Generational Amnesia

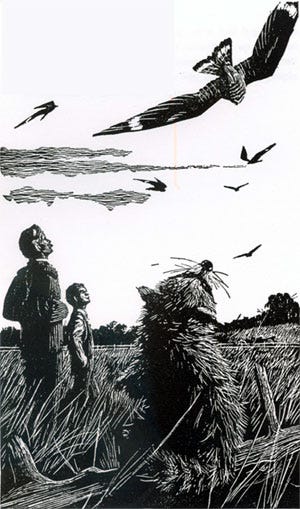

Every generation thinks the wildlife numbers they're experiencing now are what is "normal."

(Listen to the radio version here.)

Last week, The Washington Post published a column by Michael J. Cohen, their Climate Advice Columnist, titled “Why you should tell your children about vanishing fireflies”. He wrote about spending time in a remote area of Maine: “To my eye, this is as Edenic as you get in America today,” but then noted how Maine is one of our most logged states and how cougars, caribou, and gray wolves have been extirpated from the state. The sea mink, a larger, redder relative of the American mink once found along Maine’s coastline, became extinct in the late 19th or early 20th century.

Changes over past decades are not evident to anyone exploring an area for the first time. Cohen writes: “Changes here unfolded over centuries. Each generation came to see the woods and rivers around them as normal even as the ecosystem degraded. There’s a name for this: shifting baselines”

Cohen explains that the term shifting baselines was coined by marine biologist Daniel Pauly, who wrote a 1995 note in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution, documenting how fishery scientists generally consider the size of fish populations at the start of their careers as the normal that they set as a goal for management. As each new generation enters the field, the fish stocks at that point become the new normal, and there is “a gradual accommodation of the creeping disappearance of resource species.”

In last week’s Washington Post column, Cohen writes:

Shifting baselines is now shorthand for generational amnesia of the natural world. As species decline or die off, our cultural memory of them fades. We might remember the abundance and diversity of our childhood but never imagine the world of our grandparents — or of their ancestors. This phenomenon has already been documented among groups as diverse as bush meat hunters in Africa and birders in Britain.

Cohen suggests that we tell stories about our own childhood experiences to make sure this generation realizes that lightning bugs really did used to be much more abundant. Something significant has been lost.

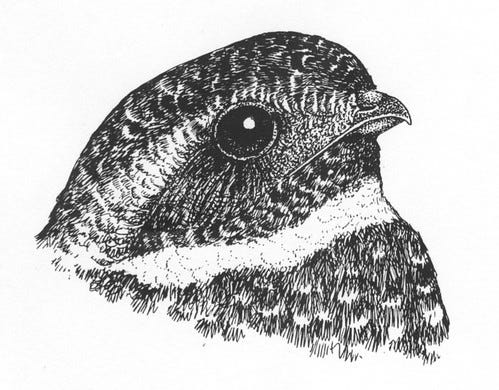

Last week I wrote about how the people counting nighthawks in Duluth started their count in 2008. When asked in 2019 about the steep decline in nighthawks over the past half century noted by Partners in Flight, researchers in Canada, and several state departments of natural resources, one young counter said, “We’re not seeing that at all. We’re actually seeing an increase in our counts in the last 11 years.” As Cohen’s recent column and Pauly’s 1995 journal note suggest, that’s a clear and understandable example of what Cohen calls “generational amnesia.”

But I’m afraid the problem is even more insidious and intractable than that, making it extremely hard for both older, established scientists and young, cutting-edge researchers to see the whole picture. Without integrating all kinds of information, including a wide array of different scientific methods for assessing each species’ abundance and, yes, anecdotal accounts by competent observers from the past, it’s impossible to get a clear picture today of what had once been long-term sustainable numbers. I’ll explain why next time.