Lesser Prairie-Chickens

A slap in the face on the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act

(Listen to the radio/podcast version—significantly shorter—here.)

Being 71 years old has an unexpected dark side. It’s not my awareness of impending doom—I’ve known since I was a small child that every day I live is one day closer to the end of my story, and I’ve lost too many relatives and friends who were decades younger than I am for me to imagine that my own story is supposed to be a long one. And it’s not associated with aches and pains—I’ve been very lucky in that regard. No, the dark side of being 71 is how bitter and angry I’ve become about things I used to be so hopeful about, and how painful it is having a 2 ½ year-old grandson growing up in a world so much poorer in so many ways than the world I’ve been so blessed with.

I was a college freshman active with the first Earth Day in 1970, when we brought so much information about the plight of disappearing species to so many Americans. Within 3 years, public awareness and concern, along with the hard work of biologists, ecologists, birders, naturalists, educators, politically savvy conservationists, and others, led to passage of the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts and the Endangered Species Act, which enjoyed so much popular support that the House passed it with a 392-12 vote (newly-elected Congressman Joe Biden of course voted for it) and the Senate vote was unanimous. When Richard Nixon signed it into law, he stated:

It has only been in recent years that efforts have been undertaken to list and protect those species of animals whose continued existence is in jeopardy. Starting with our national symbol, the bald eagle, we have expanded our concern over the extinction of these animals to include the present list of over 100. We have already found, however, that even the most recent act to protect endangered species, which dates only from 1969, simply does not provide the kind of management tools needed to act early enough to save a vanishing species.

I can’t possibly exaggerate how elated I was. Passage of so much important environmental legislation in such a short time confirmed my belief that with love, understanding, commitment, education, and hard work, it would be possible to restore every declining species and protect a great deal of natural habitat so my generation could bequeath to our children and grandchildren a better world than we were given. Some people try to build up their financial holdings to leave as much as possible to their descendants, but how much more vital to leave clean air and water, and a richer natural world teeming with beautiful birds and other wildlife, for our loved ones and everyone else to share!

Even as many people in my generation were breathing a sigh of relief and moving on to other things, powerful interests were doing everything they could to dismantle all the progress we’d worked so hard to achieve. The birds and other animals originally listed as threatened or endangered got the full benefit of that powerful law. Some, such as Whooping Cranes, Bald Eagles, California Condors, Peregrine Falcons, and Kirtland’s Warblers, enjoy much larger numbers today than they did in 1973. But some already threatened and even endangered birds that weren’t listed from the start have declined even more dramatically in the past 50 years.

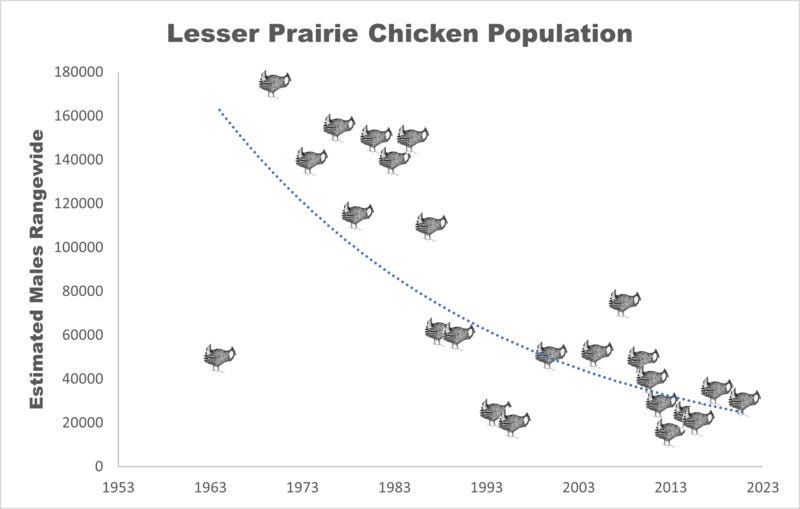

The Lesser Prairie-Chicken is a case in point. This species of the dry short-grass prairies from northwestern Texas and eastern New Mexico, southeastern Colorado, and western Kansas and Oklahoma, has lost 85 percent of its historical range and as much as 99 percent of its population, with the extreme droughts and fires of recent decades even more gravely reducing the species’ chances of survival. If that wasn’t bad enough, the extreme political nature of land use issues in those particular 5 states makes efforts to help it just about impossible.

I saw my first Lesser Prairie-Chicken in Campo, Colorado, in April 1996, when my sister-in-law Jean and I drove there on our own, using directions from a 1995 American Birding Association book called Birdfinder: A Birder's Guide to Planning North American Trips. During my 2013 Big Year, I went on a Colorado birding trip with Kim Eckert to see Lesser Prairie-Chickens, but they’d disappeared from Campo. We saw them at a blind in Holly, where I made a recording of their exuberant chatterings from the blind.

In 2014, I was invited to speak at the “Lek Treks & More” Lesser Prairie-Chicken festival in western Oklahoma, and got to spend one of the most memorable mornings of my life in a photo blind in a lek. Sadly, that blind wasn’t in Oklahoma. We could still see a few birds at a distance in Oklahoma, but the birds were dwindling throughout the area and had vanished from the local lek affording the best photo ops, so in 2013, the festival’s photo blind was at a site in northern Texas. (All the Lesser Prairie-Chicken photos in this post are from that amazing morning.)

In 2021, the Oklahoma festival was discontinued altogether because easily viewed prairie chickens throughout their areas had disappeared. The birds can still be observed in Kansas, where a new festival was started to replace the Oklahoma one. The Kansas festival offers opportunities to see both the Lesser and its long-grass prairie relative, the Greater Prairie-Chicken, at least for now.

Despite how rapidly it has been disappearing before our eyes, the Lesser Prairie-Chicken wasn’t listed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service as “threatened” until 2014, long after it should have been listed as endangered. But a district court judge quickly vacated the new, weaker designation when the Permian Basin Petroleum Association and several New Mexico counties filed a lawsuit challenging the bird being listed at all. The kind of management tools Richard Nixon envisioned so we could “act early enough” to save a vanishing species failed in 1973 when the Lesser Prairie-Chicken wasn’t listed in the first place, failed in the subsequent 42 years when it still wasn’t listed, and failed in 2015 thanks to that politically appointed judge ignoring the science and the Endangered Species Act’s mandate.

On June 1, 2021, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed splitting the species into two segments. The northern one, covering Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, and a portion of Texas, would be listed as merely threatened, and the southern one, covering New Mexico and a portion of Texas where the birds had virtually vanished, as endangered. And six months ago, on November 17, 2022, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service finally upgraded the Lesser Prairie-Chicken’s status to endangered. I was thrilled.

But in late April, exactly 50 years after the Endangered Species Act was passed, the U.S. House Natural Resources Committee (including my own Congressman, Republican Pete Stauber) used the Congressional Review Act to recommend reversing that decision. And on May 3, the Senate voted 50-48 to rescind the Lesser Prairie-Chicken’s endangered designation, the majority including every republican and Joe Manchin (D-West Virginia). If the House also passes the bill, President Biden promised to veto it, but either way, this hyper-partisan vote was a slap in the face to all the scientists and managers charged with safeguarding our natural resources, and to all us Americans who love this splendid all-American bird, found nowhere on the planet except in the United States, a bird vanishing even as I write this.

My dear friend J. Drew Lanham, in addition to writing magnificent poetry and prose, being a wildlife ecologist, and winning a MacArthur Foundation genius award, teaches at Clemson University. He recently took students on a field trip to an extraordinary on-campus space where 220 plus species of birds have been recorded, and found himself complaining to them about how that splendid place had “backslid into disarray and negligent mismanagement.” To protest how decisions were being made, he had resigned from the university committee tasked with managing the land.

In essence I explained how I picked up my toys and went home, butt-sore. In that instant, I caught myself. Here I was talking about management priorities and being an advocate for bird conservation, and I'd straight up quit. On the way to my office afterwards, I called the chair of the committee and told her I wanted back on. That rather than complain, I wanted to help complete what we've been working at so hard for so long. She happily welcomed me back.

Drew wrote that he has a new mantra now: “We can commit to changing a thing, or complaining about a thing. One has the potential to make things better. The other to make you bitter. Choose your way.”

Drew’s words reminded me of Sean Connery’s line in the movie The Untouchables: “What are you prepared to DO?” I may be 71 years old now, much more tired than I used to be, and busy with babysitting my grandson, writing, and birding, but there is too much at stake for me to spend even a moment whining rather than doing what I’ve always done best starting with that first Earth Day—teaching people about the birds I love and trying to get them to care and to make sure their political representatives know that they understand and care. Lesser Prairie-Chickens are in terrible trouble yet powerful, wealthy, politically-connected landowners insist on continuing the drilling, over-grazing, and other activities that are wiping the birds out. Attention must be paid.

Nothing I do may help Lesser Prairie-Chickens, but I’m not too old to at least try. As John Adams once said, “We cannot ensure success, but we can deserve it.”

We can commit to changing a thing, or complaining about a thing. One has the potential to make things better. The other to make you bitter. Choose your way.

—J. Drew Lanham

Love the J Drew Lanham quote at the end with the picture of the prairie chicken