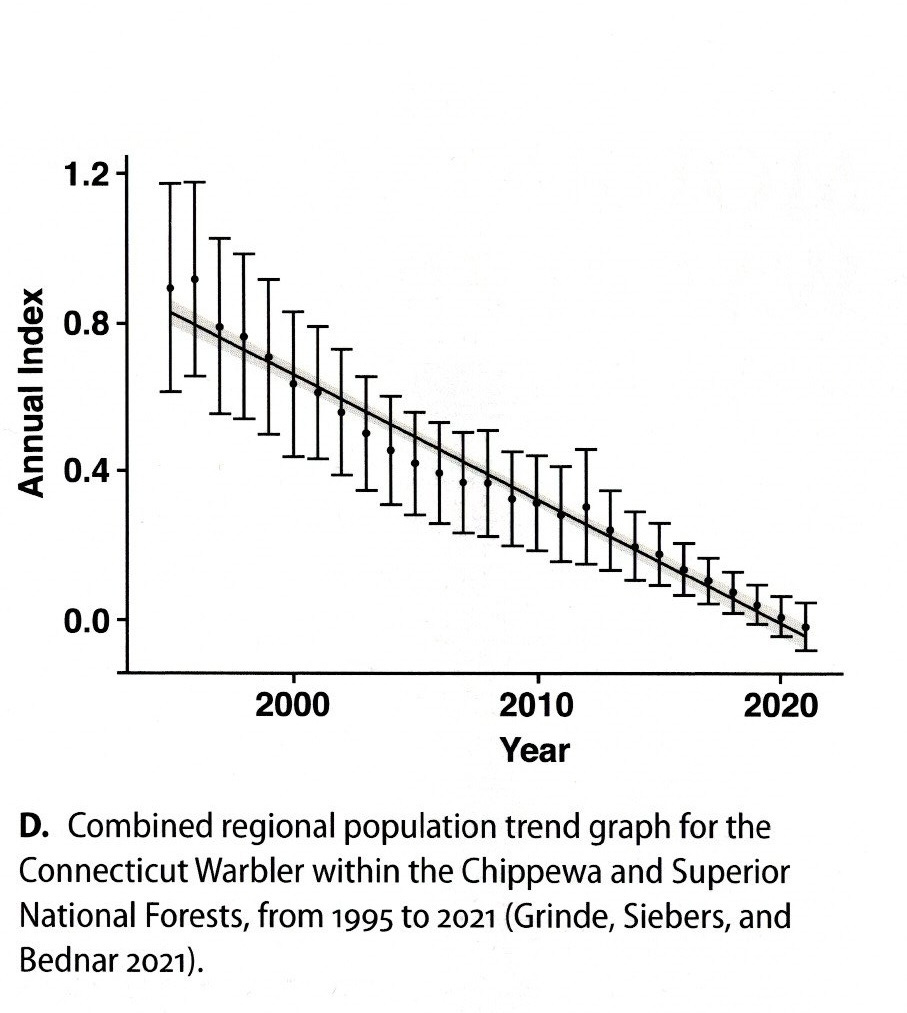

Year after year, Connecticut Warbler numbers get smaller and smaller, a trend that is not leveling off. Northern Minnesota is at the southern edge of the species’ breeding range, and damage to black spruce bogs and tamarack swamps from warming is already manifesting depressingly at the Sax-Zim Bog.

Minnesota’s population within the Chippewa and Superior National Forests has suffered a huge and steady decline from 1995 to 2021.

Michigan’s second Breeding Bird Atlas, conducted from 2002-2008, documented a significant decline in the number of records in the northern reaches of the Lower Peninsula compared to the numbers found during their first atlas twenty years earlier, and noted that there had also been fewer detections in the Upper Peninsula in the second atlas. And the species is in dire trouble in Wisconsin, documented in a 2021 paper in The Passenger Pigeon (Vol. 83, nos.2–3) titled “Status & Trend of the Connecticut Warbler in Wisconsin: Steep Decline Demands Urgent Conservation Action,” by Ryan S. Brady, Richard A. Staffen, Nicholas M. Anich, & Carly N. Lapin.

The federal Breeding Bird Survey shows a significant decline continent-wide.

National Audubon classified the Connecticut Warbler as “climate threatened” after their models predicted that none of the species’ current breeding range would be climate suitable by the year 2080.

When Russ and I were Alaska in 2022, we saw very few caribou; they were only in the areas still covered with permafrost in Denali National Park and Preserve.

As the permafrost melts due to climate change, the habitat there becomes less and less suitable for caribou but appears to be making more habitat for moose.

In the same way, Connecticut Warblers may start finding more suitable habitat further north, shifting their range northward.

Despite their decline, a lot of Connecticut Warblers still remain. Minnesota’s Breeding Bird Atlas data suggest that roughly half a million birds, two orders of magnitude more than the world’s entire population of Kirtland’s Warbler, breed here in the state, the vast majority of them in the Agassiz Lowlands of north-central Minnesota, an area providing habitat for some of the densest populations on the continent. And there are many, many more in Ontario. So why do birders complain about how hard Connecticut Warblers are to see when no one complains about seeing the much, much rarer Kirtland’s Warbler?

Kirtland’s Warbler habitat requires well-drained soil. Even during rainy spells, paths and dirt logging roads into the best habitat are easy to walk. It wasn’t until 1903 that the first Kirtland’s Warbler nest known to science was discovered, but once scientists figured out where to look, it became quite easy to study the species’ nesting habits. Now Kirtland’s Warbler is among the most well-studied of all songbirds.

Connecticut Warblers nest in northern bogs and swamps, very hard to enter by foot. Ornithologists discovered the first Connecticut Warbler nest in 1883, but compounding the inaccessible habitat, the birds are shy skulkers, and even when they’re belting out their loud song, they can be frustratingly hard to find. Only one study of a nesting pair was ever published, in 1961.

When Kirtland’s Warbler was in dire trouble, managers prohibited entrance into nesting areas except on public roads. But those managers knew that birders were both the primary beneficiaries of saving this endangered species and the people most willing to contribute money toward protection and management.

That’s why the US Forest Service, Michigan DNR, and Michigan Audubon started providing free guided walks to see the birds early in the 1970s. Every one of the half-dozen guided hikes I’ve attended, from 1975 through 2019, was filled to capacity.

Now that the species is no longer endangered, maps for self-guided auto tours to the best roadside areas to look for them are available online. And Michigan Audubon and the Forest Service still provide guided tours for a nominal fee, starting from Hartwick Pines State Park and the Mio Ranger Station. It’s an easy drive from Detroit or Lansing to get to the best areas for seeing Kirtland’s Warblers, and even on your own, hiking deep into the habitat along dirt logging roads never feels very remote or dangerous.

The drive to the Sax-Zim Bog from Duluth is an easy 42 miles or so, but once in the Bog, much of the best habitat is along dirt roads which are usually good but can be a little tricky during wet spells, and nowhere are the birds concentrated or common. In recent years, the Friends of the Sax-Zim Bog has been buying up private property in some of the best habitat areas and building boardwalks to protect the fragile bog habitat and make it more accessible. Last year, one Connecticut Warbler did most of his singing right near the Wintergreen boardwalk, but only for a couple of days—I was there the day before the first report and the day after the last report, barely missing that tiny window of opportunity.

The areas of Minnesota and Ontario where the species is most abundant are far more remote, with no major highways and very few roads at all, and mostly out of cellphone range. No wonder few birders even try to add the species to their life lists there.

No matter what, seeing or hearing a Connecticut Warbler anywhere is a matter of the “3 P’s”: Patience, Perseverance, and Providence. But it’s sadly ironic that what is providential for a birder often means misfortune for the birds. Perhaps the luckiest person in the universe with regard to Connecticut Warblers was ornithologist David Wingate, who found 75 of them in one New England spot in September 1987 when the poor birds were grounded by the strong winds from Hurricane Emily.

Seeing or hearing a Connecticut Warbler anywhere is a matter of the “3 P’s”:

Patience, Perseverance, and Providence.

Life is hard for a half-ounce bird that nests only in northern bogs and swamps, winters only in forests in Bolivia and southwestern Brazil, and must travel thousands of miles between them every fall and spring. When Connecticut Warblers arrive on their breeding grounds, they focus on finding the safest places to raise babies, not the easiest spots for birders to see them. Those of us who love this bird take what we can get and thank our lucky stars on the rare occasions when we see or hear them at all.

Thank you. I will use the three p's for this and other nemesis birds. They are infrequent to rare nesters in Pennsylvania. Usually seen sulking under bushes in fall migration, they are considered "Rare. Migrant." in my area in Birds of the Lehigh Valley and Vicinity (2014). They here are also found in brushy areas, overgrown fields, and forest edges. They can be confused with Mourning and Hooded Warblers, Common Yellowthroats, and even Yellow-breasted Chats if seen at a glance scurrying underbrush, so if you think you saw one of these, maybe it was a Connecticut unless you heard it!

Talk about lucking out, I was in downtown Allentown one morning looking at birds hawking insects in the floodlights of a skyscraper from a cemetery. At dawn, down came a Summer Tanager, a Black-and-White Warbler, and a Canada Warbler chasing insects and each other around!!