Review: Kenn Kaufman's The Birds That Audubon Missed

A clear-eyed and exciting portrait of a time and place that have long ago disappeared, and an important and timely book as well

(Listen to the radio version of Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

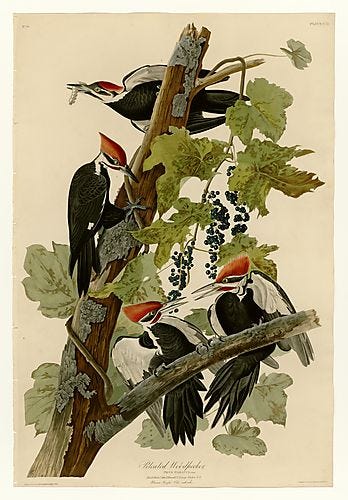

When I first learned that Kenn Kaufman was writing a book about Audubon’s artwork and his indefatigable quest to paint every bird in America, I was thrilled. Most of Audubon’s artwork didn’t appeal to me, but I was truly in love with a few of his paintings. The very first year I started birding, Russ and I bought two large prints—Audubon’s Wood Duck and Pileated Woodpecker—at the Art Institute of Chicago and had them framed. They’ve hung in a place of honor in our living room ever since. (We didn’t realize at the time that we should have used glass that was 100 percent UV filtering, and they’ve unfortunately faded over time, but I can’t bear to part with them.)

That Wood Duck and Pileated Woodpecker remain two of my top three favorites of Audubon’s work, but were both edged out of first place the moment I saw what Audubon called the Carolina Parrot, which I consider the most touching and beautiful of all his work.

Audubon shot the birds he painted so he could get the fine details right. In the case of Carolina Parakeets, based on his writing, he kept a few in captivity for short times as well, making that illustration all the more poignant. The seven birds are not only interacting with one another and the cockleburs in the painting, but also the bottom central bird is looking directly into the artist’s eyes, and ours. I bought a print of that painting a few years ago at the Bell Museum.

Although I like knowing about early ornithology, it’s hard for me to read Audubon’s words. It’s a given that every early American ornithologist and, indeed, virtually every living ornithologist I encountered when I was in college, “collected” birds—their way of saying they killed them to study and to make museum specimens. It seemed ironic that the underpinnings of biology, the study of life itself, so depended on death, but none of the ornithologists I enjoyed talking to emphasized that—they really were consumed with bird life. Collecting was simply a tragic means to an important end.

In 1994 when I started work on my ill-fated Ph.D. program studying Common Nighthawk digestion under Gary Duke in the Avian Physiology Department at the University of Minnesota, I made it clear to him that I was not willing to sacrifice a single bird to answer my question about why nightjars had paired caeca where the large and small intestines meet. When I told him this, tears flooded his eyes, and he told me he was still haunted by his own graduate research studying American Kestrel digestion. He raised several baby kestrels knowing that he’d have to sacrifice each one at a different point in its development. As a sort of penance as well as a passion, he started rehabbing raptors in his own home and then, with his own graduate student Pat Redig, founded the University of Minnesota’s famous Raptor Center. So Gary was delighted to help me work out ways to prove or disprove my theory that an anaerobic bacterium in the caeca produces chitinase to help nighthawks digest the chitin in insect exoskeletons without hurting a single bird. We’d start by analyzing droppings produced after maintaining birds on different chitin-rich and chitin-free diets.

I brought one of my education nighthawks down to the University so we could feed her barium-laced food in a chamber to radiograph her digestive process. She was a perfect subject—calm and relaxed the entire time, and we got an amazing video recording starting while the food bolus was in her mouth and tracking it all the way through till she pooped the remains out. Tragically, unbeknownst to either of us, Gary was already suffering from early Alzheimer’s disease and lost the recording. It would have been so cool to publish the video and photos of that amazing process, but I at least got to watch it in real time. Losing Gary was the real tragedy.

Anyway, it never disturbed me that Audubon had to kill birds to paint them—what distressed me in reading his writing was how he seemed to relish the shooting, not just as a means to an end but for its own sake. Indeed, one of the most famous portraits of him shows him cradling his gun in a more intimate, protective way than photos of modern birders show us holding our binoculars.

As I learned more about Audubon’s life—how his family bought and sold enslaved people and how he led an escaped family to another enslaver—I thought I’d be happiest simply closing my eyes to everything about him except those three paintings I so loved.

But then Kenn Kaufman came along with his wonderful new book, The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness. I doubt that Kenn Kaufman has ever intentionally killed a bird, but he managed to capture Audubon in both his deep character flaws (which went well beyond what I knew) and his brilliance.

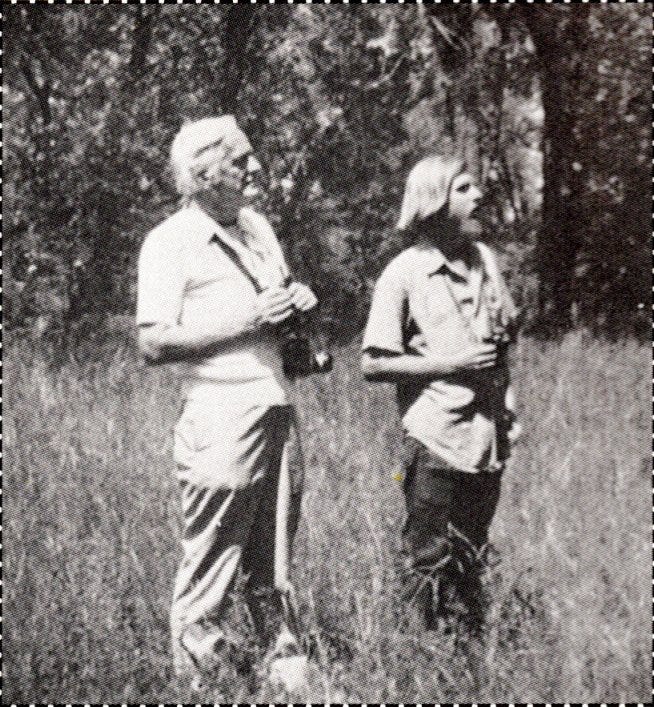

Like John James Audubon, Kenn Kaufman has been consumed with birds since early childhood. Indeed, of all my contemporaries (he’s three years younger than I), Kenn may be the most thoroughly consummate birder. He dropped out of high school when he was 16 to hitchhike across America seeing birds, and never lost that focused passion. In 1973, two years before I saw my first chickadee, he was setting a new record for the most birds seen in a North American Big Year. His splendid book, Kingbird Highway, a brilliant recounting of that year, was wondrously inspiring for me. (My 1999 review is here.)

I was particularly drawn to Kenn’s fearlessness. I’ve never hitchhiked in my life, but I think it was partly Kenn’s adventures that inspired me to set out on my own birding adventures, driving to and camping entirely alone in state and national forests, wildlife refuges, parks, etc. People say, “Well, you kept your car locked, right?” but no—one of the fondest memories of my life was sleeping alone in my sleeping bag atop my LL Bean air mattress in the back of my Prius at the Water Canyon Campground near San Antonio, New Mexico, during my own Big Year.

Not only was my car not locked—I had the windows and hatchback wide open so I could listen to a Flammulated Owl calling all night long. On my drive to Mount Washington in New Hampshire and Machias Seal Island in Maine that year, I noticed Lake Umbagog State Park on my map and made a detour simply because several species accounts of northern birds in the Bent Life Histories series mentioned Lake Umbagog. I camped alone there, too, this time with the hatchback shut tightly and the car windows barely opened a slit, but only because it was so cold.

My Big Year was done on a much smaller scale than Kenn’s—my 93-year-old mother-in-law had just moved in with us and we had to spend a chunk of the year’s discretionary income remodeling the bathroom to make it accessible. Her dementia made it impossible for Russ to travel with me at all, and also for me to be away for too much of the year. Kenn ended his Big Year with a total of 671. I broke 600 only by including some species, such as California Condor and Aplomado Falcon, that weren’t countable by the 2013 ABA rules—my official total was 595.

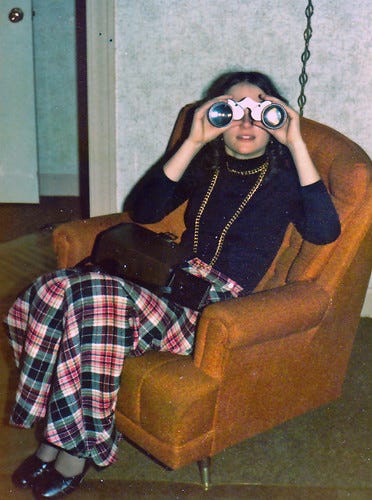

Unlike Kenn, when I was a kid, I never knew field guides existed nor that regular people could own binoculars. I was already married, with adult responsibilities, when I started birding in 1975—indeed, it was my husband who told his mom to give me binoculars and a field guide for Christmas 1974. When I daydream, I love imagining the freedom of being a carefree teenager living my passion.

Having been there, done that in real life, Kenn’s dreams extend much further back in time, to when so much of America was wilderness and the first white explorers were in a race to collect and catalogue every bird on the continent. For better and for worse, John James Audubon’s name is at the forefront of those early adventure stories. And Kenn, a thorough and insightful researcher and historian as well as an uncommonly engaging writer, manages to evoke the excitement and competitiveness of the era, and why it was so critical both to Audubon’s ego and his family’s financial survival that he be considered America’s premier authority on birds.

Kenn is clear about the ethical lapses, exaggerations, and even outright lying Audubon engaged in to establish and defend his artistic and scientific reputation, and also about the editing and erasing of much of Audubon’s written work, including his journals, by his granddaughter Maria, to burnish that legacy, making him appear less bloodthirsty and more aware of and concerned about disappearing species such as the Great Auk, Passenger Pigeon, and Carolina Parakeet, already on the road to extinction.

Kenn Kaufman is a wonderful artist in his own right—his work has been featured in several of his own books as well as at the prestigious, juried Birds in Art exhibition at the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum.

To get into the skin of Audubon without shooting any birds, Kenn tried his hand at painting birds in Audubon’s style. Like Audubon, he did a lot of field sketching, but he found that, like Audubon, those sketches weren’t enough to provide the intricate details of even the simplest-plumaged birds, even as Kenn was using high quality optics, something Audubon never had access to. I loved seeing what he did, in Audubon’s style, with some common birds that Audubon never knew existed, such as Western Grebe, Baird’s Sandpiper, Caspian Tern, Philadelphia Vireo, Swainson’s Thrush, and Kirtland’s Warbler.

I like to fall asleep reading on my Kindle. My review copy of Kenn’s book wasn’t electronic, but that was just as well—I’d have had a sleepless night, because the book was so engrossing: fascinating and timely, with my favorite subject, the natural history of birds, seamlessly woven throughout. I couldn’t put it down on my long flight to Key West last month—I was utterly absorbed. The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness is a clear-eyed and surprisingly exciting portrait of a time and place that have long ago disappeared, and an important and timely book as well. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

I am so happy to have your commentary in my life again. Thank you.