(Listen to the radio version here.)

This year and last, I spent part of April on a birding tour in south Florida. One of the well-known elements of the company I went with, Victor Emanuel Nature Tours, is the fine dining opportunities, but ironically, one of the well-known elements of my personal birding style is to skip the indoor dining and grab my food on the run. On my Big Year in 2013, there were at least a couple of days when I lived entirely on Fig Newtons, Snapple Peach Tea, and water, and even when I was better prepared, I often just ate peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. When there are birds to be seen, why waste time indoors?

So when I’m with a group of normal human beings who enjoy eating at a restaurant, I often sneak away to look at birds in the area, even if I’m stuck in a restaurant parking lot.

On my tours to south Florida, during the days we stayed in Homestead, our group stopped for breakfast while it was still dark at a lovely little restaurant that opened early. I of course got restless between ordering my food and it being served, and then between my finishing eating and the rest of the group being ready to leave, so during both those intervals, I went outside to stand on the sidewalk near enough to a window that I could sort of keep track of what the group was up to while I mostly focused on nighthawks. I occasionally picked one out in the twilit sky, but I mostly used my ears as they called out their peent calls and occasionally boomed. (I don’t have any photos but do have some sound recordings of nighthawks booming linked on my Common Nighthawk Species Page.)

“Booming” is not the word I would have used for the nighthawk courtship and territorial display. To impress or attract a female or to intimidate a territorial intruder, males fly to a height slightly above the treetops or downtown buildings and abruptly dive down at breakneck speed. As they peel out of the dive—often surprisingly close to the ground—they flex their wings downward, the rush of air across the wingtips making a deep booming or whooshing sound.

I first observed this from the parking lot at the Natural Resources Building on the Michigan State University campus, and each time I saw the dive, I was sure the bird was going to crash. In my imagination, the bird suddenly thought so, too, yelling out a deep AUGH! as he pulled out at the very last moment.

I used to be able to see and hear nighthawks courting in downtown Duluth and at both the UMD and College of St. Scholastica campuses, but nesting here in town declined gravely for two reasons: The local populations of both crows and Ring-billed Gulls mushroomed starting in the 1980s, and those opportunists quickly learned to recognize tasty nighthawk eggs on flat roofs; and building design moved away from the rock-ballasted flat roofs that mimic the bare patches of gravel where nighthawks naturally nest. Newer, “clad” roof designs get much hotter, don’t provide any camouflage for the mottled eggs, and the eggs don’t stay in place due to the incline for drainage.

I specialized on nighthawks when I was a bird rehabber in the 1980s and 90s. Those individual birds and all kinds of wonderful encounters with breeding and migrating nighthawks place them in my “Top Ten” favorite birds of all time.

Fun as it is watching and, especially, listening to them courting at twilight in late spring and early summer, my most thrilling encounters with nighthawks happen during August and early September as they course through during fall migration. Here in Duluth, the birds we see mostly bred in the Great Plains and boreal forest regions of Canada, and they’re all on their way to South America. Some individuals will cover more than 7,000 miles to get to their wintering area. That is, 7,000 miles as the crow flies. As the nighthawk flies, the distance covered is much, much more because nighthawks dart this way and that hunting for the only thing their bodies are capable of ingesting—insects on the wing.

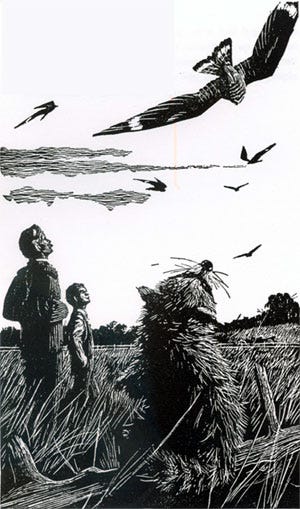

We may see the first migrating groups fluttering about in the afternoon sky at the end of July, the numbers mushrooming as we reach mid- and late-August. Lots of nighthawks may concentrate over a good, buggy field for hours in the afternoon, but if we pay attention, we can usually discern a general southward trend or, here along the north shore of Lake Superior, a southwestern trend (the birds must clear the lake to avoid dangerous downdrafts over the water) as they mosey along toward their destination. As afternoon leads to evening and more and more individual birds are loaded up on calories, they work their way higher and higher in the sky, their flight growing less zigzagged as they change their primary focus from eating to covering miles.

Nighthawks are seldom banded, and even less often are banded nighthawks ever retrapped, yet one banded nighthawk was recaptured and released again when she was at least nine years old. How is it possible for a 3-ounce bird to fly so many thousands of miles every year for so many years? Long ago, an ornithologist calculated that nesting Barn Swallows each cover about 600 miles every day right in their nesting area, darting and swooping every which way to catch flying insects for themselves and their young. Nighthawks probably do about the same. Back in 1987, when Russ’s and my car’s odometer hit 100,000 miles, I did a radio program about birds, including nighthawks, flying much further than that over their lifetimes.

We used to get lots of significant flights and a few ginormous ones every August, but most went uncounted. On August 26, 1990, a huge flight inspired Kim Eckert, Dudley Edmondson, and Mike Hendrickson to go up to the Lakewood Pumping station where they counted an amazing 43,690 in just 2 ½ hours—a vast undercount of the day’s flight because it was so huge before they decided to quantify it.

This past week, a lot of people were thrilling at the nighthawk flight from Hawk Ridge and several Duluth neighborhoods. I saw plenty, but from my yard they were mostly very high or way off along the horizon. On Monday, August 26, the anniversary of that big Lakewood Pumping Station flight, Sean McLaughlin and Marie Chappell counted 11,970 at Hawk Ridge from 6:05 am through 4:05 pm, and then Steve Kolbe counted 23,050 at a spot a mile or so east of there from 5 pm through 8:30, making the nighthawk total more than 35,000 over the course of the day.

It’s impossible to predict weeks or even several days in advance which day will have the biggest flight. If you got to Duluth on Tuesday, the day after Monday’s huge total, the combined total was only 239, and on Wednesday was only 11. Last year on August 26, the combined total was only 3!

So seeing a big nighthawk flight is as serendipitous as it is stupendous. Like Shakespeare’s Prospero or the Maltese Falcon, it’s the stuff dreams are made of.