Merlin

A different kind of magician

(Listen to the radio version here.)

In 1988, I put together an April Fools program about the John Chickenfat Sled Bird Race in which I introduced a fictitious underwriter, Earth Angel Bird Emporium, “helping you to attract upscale, trendy birds to your home.” By the ‘90s, Earth Angel was using her fictitious engineering background to develop products like “Earth Angel Bird Song Identification Earrings”—parabola-shaped earrings with tiny microphones that interface with a microchip sewn into the birder’s wide-brimmed hat to whisper correct identifications into the wearer’s ears.

My fictitious character also invented “Earth Angel Bird Identification Binoculars, with a teeny tiny microchip embedded in the binocular housing to identify the birds you see in 12 seconds flat or your money back.” Testimonials for these came from such people as Juliet Montague, using her married name for the first time when she wrote to Earth Angel to say how those binoculars saved Romeo’s life on their wedding night when they weren’t certain if a bird was a nightingale or a lark—knowing for sure it was a lark, which doesn’t start singing until morning, Romeo high-tailed it out of there just in time to escape Juliet’s murderous family. And after Santa Claus got lost and thought he was in Australia, Rudolph used his new Earth Angel Bird Identification Binoculars, World Edition, to identify a Ceylon Frogmouth, proving they were actually in Sri Lanka and saving Christmas.

Earth Angel products were fun to imagine, but now the Cornell Lab of Ornithology has brought my fantasy to life with a simple, free app called, appropriately for a tool melding birds and magic, Merlin.

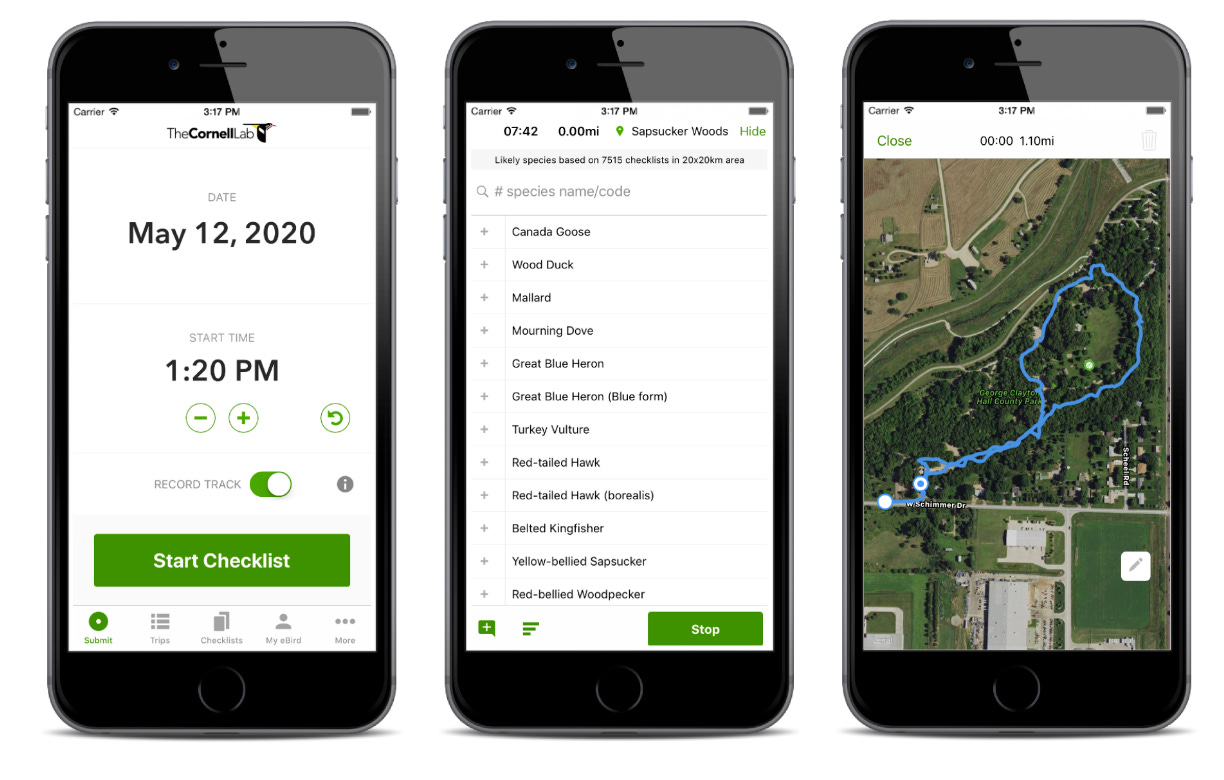

I was working at the Lab in 2008 when Jessie Barry and Chris Wood put together bird identification tutorials for beginners. The first iteration of Merlin sprung out of those, helping people figure out unfamiliar birds by answering a few simple questions—the date and place; the bird’s size compared to a sparrow, robin, crow, and goose; up to three of the bird’s main colors; and what the bird was doing. Merlin instantly listed the possibilities, the most likely at the top, using data from another free Cornell app, eBird, to limit and rank the likely suspects.

eBird, launched in 2002, was originally a free computer program allowing birders to upload our checklists from every outing. The benefit for birders was that eBird kept track of all our birds, keeping not just our life lists but our year and location lists up to date. As more birders used eBird, it also helped us find rare birds others had discovered.

Developing eBird was hugely expensive, involving a lot of Lab resources, but its scientific value has been worth every penny as the body of bird data so essential for ornithological and conservation research grows exponentially.

When smartphones came out, eBird evolved into an app. I open it on my iPhone right when I start birding. The phone gives eBird the date, time, and location so it can generate a checklist of the most likely birds. All I have to do is mark in how many of each species I’ve been seeing whenever it’s convenient along the walk, and tell eBird when I’m done birding—it knows exactly how long I was out and how far I’ve walked. Cornell keeps improving it, making it so useful and easy that the number of users keeps growing. Now close to a million observers submit tens of millions of bird observations every month. As of eBird’s twentieth anniversary in 2022, there were 1.2 billion bird observations in the eBird database.

That database must be both huge and as close to 100 percent accurate as possible for it to be useful for research. So during the two decades since its launch, Cornell has maintained their absolute commitment to making constant improvements so eBird is as easy and useful for birders as possible while working with a cadre of volunteer reviewers to verify unusual species and numbers. eBirders also contribute photos and recordings to document their sightings, building up a huge database of media as well as species. All this has led to an amazing synergy, with most state records committees, breeding bird atlases, and Christmas bird counts now working with eBird, simplifying the workload for compilers even as it’s adding value for the researchers depending on a comprehensive database.

eBird’s huge database is also what makes Cornell’s magical Merlin app possible, and like eBird, Cornell continues to make constant improvements on Merlin while keeping it free for users. Birders can still use it the old-fashioned way, answering those simple questions to identify an unfamiliar bird.

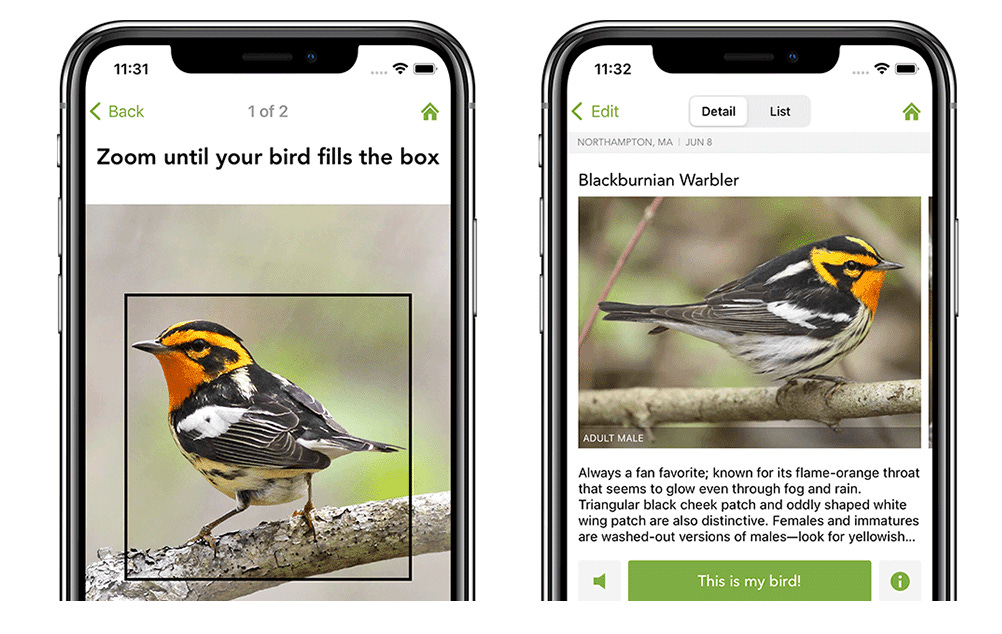

Now Merlin can also identify bird photos with surprising, and ever improving, accuracy.

The Holy Grail of bird identification apps has been developing an app that can identify birds by sound. It was hard enough to develop apps to identify human music—the original Shazam could recognize only specific recordings of songs. If artists covered their own work for an updated recording or live performance, using their own voices and the exact same instruments, the original Shazam could not recognize the new version until it was added to the database.

Bird vocalizations are much trickier. Except with a nearby Whip-poor-will or other nocturnal species breaking into the stillness of the night, we virtually never hear a single bird calling without others piping in in the background, and even Whip-poor-wills usually compete with frogs and insects. Most birds have a variety of different songs and call notes, and some birds mimic other species. Then add in confounding background sounds. How could any algorithm deal with all these difficulties?

Six years ago, before Merlin launched their own sound identification element, I went out with the developer of a commercial app that was supposed to identify birds by sound. We went to one of my favorite local birding spots for me to test it, where I knew we could get close to a variety of common northland birds. The app could not figure out one song if another bird was also singing, so we couldn’t use it most of the time. I had to press the record button the moment I heard an isolated bird song, though it did provide a generous reaction time, starting the recording a few seconds before I pressed the button.

The commercial app’s database, which had to be revised bird by bird by the developers, didn’t include such common species as Sora, Virginia Rail, Marsh Wren, Brown Thrasher, or Swamp Sparrow, the exact hard-to-see birds an app would be most useful in identifying. When I checked afterwards, the database didn’t include 75 of the 175 species that I’d already seen that year in St. Louis and Lake Counties.

The database did include Song Sparrow, but on my test, it misidentified just about every song produced by a nearby Song Sparrow. And the possibilities it provided for a song were listed alphabetically, not in the order of likelihood of each. I could appreciate how difficult and expensive developing such a complex undertaking was, but it was certainly not worth the $9.99 sticker price without serious improvements.

The Cornell Lab’s non-commercial Merlin from the start was powered by eBird. No people had to step in and add species to the database or make judgments about which species are likely in which areas. Every time any of us submit an eBird checklist, we’re contributing to how Merlin assesses the possibilities and the likelihood of each local bird.

Merlin is magical in other ways, too. We don’t have to start and stop it to figure out songs one by one. We open just open the app, press the Sound ID button, and it magically starts listing every bird it hears. As it detects a listed bird’s song again, it highlights it, so we can tease out which sound goes with which species, making it fun and easy for beginners to learn their backyard birds or for more advanced birders to figure out unfamiliar songs in a new place.

I use Merlin a lot. As I’ve lost my high-frequency hearing, it helps me detect Blackburnian and Golden-winged Warblers, LeConte’s Sparrows, and other songs too high-pitched for me to hear. I don’t list them on my eBird checklist until I’ve actually seen them, but Merlin is how I know to look for them. When I make my own bird recordings and open them on my computer, I can’t hear those same high-pitched songs, but I can see them on the spectrographs, and Merlin can usually tell me what they are. If that isn’t magic, what is?

Merlin isn’t 100 percent accurate, so we should never use its results for our eBird checklists without verifying, especially when it lists something rare or in the wrong habitat. Just a few weeks ago I got excited when it listed a singing Philadelphia Vireo, but when I tracked the singer down, he turned out to be a much more ubiquitous Red-eyed Vireo.

But don’t let perfection become the enemy of the good—by any grading scale, Merlin deserves an A+. When I’ve used it in the field, it’s been at least 97 percent accurate at picking out both those high-frequency songs and also songs well within my hearing range that I was overlooking as I focused on other sounds.

Merlin. It’s useful, it’s fun, and it’s absolutely free. I call it genuine magic.