(Listen to the radio version here. The email version went out with an error—the moon landing did NOT happen in 1970 and I KNEW that!)

Every morning for the past week, I’ve been listening to four different robins and three different House Wrens singing about their territories. The robins start up well before first light; the wrens hold off until dawn. Russ put a chain-link fence around our backyard over 40 years ago to keep our toddlers and dog in the yard, but I suppose it also serves as something of a territorial declaration so we don’t have to get out there in the wee hours to sing our own version of “This Land Is MY Land” to the world.

Today is flag day, when many Americans display a piece of cloth that represents a different kind of territoriality, not for individuals or families but for a whole nation. Of course, that flag never did represent all of us, but a kind of national pride stirred within a lot of us in 1969 when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stuck one on the moon.

This week, I heard from one of my childhood friends who had somehow dug up the transcript of a radio program I did on Veterans Day 2003. I can’t find the sound file but decided to reconfigure it for today.

I come from a family of veterans. My grandpa fought in World War I, my father-in-law in WWII, three of my uncles in the Korean War, and my big brother in Vietnam.

When I told my grandpa how proud I was of him being a brave soldier, he told me he hadn’t been brave at all—he only went because he had no say in the matter. He said the way you judge the people who do have a say in these matters—the ones making the decisions that force the military and the people to make big sacrifices—is by how carefully they consider every alternative before sending people off to die.

My grandpa said it’s easy to die for your country—all you have to do is be in the wrong place at the wrong time. The hard thing is to live for your country, trying your best to place the common good above personal selfishness. My grandpa said that birds were way braver than we humans—they never sent anyone off to kill or die for them. When a bird has a territorial dispute, it fights its own battle and stops the moment it makes its point, without that peculiarly human impulse to destroy and humiliate.

I thought about my Grandpa one summer afternoon in 2003 when I found myself in Washington, DC, walking along the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. House Sparrows hopped at my feet, cardinals and robins sang from the trees, and an occasional Great Blue Heron or Black-crowned Night Heron flew overhead on its way to or from the Reflecting Pool.

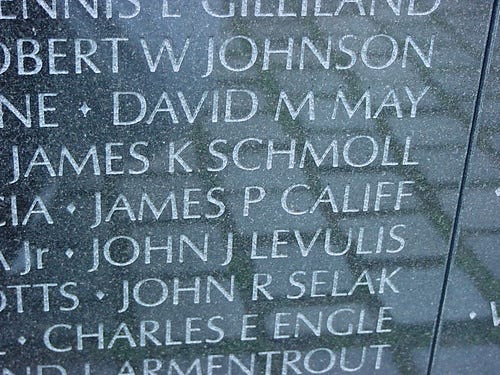

Some of the birds I saw directly, others reflected in the black marble as I searched for one particular name—the name of a boy I sat next to in several classes in 7th grade—Jim Califf. He was a nice boy, and I wanted to touch his name in the marble and somehow make a connection. But there are 57,685 names on that wall—searching for Jim was like searching for one particular daffodil in a huge field of daffodils.

When you enter the Memorial, you see only a few names on the wall, but as you descend, the walls grow deeper and deeper, covered with name after name after name of boys and men and girls and women who never got to grow old, who were all in it together over there and are still in it together here and now, bound as one forever in stone.

Every now and then as I searched for Jim's name I found myself looking into my own eyes mirrored in the wall, a name caught in the reflection, the name of a boy or man who isn't a real person to me but sure was to himself and the ones he loved. Names are so particular, so personal, and yet so anonymous. I was overwhelmed with sadness. So very many names.

Finally I discovered a directory—a book thicker than the Chicago phone book with the names arranged alphabetically, and there was James Patrick Califf, from Northlake, Illinois, born September 15, 1950, died February 21, 1971, before he was old enough to drink a beer. He wasn't the kind of boy who planned on going to college, and he sure didn't have any connections, which is how he, like my brother Jim, ended up in Vietnam in the first place. But his eyes wrinkled when he smiled, he laughed at my jokes and I laughed at his, and he was one of the nicest kids I knew.

Even after the directory pointed me to the right section of the wall, there were so many names to search through. The wall appeared blacker and yet strangely more mirror-like when the sun came out from behind the few clouds, and the reflections of the flying birds and robins running on the lawn were muted in color, as if they, too, felt somber knowing that there are too many names carved into that stone wall, the marble as cold and black as the hearts and lies of the people who sent them there.

But the wall is also as cold and black as the night sky, a place you can look to when you're feeling loss. If you don't find peace and quiet, you at least feel closer somehow to God and nature and other things bigger than yourself. And standing at that wall, you get the feeling that even with the birds singing overhead, or maybe because of them, if you whisper very softly, the person you lost will hear you and know that someone still notices that he’s gone.

The hard thing is to live for your country, trying your best to place the common good above personal selfishness.

A beautiful piece Laura! Everyone should read it. It was my parent’s wedding anniversary and always meant a great deal to our family.