(I split this into two podcasts: “Why are nighthawks declining?” and “Nighthawks: a reason for hope.”)

Last Saturday’s nighthawk flight was spectacular. After dark, my dear friend Erik Bruhnke posted this on Facebook:

Tonight was simply mesmerizing, with a "lifer" experience of seeing and counting more nighthawks than I've ever seen in one day.

The weather conditions were prime for a big nighthawk flight through the Duluth area this evening. Late August is prime time for seeing these birds migrate through the Duluth area. It was a pretty hot day and very warm afternoon, with barely a breeze in the air. These conditions welcome late-summer insects hatches high in the air, which are attractive to many insectivorous birds like nighthawks. I feel fortunate to have a little backyard along one of the lowest parts of the North Shore (basically near the bottom of the migratory funnel).

This evening I counted 18,695 Common Nighthawks from my yard in just under 3.5 hours. There were times when I found myself getting watery-eyed while clicking them, being just delighted at the spectacle, each one erratically-meandering and feeding among the others. The sunset was pretty wonderful too, with lots of dragonflies on the move and a few Monarchs. What a show of migration!

Erik is almost a part of my family, so I was especially happy that he had this splendid experience. One of the biggest nighthawk flights I ever witnessed was coming home from Port Wing, Wisconsin, after we celebrated Russ’s dad’s birthday one August 14 in the 1980s. Fortunately, Russ was driving because I couldn’t pull my eyes away from the non-stop stream of nighthawks fluttering this way and that along the South Shore, and then streaming along the North Shore. I don’t think there was one second on that 75-minute drive when I couldn’t see dozens. I could hardly make an accurate count from the moving car, but I was riveted by the spectacle.

In the 1980s and 90s, we used to see at least a few nighthawks, and often hundreds or thousands, almost every pleasant late August afternoon and evening, migration peaking on one or two huge days. That was at the point in my life when family obligations made it impossible to sit and count for hours at a time even on the big days, much less every single day. Fortunately, those family activities—Russ’s dad’s birthday, walking my sons to Boy Scout meetings half a mile away, kids’ soccer games—made it easy to at least observe the flights if not to quantify the magnitude. I almost missed Tommy’s first soccer goal, mesmerized by hundreds of nighthawks feeding over the field—fortunately, Russ was next to me to dig his elbow into my side just in time. I did write back then of many occasions when I counted thousands in a single hour from my yard, but I’m afraid for me the huge movements were like August’s wild blueberries—abundant and there to enjoy, not to count.

August nighthawks are also as silent as blueberries, so few people notice them passing over. I wrote about their Duluth migration in 1988, “It’s like an exotic secret right out in the open yet known only to a select few.” Unfortunately, none of us kept close track of the dates nor the time we started or ended those counts except on August 26, 1990 when, during one big flight, Mike Hendrickson, Kim Eckert, and Dudley Edmondson went up to the Lakewood Pumping station and in 2 ½ hours, counted an amazing 43,690. That was an undercount for the night. The only reason they went to the pumphouse in the first place was that they saw so many passing through—the flight began an hour or two before that count even began.

It’s improbable that the one night anyone made a concerted effort to count them just happened to be the night of the biggest nighthawk migration ever over Duluth. It is simply the biggest flight anyone counted. As I recall, that night’s flight did indeed seem huge to all of us paying attention, but not extraordinarily so—many of us talked about how we wished someone had been counting so completely on the many other big nights we remembered.

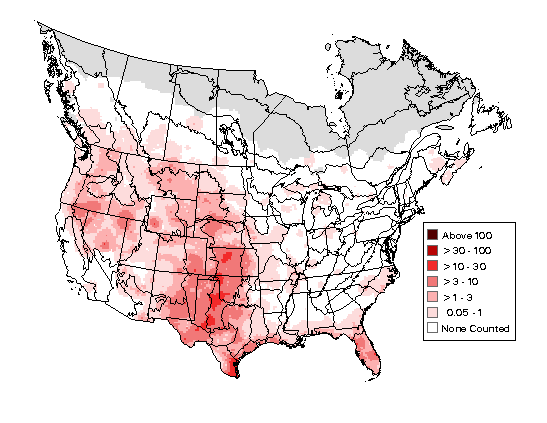

Based on limited GPS tracking efforts, many of the nighthawks flying over Duluth each fall are coming from western and northwestern Canada; I suspect many are also coming from western Minnesota through the Dakotas and the northwestern United States. The species is widespread and nests, or once nested, on flat roofs as well as more natural spots in most towns, small cities, and major metropolitan areas.

Nighthawks feed exclusively on flying insects which go straight down the hatch as they fly into the bugs with their capacious mouth wide open. Their vestigial tongue and beak are useless for picking up food items or anything else, as I learned firsthand during the years I spent as a licensed wildlife rehabber.

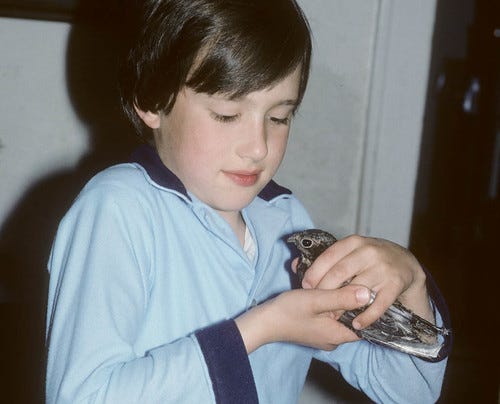

As a stay-at-home mom, I had lots of time to give individual birds special care, and my kids also learned how to feed them, so I ended up specializing on them. With so many nesting in and near Duluth and passing through in such huge numbers in August, people often found dead and injured ones after collisions with wires and cars, and I’d end up caring for several each year.

One male whose wing was too damaged at the bend to ever fly again ended up as my education bird Fred (named for Mr. Rogers for his gentle nature). I lived with him for six years. Few other rehabbers could keep nighthawks alive for long because the birds required special handfeeding for every bite of food they took in. (Two decades after I let my license expire, I still hear from rehabbers who need information and help when trying to keep an injured nighthawk alive.)

Despite how widespread nighthawks are, and how they nest, or once nested, on flat roofs in virtually every town, city, and major metropolitan area of the United States and Canada, this is one of the most understudied of all the common species in America, partly because of the difficulties of maintaining them in captivity but mostly because of their crepuscular habits.

The Breeding Bird Survey protocol is far from ideal for surveying nighthawks. Survey routes all begin precisely 30 minutes before dawn, and so crepuscular birds like nighthawks can be heard only on the first few stops of any route.

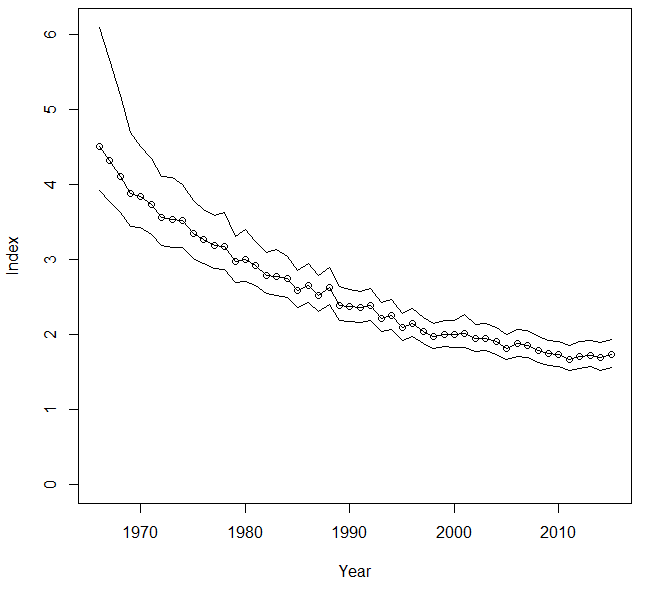

But the BBS is the only source of consistent, continent-wide data going back more than half a century, and it shows a steep decline in nighthawk numbers between the Survey’s start in 1966 (when DDT, targeting the insects that are their only source of food, was being heavily used) and 2015.

Cornell’s Birds of the World species account (access requires a subscription), written in 2011, notes, “Recent (albeit limited) Breeding Bird Survey data suggest a substantial decline in numbers of this species, perhaps owing to increased predation, indiscriminate use of pesticides leading to lowered insect numbers, or habitat loss.” The nighthawk has been listed as Threatened in Canada, where a decline of about 50 percent has been noted there over the past 3 generations. Canadian researcher J. A. Wedgwood conducted a thorough survey of Common Nighthawks in the city of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in the summer of 1971; when he repeated the survey in 1990, he found a 42 percent decrease. In the United States, the species is considered critically imperiled or imperiled in Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Delaware.

Why is the species in so much trouble? Most DDT use in the United States ended in 1972, but the “insect apocalypse” that began with this insidious pesticide continues, and insecticides continue to be the method of choice for dealing with insect problems. Aerial spraying of Bacillus thuringiensis for gypsy moths and spruce budworm in my own area is still happening every year, and the people touting its applications keep assuring us that it doesn’t harm people, pets, mammals, or birds while neglecting to mention that Bt is lethal to all lepidopteran larvae, killing monarch and other butterfly and moth caterpillars; moths are an important element of the nighthawk menu. And decades of this spraying haven’t had much or any real impact on the pests it’s ostensibly “controlling.”

The vast reduction in insect prey is not the only problem facing nighthawks. In many areas, they’ve stopped using flat roofs for nesting for at least two different reasons. Urban gull and crow populations have been soaring since the 1980s here in Duluth and elsewhere. Once these egg predators figure out the roof-nesting habits of nighthawks, who have absolutely no defenses, predation on eggs and chicks becomes too overwhelming for the birds to sustain.

Meanwhile, rooftop design has been changing. Most flat roofs had once been covered with tar paper held in place by rocks, which provided excellent nesting habitat for nighthawks, terns, and a few other ground nesters. But construction methods and materials have changed, and now many rooftops are clad in rubberized asphalt, which these cryptically-colored birds cannot hide against. And asphalt gets so hot that rehabbers and banders have documented nighthawks with blistered feet; obviously, this type of roof can get too hot for eggs or chicks to survive. Maine researcher V. Marzilli found that gravel pads set in the corners of rubberized roofs can provide suitable nesting sites, but tragically, if nighthawk chicks wander off the gravel pad onto a roof that gets excessively hot, they may burn their feet, and meanwhile, crows have learned to recognize the gravel pads as places where they can pick up nighthawk chicks. (I wrote about this issue in my 2006 book, 101 Ways to Help Birds: #56. Make flat roofs nighthawk-friendly. )

Nighthawks are vastly understudied on their wintering grounds in South America, where pesticides and habitat destruction may also have had an impact on nighthawk numbers.

But if the species has declined so dramatically, how can people still be counting so many here in Duluth? Our city does seem to be the epicenter of their migration, so ornithologist Gerald Niemi and others concerned about their decline started systematically counting nighthawk migration in Duluth in 2008 from an apartment building in eastern Duluth with a view of the lake and inland. (My son Tom was among the counters for a year or two.) Steve Kolbe, a graduate student focusing on nighthawk migration who may love the species as much as I do, started participating in 2014 and is still counting them.

In 2019, the NRRI wrote a press release saying:

The common nighthawk has been designated as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Breeding bird surveys out of Canada say birds that rely on flying insects are declining dramatically, about six percent per year. And the Partners in Flight organization identified the nighthawks as a species in steep decline.

“But we’re not seeing that at all,” [Steve Kolbe] said. “We’re actually seeing an increase in our counts in the last 11 years.”

Dan Kraker of Minnesota Public Radio said in 2020, “Kolbe typically counts between 20,000 and 25,000 nighthawks a year. And that number has held steady, which is a little surprising.”

That year, John Myers of the Duluth News-Tribune emphasized the same point:

13 years of nighthawk counting by NRRI personnel has found no noticeable decrease in the migration over Duluth. The annual count here “fluctuates a lot depending on the weather. But over the long term, we’ve seen an insignificant increase, not a decrease. We don’t know why that is,’’ Kolbe said.

It’s critical to remember that 2008 was simply the year this count started, not a baseline of what nighthawk numbers have always been. We’d never say that Ivory-billed Woodpecker numbers have held steady since the Breeding Bird Survey began in 1966—that species’ decline toward extinction began long before systematic study of it was possible, just as the Common Nighthawk’s decline was obvious and measurable for decades before the Duluth count began. That big migration Hendrickson, Eckert, and Edmondson documented in 1990 was far from the only nighthawk migration night of 1990, yet even though it was an undercount, it was more than double an entire year’s average now.

But fortunately, the new count data do suggest that the decline in nighthawk numbers has leveled off. We can still relish some thrillingly joyful August evenings when they fill the sky, but there is no evidence whatsoever that the species is regaining its former numbers, nor that the steep declines in the flying insects it needs are recovering.

As an obligate insectivore that once thrived in a wide variety of habitats throughout most of North America, the Common Nighthawk is an important indicator species as well as a lovable, inoffensive bird deserving protection and study in its own right. I hope Steve Kolbe’s Duluth migration count, and many more systematic studies of it on its breeding and wintering grounds, continue long into the future.

I have yet to see my first nighthawk, but I am looking! Thanks for posting!