Discovery Cove

We can learn a lot about wildlife in theme parks and zoos, but I wish they taught more about how and where these animals survive in the wild.

(Listen to the radio version here.)

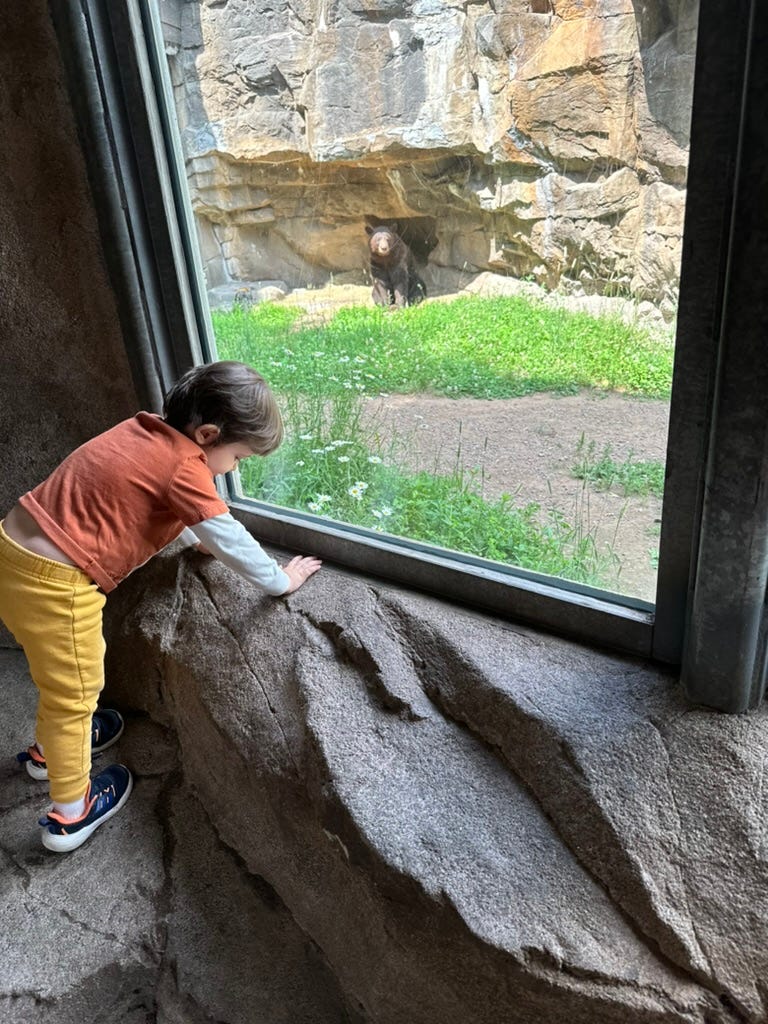

I’ve taken my grandchild Walter to the Lake Superior Zoo a few times, and I’m delighted that even though he’s not quite three years old, he already knows important things about animals that I didn’t learn until college.

Throughout my childhood, I thought there were essentially five kinds of animals: pets like my family’s dog and cat and my Grandpa’s canaries; animals we could see in our everyday life that weren’t pets, such as squirrels, pigeons, robins, and sparrows; farm animals such as cows, horses, chickens, and turkeys; animals in zoos such as lions, bears, zebras, penguins, and ostriches; and animals on TV shows like Wild Kingdom. I had no clue that virtually all the animals featured in zoos and on Wild Kingdom were species that lived and moved about freely in places where other little girls could see them in their everyday lives, or that pets and farm animals were descendants of genuinely wild species from somewhere on this planet.

Walter already knows that bears live wild right here in Duluth, sometimes even visiting his own backyard; that zoo animals live in places he can go to—he’s already seen wild prairie dogs in the Badlands in South Dakota; and that the Duluth zoo’s Turkey Vulture is the exact same kind of bird we see flying overhead on some of our walks. He hasn’t seen Wild Turkeys yet, but his grandmother in New York raises chickens in her backyard, and next year we’re all going to Hawaii; Red Junglefowl released on Kawaii long ago have become established as countable wild birds there. Junglefowl are native to South and Southeast Asia but have been domesticated for so many centuries that in most places, recent and continuing escapees muddy the question of how truly wild they are. Those running about in Key West, Florida, aren’t yet countable, but I’ve been told that some DNA studies indicate that they’re much more closely related to breeds of chickens in Spain than those here in the United States, suggesting that they are truly wild descendants of birds brought here by the Spanish conquistadors.

When I visited Kissimmee, Florida, our group spent April 14 visiting two places where the focus was captive animals, which of course aren’t countable on birding lists but are nevertheless interesting for most of us birders. In the morning, we went to Discovery Cove, a limited-admission SeaWorld property focused primarily on marine animals but with a walk-in aviary and opportunities for close-up interactions with American Flamingos.

Discovery Cove highlighted some of my favorite elements of zoos and captive animal programs, but also my biggest pet peeve. The captive flamingos were clearly well cared for, and my grandson Walter would have thoroughly enjoyed seeing the morning flamingo parade, when the birds are walked from their nighttime roosting area to their daytime display area. This parade is roped off but allows such close views that I got some of my best closeup photos ever. There’s an even more immersive “flamingo mingle,” but children visiting that must be at least six years old.

Plenty of friendly staff were close by during the flamingo parade, sharing their knowledge about flamingo care and how the individual birds interact with humans and one another, but like virtually every zoo I’ve ever visited, the staff were not very knowledgeable about flamingos as wild birds. They emphasized the individual birds, which is important, but neglected to tell us how these animals live outside the sheltered life of captivity or where in the world they can be found in the wild, including Florida.

Discovery Cove called their flamingos “Caribbean Flamingos” as does the Discovery Cove and SeaWorld website, though their English name is officially “American Flamingo,” in part because their range extends beyond the Caribbean down to the Galápagos. As far back as the 1830s, Audubon called the species the American Flamingo, now such a well-established name for the species that if you type “Caribbean Flamingo” on Wikipedia, it takes you to the American Flamingo entry.

The Discovery Cove website said this species is “found throughout the Caribbean (Cuba, the Bahamas, the Yucatan, Turks and Caicos), the Galapagos Islands, and the northern part of coastal South America,” but nowhere mentions that its range includes south Florida; that many years one or more still turn up in the Everglades; nor that for the past few years, a perfectly wild American Flamingo has been living in the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge in the Florida panhandle. This would be understandable if Discovery Cove was in any other state, but somehow missing this important information in the very state flamingos are so associated with seems to be throwing away an important educational opportunity.

The “Explorer’s Aviary” at Discovery Cove had lots of cool birds on display, an opportunity to hand-feed some of them, and cards to help identify them. Again, Walter would have loved that, but visitors could easily come away without a clue how or where these birds live in the wild.

In the aviary, one staff member was holding a wonderfully cooperative Tawny Frogmouth, an Australian species once classified with potoos, nighthawks, and whip-poor-wills. She even managed to coax the bird into opening its capacious mouth, at least momentarily, though I didn’t get a photo of that. I may have missed her mentioning that the bird ranges in the wild only in Australia and Tasmania. I’ve seen museum specimens but had never before seen a living frogmouth and will probably never see one in the wild, so I relished the photo op.

After we left the aviary, we came upon another staff member holding an Eastern Screech-Owl. She was taking questions, and after my prompting, she explained to the group that this species lives in the wild right there in Florida, which surprised some of the people around me.

As in just about every theme park in the Orlando area, we also saw plenty of perfectly wild birds at Discovery Cove. I so wish Disney World, SeaWorld, Discovery Cove, and other places like this displayed signage showing some of these conspicuous wild residents of Central Florida, from grackles, sparrows, and cardinals to egrets, herons, and cormorants. In an open area where dolphins, rays, sharks, and other marine species were on display, I overheard one middle-school-aged child ask his parents why a Snowy Egret sitting on a post didn’t fly away. They said its wings must be clipped, not realizing that these large, charismatic birds are wild and free throughout central Florida.

Discovery Cove did an excellent job of providing magical encounters with fascinating animals, and it’s the job of schools, not theme parks, to educate the American public about local wildlife. But I sure wish zoos and theme parks with an educational mission could step up their game a bit.