(Listen to the radio version here.)

I’ve been trying to teach my 2 ½ year-old grandson Walter about the seasons. We tell little children, and sometimes even ourselves, that every year is made up of four of them, each lasting one quarter of the year, but that’s about as honest as telling them that there’s an Easter bunny and a tooth fairy. Indeed, brightly colored Easter eggs in a pretty basket or a quarter under a pillow are way more substantial proof of those childhood stories than anything we could drum up to prove that spring really does begin on March 20 even as snow in the backyard grows deeper and white-tailed deer grow thinner.

In Duluth it usually snows at least a few times in April, and sometimes in May, and we’re not supposed to set out tomato plants without protection until Memorial Day, but no matter what is happening weather-wise, when robins start to sing, it’s spring.

Robin movements are tied to the 37-degree isotherm, so the first earthworms are sure to be stirring even as old berries and crabapples are still available for emergency meals.

And robin song seems to give the go-ahead to lots of other birds. This weekend, right after I heard my first robin songs of the year, I saw my first grackles, Fox and Song Sparrows, Golden- and Ruby-crowned Kinglets, Brown Creepers, Hermit Thrushes, and Yellow-rumped Warblers.

I also missed my first woodcock of the year—my birding friend Bruce Munson, who happens to be my daughter’s next-door neighbor, saw one in his backyard Saturday and tried to stay on it till I got there, but crows chased it away.

I took a short walk in their neighborhood searching. I didn’t find Bruce’s woodcock but did luck into a small flock of Bohemian Waxwings and a few robins, the last of winter and the first of spring feasting together on mountain ash berries.

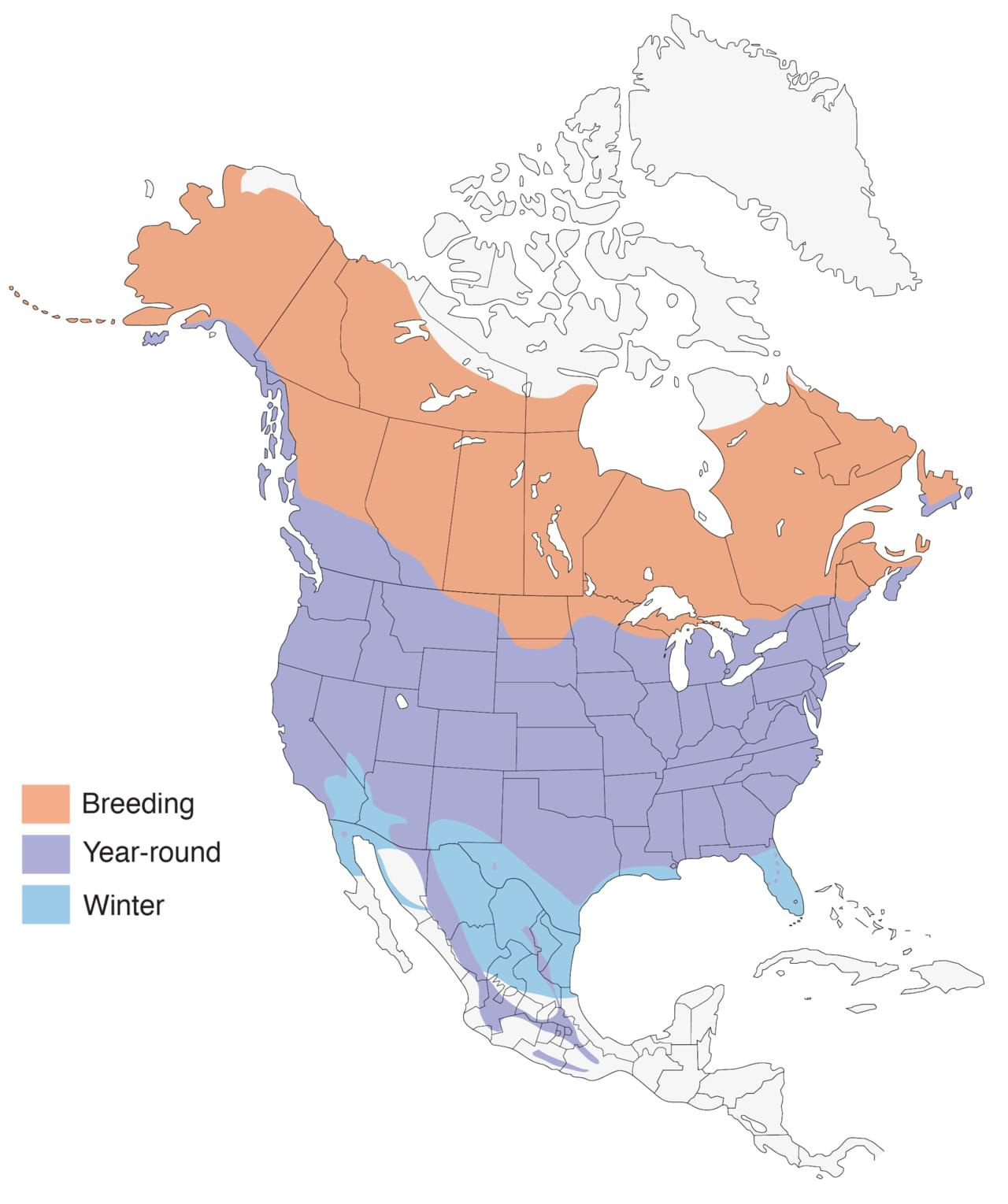

Using the robin as a sign of spring in North America is far more universal than crows carrying sticks, Bald Eagles grasping talons, or bluebirds returning to their nest boxes, almost certainly because robins are both widespread and homey, found in wilderness, rural areas, and the hearts of big cities. And their switch from winter behavior to singing on territory is so welcome, their songs within the hearing range of most of us. I can hear them very well without my hearing aids, though they sound even prettier when I wear them, the high-frequency overtones lending a brilliance to the rich caroling.

And because robins are backyard birds for so many of us, they figure in our daily lives in ways most birds can’t. I have childhood memories of watching them on our lawn and skipping to school to their music. My first summer of birding, when I pulled an all-nighter writing a term paper for field ornithology, a robin kept me company the entire night, singing outside our apartment window. A pair of robins nested right outside my son Tom’s window when he was little; his delight in discovering and watching them each day filled me with joy. During the height of the pandemic when I was rooted to home, the robins singing in my backyard gave me a great deal of pleasure, and the recordings I made were a gift that keeps on giving.

But the robin who touched my soul most deeply was my first robin of 2014 and my little dog Photon’s last. Photon had accompanied me birding her entire life, always paying close attention to birds when we were out together. She had been failing rapidly in the weeks before her 16th birthday that Friday, April 4. Then over the weekend she had a couple of seizures and slept almost all the time. I made an appointment for our vet to come to the house at 11:30 Monday, April 7.

Photon slept most of the morning, but about 11 o'clock, she unsteadily made her way to the back door. I let her out and stood on the porch with her. A robin was singing away—the very first robin song I'd heard that year—and she sat down on the porch and turned her face to listen to him. A chickadee sang in another direction, and she turned her face toward him, and then tracked a crow cawing as it flew over. Then she turned to the robin again, listening intently for a lovely yet heartbreaking ten minutes. When he stopped singing, she pulled herself up on weak legs and walked to the door.

She made her way to a comfortable spot and settled down, nestled against me. I’d turned on a recording I’d made with her in northern Wisconsin, of early-morning birds including robins, and she didn’t stir when Dr. Hargrove arrived. It was time, and her spirit rose ever so softly and gently, and slipped away.

Nine years later, I still can’t hear April robins without thinking of Photon. Robins are proof that spring has returned, and ever so much more.

So beautiful. Thank you. In Spanish, "primavera" means both "spring" and "robin."