Hoarding

Stashing away more than you need is not always greedy, at least if you're a jay or a chipmunk.

(Listen to the radio version here.)

For many years, I lived with a Blue Jay named Sneakers (a bird I was allowed to “possess” with state and federal education permits) and, during part of that time, a friendly squirrel named Chuckie who I’d raised as an orphaned baby. Sneakers was restricted to the house, but Chuckie came and went as she pleased. We could tell when she was nursing babies somewhere because—well, it was obvious—but she never brought her babies to our house, apparently preferring to keep her professional life separate.

Anyway, from the time she was a chick, Sneakers was fascinated by my kids’ Legos, especially the tiny, round, bright red or yellow Lego vehicle headlights.

If the big Lego drawer in the living room was open, she’d fly into it and pull out, one by one, several of those tiny blocks, tucking them all in her gular pouch—the expandable storage pouch in a Blue Jay’s throat.

After filling her gular pouch with Legos, Sneakers would fly to the top of our draperies and tuck each one in the fold of a pleat, or to our sofa to push them into spaces between the cushions. She also stuck them in the carpet. When a scrap of paper was available, she’d cover those the way jays cover an acorn cached on the ground with a leaf. For this very purpose, I set a small pile of scrap paper on an end table to help me find all the Legos before vacuuming.

In nature, a jay’s gular pouch holds food items to cache, and Sneakers could do that, too, with peanuts, sunflower seeds, and acorns. (We don’t have any oak trees in my neighborhood, but my beloved neighbor Mary Tonkin would bring us a bucket or two whenever she visited relatives in Crystal Lake near Mankato.)

We had a living room chair with tufted upholstery—with Sneakers around, a peanut or an acorn from Mary was invariably wedged into each indentation.

Chuckie the squirrel was not into Legos, but when she came by, she’d search for some of Sneaker’s hidden food treats. Some she’d eat right then and there; others she carried to new spots to cache. When Sneakers was watching, she’d quickly dig those up to cache somewhere else. It was endlessly fun watching them.

At my outside bird feeders, I quickly learned to distinguish my neighborhood Blue Jays from those just passing through. The local ones might eat one or two sunflower seeds in the feeder, but then they’d stuff their gular pouch and fly off, mostly using the feeder as a grocery store. Those migrating through had no reason to store food here—they used the feeder as a sit-down restaurant.

Lately I’ve been watching the Peabody Street Blue Jay family. When they fly in, they might visit the birdbath…

… pig out in Russ’s cherry tree and my juneberries…

… sit in a bird feeder to eat, or carry off one peanut or a pouch-full of sunflower seeds. I love how Blue Jays make provisions for an unknown future even as they savor today.

But watching them rekindles how angry I felt reading a book last year (Slow Birding, by Joan E. Strassmann) with a chapter about Blue Jays. The author wrote, “The jays are smart enough to cache and smart enough to find most of their acorns but not quite smart enough to find all of them.” Not one study has ever suggested that the food jays don’t retrieve is evidence of a lesser intelligence or that they forgot where they left it. When food is abundant, they always tuck away far more than they’ll probably need, just in case. If one jay loses its caches, other jays are fine with it raiding theirs.

In addition to my backyard jays, lately I’ve been watching someone else carrying off sunflower seeds and peanuts. My son Joe was here from Florida over the Fourth and started feeding a couple of chipmunks by hand on our patio. One became shockingly tame. I’m calling her Dizzy because her cheeks are so adorably expandable—I can imagine her blowing into a tiny trumpet.

Dizzy sometimes sits in my lap or on my hand or shoulder, and when she hops into a bucket of sunflower seeds or peanuts on our patio table, she lets me pet her as she stuffs her cheeks. I know she’s a female because she even let me pick up her back end to check.

When her cheeks are filled to capacity, Dizzy grabs a final peanut in her teeth and runs off to her burrow, which seems to be a couple of houses away. It's surprising how much food she’s been packing away, especially because she’s a slender little thing.

The word “hoard” has negative connotations. Merriam-Webster’s defines the noun as:

a collection or accumulation or amassment of something usually of special value or utility that is put aside for preservation of safekeeping or future use often in a greedy or miserly or otherwise unreasonable manner.

Just about everyone who’s watched Dizzy stuff her cheeks, after they stop laughing, seems to use the word “greedy” or “piggish,” but I just remind them about how many of us stuffed shopping carts with toilet paper four years ago. When we don’t know what the future holds, it’s better to pack away more of what we may need than less.

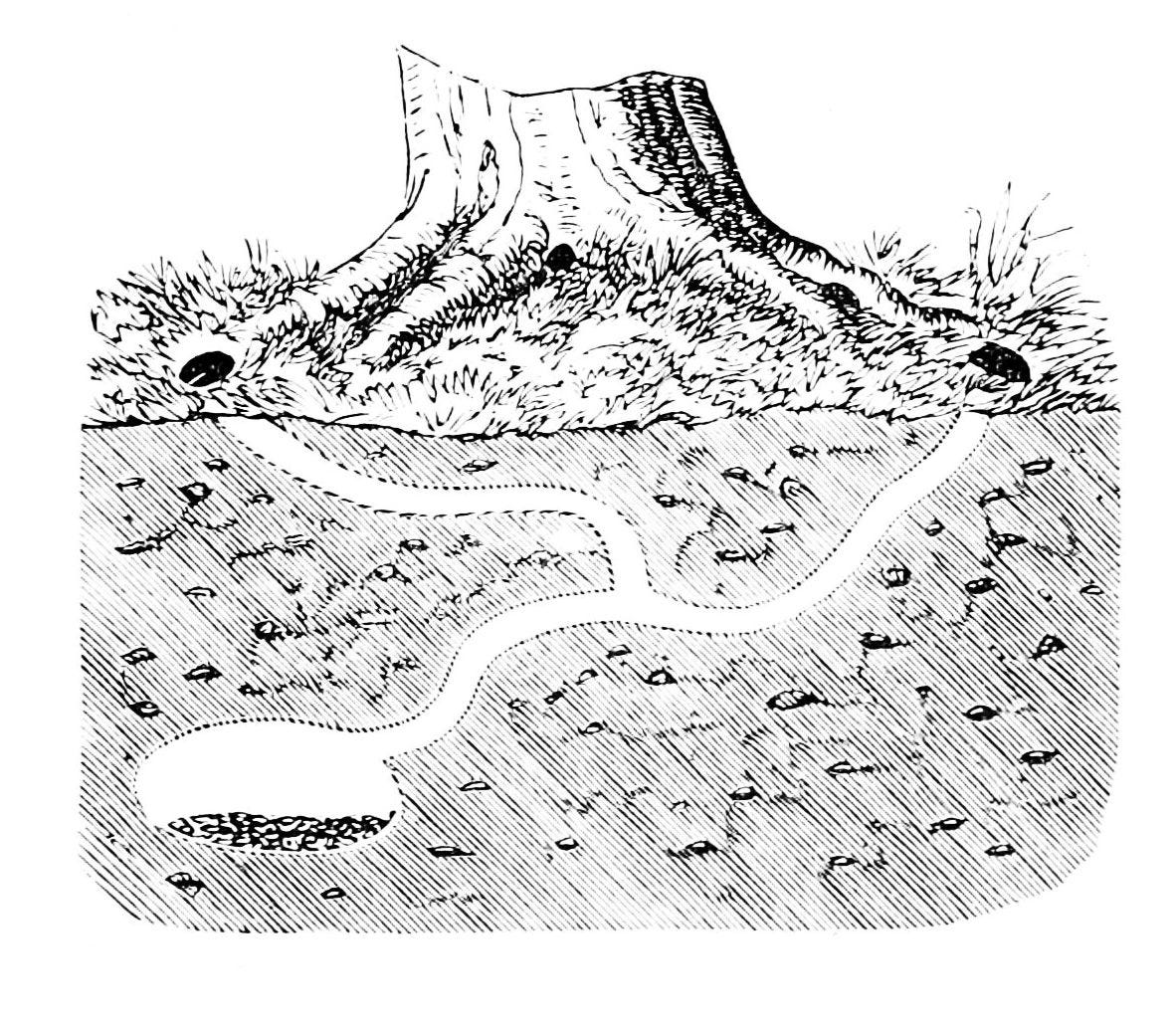

Chipmunks, who live alone after they become independent, hide their stashes in various tunnels in their burrows.

Chipmunks don’t hibernate, but unless they get dug out by a predator, displaced by a more aggressive rodent, or run out of food, they’ll stay snug in that burrow throughout the entire long, frigid winter. It’s hardly “unreasonable” that they spend their summer days gathering and storing food for the harsh months when that will be their only source of sustenance.

Unlike those humans who hoard billions of dollars more than they could possibly use in their and their children’s lifetimes, the unused seeds a jay, squirrel, or chipmunk hoards often germinate, benefitting a great many others besides themselves. Thanks to Blue Jays caching more acorns than they need, oak forests are constantly renewed. Indeed, as glaciers retreated, the extra acorns Blue Jays planted sprouted into oak forests before other trees could get established.

So my little Dizzy’s puffy, peanut-packed cheeks are a sign of hard work and planning for the future, not gluttony or piggishness. And she’s objectively adorable. Interacting with her and my backyard jays makes me feel rich in a way no billions of dollars ever could.

Some raptors hoard their kills sometimes. I thought I saw a redtail do this once. American Kestrels are notorious for this. Dan Klem and his colleague Tim Kimmel first published it in the journal Animal Behavior as graduate students at the University of Illinois at Champaign. Since, there's been I believe a paper and a Master's thesis regarding it. Of course, they refer to it as a cache, but hoard by your good definition is perhaps more descriptively accurate. I like food "larder" as well.

Regarding jays, I believe the first study of them hoarding and planting inadvertently oaks was of the European Jay on the mainland. There's a YouTube video of Bernd Heinrich telling about the jays on his Vermont property planting oaks on it by dropping acorns while enroute to larders. I'll look for it and if I find it, post the title in a reply. Anything by him is most fascinating and rewarding to read and watch and learn from.

Oh Laura! Your pet blue jay/squirrel/chipmunk give us a treat as if we were there...thank you so much!! Polly