Getting away with murder, Part 3

My visit to a rehab center after the BP spill

(Listen to the radio version here.)

While I was in Louisiana in late July and early August 2010, I saw with my own eyes that a lot of oil had reached beaches and small vegetation islands in Barataria Bay, and that birds badly crippled by oil were not getting to any rehab centers if they could open their wings and try to fly, even if they just fell in the water. I was there for less than two weeks, but I talked to Drew Wheelan after reading all his first-hand observations in the American Birding Association’s blog. (I don’t know if or where these posts have been archived—I can’t find them online anymore.) Drew arrived in May, mostly slept in his truck, and stuck it out for months except when he developed pneumonia and had to leave for a short time.

I had joined the American Birding Association back in the early 80s, but as I started allocating my limited money to organizations focused on conservation and research, I quit the ABA, which seemed focused on birding only as a hobby. But by the time I got to the Gulf in late July, the ABA was the ONLY bird or conservation group posting firsthand accounts that were at all consistent with what I was seeing. After meeting and talking to Drew, I of course rejoined.

I had obligations at home but couldn’t bear to leave the Gulf until I visited at least one rehab center treating oiled birds. The public and media were prohibited from visiting any of the four rehab facilities except during rare, scheduled media events, so I stuck around for the August 5 public information session at the Theodore Oiled Wildlife Rehabilitation Center near Mobile.

In just the few days I’d been out in the field and the relatively small area I’d been to, I’d seen several badly oiled birds, a few that would have been extremely easy for any experienced rehabber or bird bander to capture to get to a rehab center—if only trained volunteers and experienced rehabbers had been allowed to capture oiled birds, as had been allowed in previous oil spills.

BP insisted that both live and dead birds were “legal evidence,” meaning an appropriate chain of custody (authorized by BP, of course) needed to be maintained. (Based on this 2017 NOAA post, this is now the protocol in all oil spills. I don’t know if at other oil spills birds like the badly-oiled Black-crowned Night-Heron would be considered “flighted” and prohibited from being rescued.)

The rehabbers at the center were excellent, but none had been out in the field to see what I’d seen—they were only allowed to treat birds brought to them by BP’s approved people because of that “chain of evidence” requirement.

None of the local wildlife rehab centers in the Gulf States was authorized to treat the birds oiled during the BP spill. The four centers that were allowed to accept oiled birds were temporary facilities set up and operated by the International Bird Rescue Research Center. This California-based organization has become a world authority on treating oiled wildlife, so once oiled creatures were brought here, they truly were in good hands.

Based on my actually seeing oiled egrets, herons, pelicans, gulls, and shorebirds, I expected that these four centers would each be treating dozens or even hundreds of birds, but no—the only birds the Theodore Oiled Wildlife Rehabilitation Center was treating at the time I was there were two immature Northern Gannets.

Gannets are true oceanic birds, coming to shore only to nest on rocky cliffs. Once the babies leave, they never return to land until they are four or five years old. They quickly learn to plunge-dive for fish out where water is deep…

… and rest only out on the water.

When I’ve seen them from shore along the East Coast, they’ve just about always been too far out to get satisfying looks with just binoculars. I got my best looks and photos when I was on a pelagic trip in January 2013, our boat far from shore. Many or most of the gannets killed by oil in the Gulf would have been too far out to wash ashore, especially in the early days of the spill when BP was burning surface oil along with any debris.

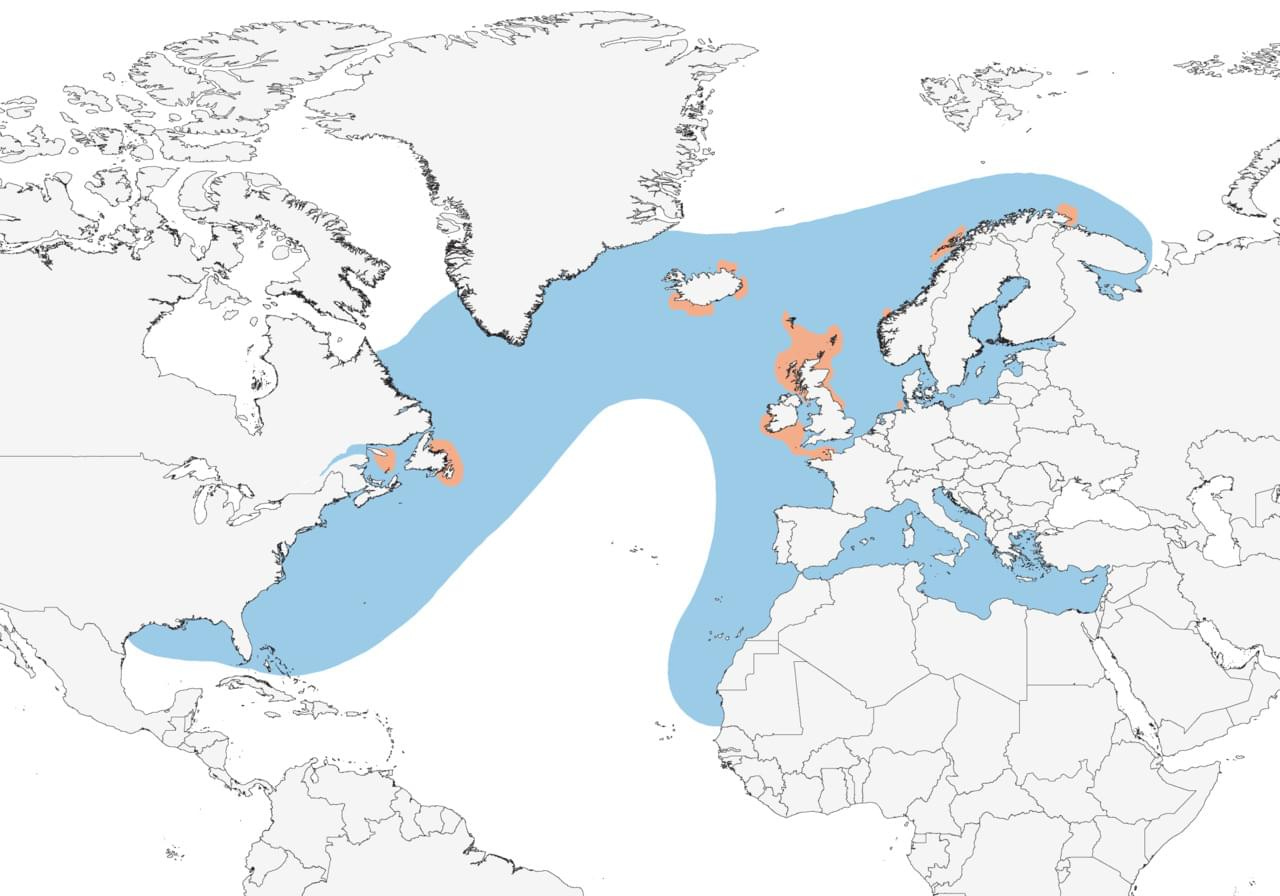

Gannets nest in huge colonies in the north Atlantic along the Canadian coast, Iceland, and northern Europe, and winter along the Eastern Seaboard, with some getting as far as the Gulf of Mexico. By February, adults head north, and even most subadults have left the Gulf by March.

At the time of the Deepwater Horizon explosion on April 20, virtually the only gannets remaining in the Gulf had to be ones that had hatched the previous summer, so of course the two gannets being treated at the rehab center were immatures. Indeed, the rehabber noted that none of the gannets they’d treated from the start were adults.

One of the reporters asked why they were finding only immatures. Licensed rehabbers have extensive training in physiology and veterinary issues but often aren’t very knowledgeable about natural history, especially about animals they seldom encounter, and these rehabbers were from California, far out of the range of Northern Gannets. So the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service spokesman answered this one. He said as far as they could tell, adult gannets had enough experience to successfully avoid what little oil there was in the Gulf. Neither he nor the rehabber speaking to us realized that adult gannets simply aren’t in the Gulf by mid-April. When reporters were chatting with him after the presentation, someone asked about his background. He said he worked on deer research and management.

There are many experts specifically knowledgeable about the birds in the Gulf in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and a lot of universities and non-profit organizations. Was it possible that BP had specifically selected spokespeople who were sincere, well-meaning experts in their own fields who were not likely to be very knowledgeable about the wildlife that would be most affected by this spill?

The news reporters went away satisfied that just as they’d heard, there really weren’t many birds or other animals affected by the largest oil spill ever. Between burning, dispersants, and evaporation, all that oil really had been miraculously Raptured up, up and away. Nothing to see here, folks.

Very much like the trump administration. Nothing but lies and misdirection. Disgusting.

I have been meaning to read all parts of this series with much intent, and will. Sorry you, them, and the birds had to experience such trauma. And the feelings simply do not go away, though the pain may subside a little after a while. I am still shocked. Kudos to you for bringing this back to our attention, and so many conservation issues WE SIMPLY CANNOT AND SHOULD NOT FORGET.