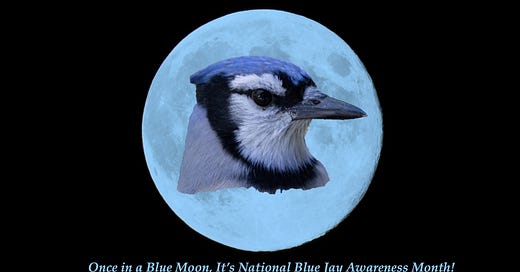

National Blue Jay Awareness Month!

August is one of my favorite months anyway, but this month there's also a blue moon.

(Listen to the radio version here.)

As a birder, I associate every month of the year with wonderful things, and August is one of my favorites. The thrills of spring migration peak in May, songs of local nesting birds peak in June, and then in July, everything quiets down as birds raising young try to stay as inconspicuous as possible. Now in August, most fledglings are full-grown, their parents having supplied all the nutrients to grow all that new baby bird tissue. These fledglings have grown increasingly irrepressible, wandering about figuring out how and where to find their own food even as they continue to beg for handouts from their harried parents whose own bodies have grown increasingly depleted.

Very few young songbirds can survive on their own when they leave the nest. Like human teenagers who buy fast food and snacks but still get fed by their parents at home, these fledgling birds figure out how to get more and more food on their own even as they continue to be subsidized by their parents. Blue Jays often fledge from the nest before they can fly. The first few days, with one or more babies in the nest and one or more babies out of it going every which way like toddlers let loose in a toy store, the parents try to be everywhere at once, and things get crazier before they settle down. Now the fledglings are more capable but still need occasional feedings and protection.

Baby chickadees tend to leave their nest cavity all within a few hours rather than days, and the five, six, or more chicks are already capable of flying when they first light out; nevertheless, keeping them together is just as tricky for their parents as it is for Blue Jays. Either way, it’s not easy being a parent bird.

Feathers are both sturdy and fragile. Flight, weathering, and general wear and tear take a toll, and so most songbirds replace all their feathers once a year in a process called molting. Each old outer feather drops out as a replacement starts growing in, but it can take days or even weeks for that new feather to reach full size, so molting normally happens when the risk of hypothermia is low. Year-round resident birds here in the north often molt in late summer before nights get cold; they’ll have their thickest, newest feathers fully grown in before winter, the outer feathers supplemented with a great many hidden down feathers. Growing new plumage requires a lot of nutrients, but up here in late summer food is still abundant and birds are mostly finished sharing what they find with their young.

During most of the year, Blue Jays and chickadees are wonderfully handsome, but not in August, when molting adults can look almost comically ridiculous, some Blue Jays even losing all their head feathers at once.

It’s strange to see the poor, disheveled parents feeding babies that are in fine fettle, but as the month and molting progress, the adults will start looking like their old selves again.

Unfortunately, by then a lot of us birders won’t be paying attention, distracted because August is also the month that migration kicks in, activity at our birdbaths becomes especially fun, and Cedar Waxwings start gathering in flocks to feast on fruits and sally forth to catch insects on the wing. Nighthawk and hummingbird migration will peak in the next two or three weeks, and a host of warblers and the first raptors will also be passing through in increasing numbers.

This August I’m paying special attention to my Blue Jays. Ever since December 1990, a month with two full moons, I’ve been calling every month with a Blue Moon “National Blue Jay Awareness Month.” In the next two weeks I’ll be putting together at least a few blog posts and radio segments about the species we call the Blue Jay, and also about other blue jay species. We won’t have another month with two full moons until May 2026, so enjoy National Blue Jay Awareness Month while you can.