(Listen to the radio version here.

On January 2, 1979, Russ and I were birding on some country roads outside Aransas, Texas. Well, I was birding—Russ was obligingly driving our Ford Pinto and trying to keep track of where we were in an area where none of the farm roads seemed to be marked and the sky was too overcast for us to even guess where the sun might be.

I’m a useless navigator—my dyslexia makes maps, and even straightforward directions saying when to turn left or right, bewildering. In those days before GPS, I got lost a lot, and the funny thing was, virtually every time I got lost, I found at least one cool bird before finding my way back. So getting lost has never felt like a bad thing to me.

Russ isn’t nearly as laid back when he doesn’t know where he is, and to top that off, he suddenly noticed that our gas gauge was reading EMPTY. Right as he was starting to panic, I saw a group of Turkey Vultures on the ground in one of the farm fields, except three of them had oversized heads, black-crowned with lots of whitish feathers on the neck, upper chest, and upper back. I could feel my heart racing as I pulled up my binoculars and let out a whoop—they were caracaras!!!

The Crested Caracara, a tropical falcon nicknamed the Mexican eagle, is a striking outlier in the falcon family, feeding on carrion and small animals on the ground rather than chasing prey in flight. The bare orange skin on the face, unlike any other falcon’s, calls to mind a vulture’s bare head, designed for plunging into carrion without getting feathers gooped up, and caracara wings are broader and more rounded than other falcons, allowing them to soar with vultures.

I’ve been lucky enough to see these striking birds in Cuba, Costa Rica, Panama, and Peru as well as, appropriately, Mexico, where they’re the national bird.

I find it amusing that North Americans seem so drawn to charismatic carrion eaters—Canada’s handsome national bird, the Canada Jay, capitalizes on carrion during long cold winters.

Our own national bird, the Bald Eagle, spends an inordinate amount of time flying over highways searching for roadkill.

The United States has only these two neighboring countries, so you’d think we Americans could keep track of their national birds, but many people have never heard of caracaras. The New York Times “Spelling Bee” puzzle doesn’t accept caracara as a word, and every time I type caracara in a text message, spellcheck changes it to Caracas. That drives me nuts, but at least Venezuela is within the bird’s geographic range.

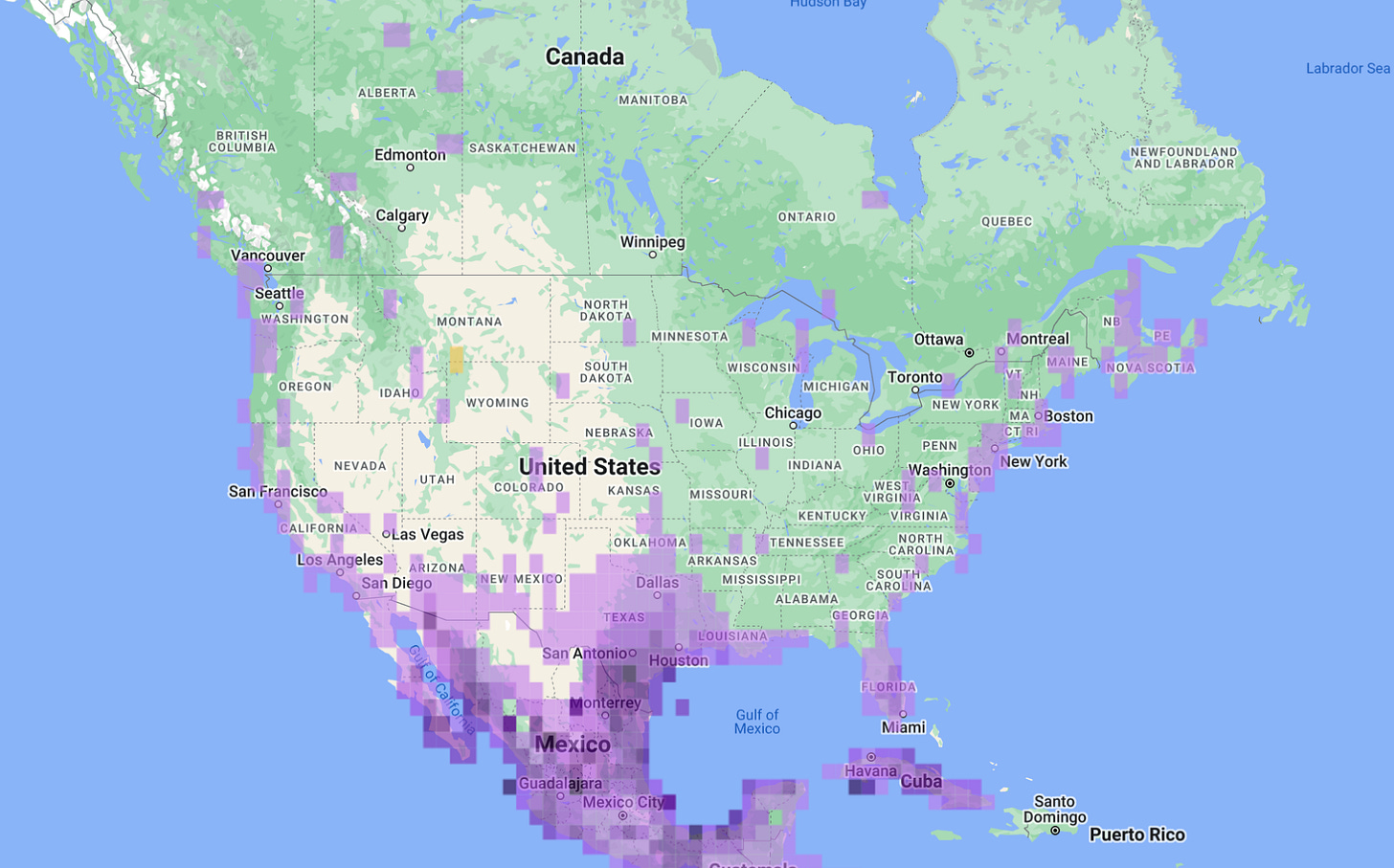

No border wall could keep Crested Caracaras out of the United States—their range extends well into Texas and Florida. Back in the 70s, I was utterly taken with how handsome and yet funky looking they were, and I badly wanted to see one on that first trip to Texas. Despite our almost empty gas tank and not knowing where we were, Russ was gracious enough to stop for a minute or two before anxiety won out, so I got satisfying, if brief, looks at this dreamed-about lifer.

It didn’t take long for us to find our way to marked roads and a gas station. Russ was relieved, but I can’t say I was—I knew we’d eventually figure out where we were and get gas. For me, the experience was unadulterated pleasure. All’s well that ends well.

I hope all ends just as well when caracaras find themselves lost—the species seems to have a worse track record than I do as far as that goes. Vagrant Crested Caracaras have wandered here and there all the way along both the East and West Coasts into Canada, and have also appeared in quite a few inland states and provinces.

In May 2014, one found its way to Door County, Wisconsin, and just last week one was sighted even further north in Wisconsin, up in Ashland County not far from Marengo. I of course wanted to see it but couldn’t get away until Saturday morning. The weather forecast called for rain ending by 9 am, so I left home about 8:30, arriving at the hotspot at 10:20 or so.

The bird had been seen consistently since Tuesday on a narrow stretch of farm road called “Section Five Road” that runs to the north and south of Highway C.

The stretch north of C runs past a cow pasture and a farm field; the southern part past a beautiful wooded area to the east and a farm field to the west. Most of the photos I’d seen of this caracara showed it in a big dead tree in front of the woods, but it had also been seen in the farmed stretch north of C. It obviously had to fly from one place to the other, and during a rain, it could have been anywhere. My strategy was to slowly drive up and down Section Five Road, stopping frequently to scrutinize everything I could. Several other birders were doing pretty much the same thing.

But the thickly overcast sky must not have consulted the official forecast. It was still raining steadily when I arrived and didn’t let up for almost two hours—sometimes pouring, sometimes drizzling heavily, but always raining. A group of Bald Eagles were hunkered down in some trees in the pasture north of C.

One raven, perched on a distant snag, managed, in the foggy drizzle, to trick some optimistic birders into thinking it was the caracara.

As the rain finally eased up into a very light drizzle about 12:15, suddenly the eagles and ravens started moving about. That’s when I headed back to the south side of Section Five Road. Just as I crossed Highway C, there was the caracara, flying out from somewhere in the middle of the dense woods to the snag where so many people had photographed it. I of course started clicking away.

If the caracara had been a person, I’d have assumed it was unhappy about the soaking—we birders sure were! But it’s trickier to understand how birds feel about normal natural phenomena they deal with all the time. Whatever it was thinking and feeling, it was sopping wet and spent the entire time I was watching and photographing it shaking out its wet feathers, preening, and staying put in full view of me and the equally persistent birders in the only other vehicle that was still there.

After a few minutes, I moved a bit further down the road so I could place it against a nicer background. The rain hadn’t entirely stopped yet—it would dissipate for a minute or two and then start up again.

I’d have loved to stay longer to photograph it after its feathers were dry, maybe even capturing photos of it in flight or hunting, but I’d promised to be home by early afternoon; when I looked at my watch, it was already quarter to one. That was fine—I’d never photographed a soaking wet caracara before, so I was happy with what I got.

I was thrilled to see this tropical bird so far out of its range, but worried about it, too. A handful of unusual vagrants have returned year after year to a place where they don’t belong, but that’s bizarrely exceptional and hasn’t happened with out-of-range caracaras. Unless something horrible happens to this one and someone finds its tragic remains, we’ll never know what happened to it after it finally disappears.

I’d like to think that this bird is like me—that it’ll make wonderful discoveries while it’s lost but then find its way home again. Hope is the thing with feathers and, wet or dry, caracaras have plenty of those.