(Listen to the radio version here.)

From the very first day I became a birder, March 2, 1975, I’ve loved the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, my Gold Standard as a resource for every birder, beginner as well as advanced. That first day, I found the bird that would become #1 on my life list—a chickadee—but which one?

I was in southern Michigan, in the range of the Black-capped Chickadee according to my Golden Guide’s range map, but the Carolina Chickadee’s range didn’t appear to be much further south and the field guide said that the ranges overlapped a bit in winter. There was still plenty of snow on the ground, and as a rank beginner, I didn’t grok that in winter, it would be the Black-capped Chickadees settling a wee bit south of their range, not Carolina Chickadees moving a bit north of theirs. I knew my chickadee was probably a Black-capped, but wanted to be 100 percent certain.

The guide said the Black-capped Chickadee had “white feather edges on wings,” which I could sort of see, but the illustration for the Carolina Chickadee was from the front, not side, and the feather edges appeared pale enough that I wasn’t certain my bird was one and not the other. The other field marks were written as comparisons. The Black-capped Chickadee had “rustier sides” and “whiter cheek patches.” The Carolina Chickadee had a “smaller bib” and “shorter tail.” Wouldn’t I need to see both of them to make any of those judgments?

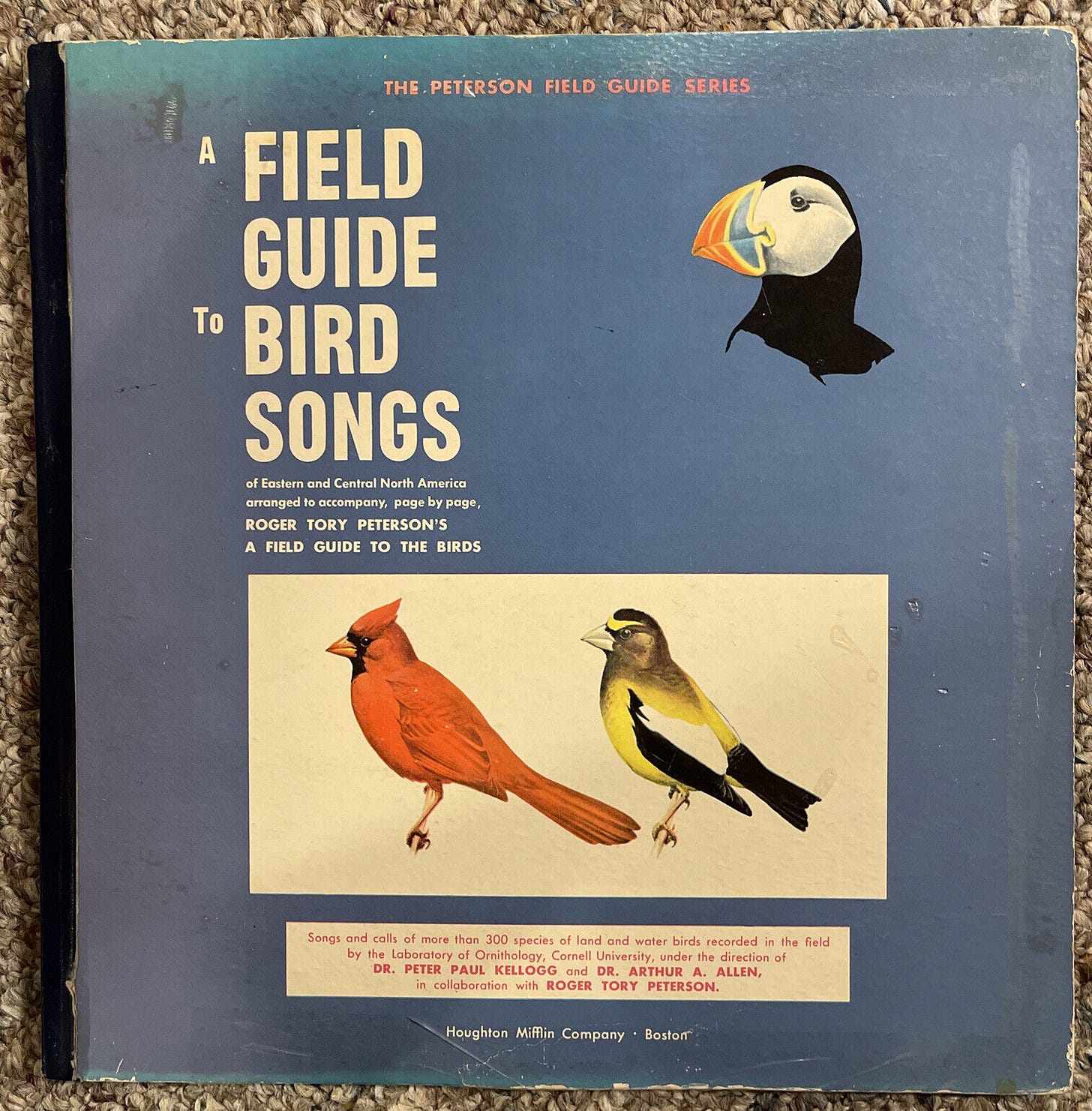

My bird didn’t whistle but did make a lot of dee-dee-dee calls. According to the field guide’s Carolina Chickadee description, “Calls are faster than corresponding calls of the Black-capped.” I’d read both the Golden and Peterson guides cover to cover, and both mentioned recordings by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Maybe I could listen to one of those to clinch the ID. So the moment the bird flitted off, I raced to my car and headed straight for the Michigan State University library’s media center.

The chickadee entries in the 2-disk record album from the Peterson field guide series did the trick. Yep—my bird had sounded exactly like the Black-capped, not the Carolina Chickadee. After that, I spent so many evenings in that media center, usually listening to that specific album, that Russ bought me my own copy for Christmas. It included songs and calls of birds from the eastern half of the continent, including the incredibly rare, now extinct, Ivory-billed Woodpecker and Bachman’s Warbler. I’d listen to it when I was folding laundry and ironing, which helped me identify birds in the field much more quickly. I took two trips out west in 1979, and Russ bought me the 3-record Western edition ahead of time. One day, when I heard an unfamiliar bird singing, my brain instantly heard a familiar nasal voice saying, “Page [something or other—44 years later, I can’t remember the number], MacGillivray’s Warbler.” And when I searched through the foliage, sure enough—there it was!

When I started producing For the Birds in 1986, I used those records, and soon added the second edition of the Peterson album, to mix in the sounds of the species I was talking about. It didn’t occur to me for a couple of years that I really should have asked the Cornell Lab for permission. I immediately wrote to the director, Charles Walcott, confessing my copyright violation and asking what I should do moving forward. I mentioned that I produced the program as an unpaid volunteer and included a tape of several programs I’d done, including my 1987 April Fools program, a silly concoction about how the “Cornell Lavatory of Orthinology” had “cracked the code of all bird language.”

Dr. Walcott wrote back, granting me permission to keep using the Lab’s recordings, and mentioned that the Lab itself was considering producing radio segments as public outreach. I learned later that he’d gotten a huge kick out of the April Fools program in particular, pulling people into his office to listen to it.

So I can affirm that from Day 1 of both my birding life and my radio production life, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology has been my most important, and beloved, ornithological resource. At the time, I could never have imagined that I’d ever have multiple reasons to love them even more. That’s a story for next time.