(Listen to the radio version here.)

On May 3, 1975, two months after I started birding, I saw my very first woodpecker—the #20 bird on my life list—and it was a stunner: a gorgeous Red-headed Woodpecker. The entire head, including the face, neck, and crown, was solid red; the upper back, wings, and tail gleaming black except for a pure white rump and large wing patch; and the undersides pure white. When it flew, the white on the wings and rump stood out brilliantly, making it easy to track to the next tree, and breathtaking when it sallied out to snatch an insect in flight. I was thrilled!

This was at Baker Woodlot, where I’d also seen my first chickadee, and close to the Natural Resources building where Russ had an office and I was taking a class, so I checked back several times in the following days. Now that I knew where to look and what to listen for, I found one or two just about every time.

It took over a week longer for me to find and identify my first Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers and Northern Flicker. Perhaps that’s why for years, the Red-headed Woodpecker defined the woodpecker family for me. That summer, I took an ornithology class at the Kellogg Biological Station, and our class saw Red-headed Woodpeckers on most of our outings. The next spring, I took a field trip to Point Pelee in Ontario and visited the Morton Arboretum outside Chicago; I saw Red-headed Woodpeckers in both places. That summer and fall, after we moved to Madison, Wisconsin, I saw Red-headed Woodpeckers—adults and young both—just about every time I went to my favorite Madison spot, Picnic Point. They seemed both common and ubiquitous.

When we moved to Duluth in 1981, I didn’t see them nearly as often as I used to—Red-headed Woodpeckers tend to stick to areas with lots of oak trees, and my neighborhood’s clay soil doesn’t support many of them. But during the 80s, I still saw them in my neighborhood every year during fall migration. Once (long before I was photographing birds) I even saw what appeared to be a whole family—three young and two adults—on the telephone pole right across the street from my house!

With their simple, straightforward red, white, and black plumage, Red-headed Woodpeckers are easy to identify, both dead and alive. And as I started paying attention, I saw more of them dead than alive, invariably crushed along highways. I soon learned that Red-headed Woodpeckers are exceptionally vulnerable to collisions with cars because they tend to fly across open areas at just about exactly windshield height. By the time I was fully appreciating that fact, I was also starting to discover that they weren’t as common as they had once been—a trend that is ongoing to this day.

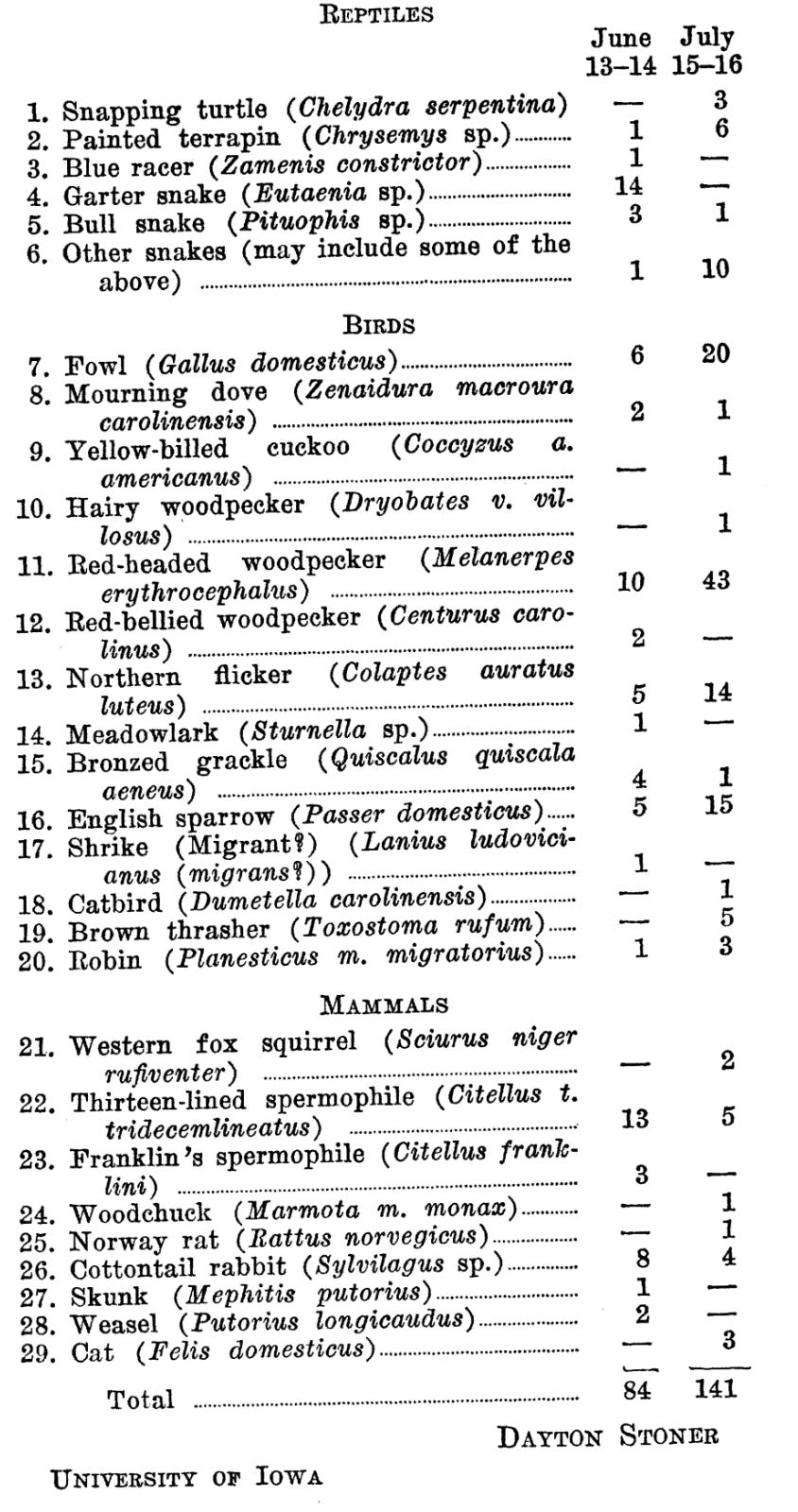

We’ve long known that Red-headed Woodpeckers are more vulnerable than most birds to being killed on roads. One hundred years ago, in June 1924, Dayton and Lillian Stoner took a road trip by car from Iowa City to the Iowa Lakeside Laboratory 316 miles away, making the return trip a few weeks later. They seldom exceeded 25 miles per hour. In both directions, the couple documented every dead vertebrate animal they found along the way and published their findings in the January 16, 1925 issue of Science. They described the terrain as:

typical Iowa farming communities, for the most part moderately thickly populated and supplied with the usual farm buildings. Prairie, marsh and woodland were also represented as were various types of soil and vegetation supported by them… About 200 miles of the road were graveled; the remainder was just "plain dirt," most of which had been brought to grade.

You wouldn’t think they’d have found too many dead animals considering how slow cars traveled a hundred years ago, especially on gravel and dirt roads, but they listed a total of 225 identifiable creatures—84 in June and 141 on the return trip in July when more inexperienced young were about. The species composition and numbers of each varied between the two trips, presumably because of differences in activity patterns during the various species’ breeding seasons.

On both trips, Red-headed Woodpeckers vastly outnumbered every other bird. Garter snakes and thirteen-lined ground-squirrels slightly outnumbered the woodpeckers in June; no animals came close in July. In total, Red-headed Woodpeckers accounted for 53 of the 225 dead animals, or 24 percent of the total mortality. They traveled mostly through farm country so a lot of chickens were among the dead, but even counting baby chicks who can’t fly at all, the total number of fowl killed was half that of Red-headed Woodpeckers.

The Stoners suggested that the ground-feeding habits of Red-headed Woodpeckers contributed to their road mortality. That’s almost certainly true, yet flickers, probably just as common then and living in the same areas, spend much more time on the ground than do Red-headeds, yet flickers died at half the rate. All woodpeckers have a swoopy flight, but when crossing open areas, flickers seem to fly much higher—at or above the treeline. The roads on which I was observing so much Red-headed Woodpecker mortality weren’t backcountry roads where many might be feeding on the ground, but on major highways.

Highway mortality is one major reason why the Red-headed Woodpecker has been designated a Watch List species by Partners in Flight; a Minnesota Species of Greatest Conservation Need by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, and a Target Conservation Species by Audubon Minnesota. The other major factor is competition from European Starlings, who take over their nest cavities.

Starlings, who cannot excavate their own cavities, are almost exactly the same size as Red-headed Woodpeckers, averaging just a tiny bit longer and heavier, making Red-headed Woodpecker cavities ideal, and starlings are much more aggressive than the woodpeckers, sometimes even killing them when taking over their cavity. When evicted, the woodpeckers do excavate a new cavity, but this delays their nesting period. Red-headed Woodpeckers can nest twice in a single season, but when nesting is delayed thanks to starlings, they lose that option, and starlings sometimes take over their second nest cavity as well.

The Red-headed Woodpecker is in decline throughout its range, but it’s doing worse in Minnesota than elsewhere. Since 1967, when the Breeding Bird Survey began, it has experienced a significant average annual decline of more than 6 percent in the state, representing a cumulative loss of 95 percent since the survey began.

Its status has improved only marginally since 2005—it’s not increasing or even close to stabilizing, but now the average annual decline is slightly less than 5 percent per year. No other state, province, or ecological region has experienced a more significant decline.

Since the 1980s, I haven’t been seeing Red-headed Woodpeckers regularly in Duluth, but in the past few years, there’s been a noticeable uptick in sightings around here, including right here on Peabody Street.

This month there have been a few reports not far from here in Lester Park, and one at Park Point on Tuesday morning, which all the people on Duluth Audubon’s warbler walk got to enjoy.

That afternoon, my neighbor Jeanne saw one a few blocks from here—I got there too late—and then she saw one on Wednesday near her yard. It was still present when I was pulling my car out to babysit Walter, so Jeanne alerted me and I at least heard it. Then, oddly enough, on Friday I saw two in Walter’s backyard while I was babysitting. I felt so lucky!

It’s impossible to know at this point whether these sightings were just a fluke of this year’s spring migration or whether the Red-headed Woodpecker is enjoying a bit of a surge, but either way, it’s wonderful getting to enjoy these charismatic birds again, even briefly.

Emily Dickinson died in 1886, the same year the modern automobile was invented and four years before starlings were introduced to America. Had she any inkling what was to befall these common yet beautiful and homey birds, she might have written, “Hope is the thing with red, white, and black feathers that perches in the soul.”

Thanks, Laura.

This is the first year since we've lived here - 10 years in NW Wisconsin - that we haven't had Red-headed Woodpeckers nesting in the yard or close by. I know they are not too far away because I can sometimes hear them and they still do visit our feeders from time to time, but they are not a fixture as they have been previously. I miss them, but I expect the other birds are pleased because they are very aggressive. I've seen one harass a Pileated Woodpecker into leaving the suet feeder, and they absolutely dominate the Red-bellied Woodpeckers at the feeder. Even the juveniles seem to think they are king of the hill.

They leave us in the fall, except for once when one or more of them stayed all winter. Sometimes one will show up in the middle of winter, most notably the year of the polar vortex, when the temperature reached -40C/F, one arrived at the coldest possible time. It survived, sticking around until March.

Anyway, nice article and thank you for letting me reminisce about our woodpeckers.