(Listen to the radio version here.)

One of the most beautiful gulls in the known universe is Ross’s Gull, which nests in the high Arctic of northernmost North America and northeast Siberia. (For one brief, shining moment, a small breeding population nested in Churchill, Manitoba; they were discovered in 1980 but disappeared in the 1990s.)

Ross’s Gull is not particularly uncommon in its breeding range, but is extremely rare south of the Arctic Circle, migrating only short distances south in autumn. The vast bulk of the population winters in northern latitudes at the edge of the pack ice in the northern Bering Sea and in the Sea of Okhotsk, but a few dozen vagrants have appeared here and there in the Lower-48 over the years, almost always in winter. I saw my first in Ashland, Wisconsin, on December 7, 2001. (I did a For the Birds program about that thrilling sighting here.) That’s also the last Ross’s Gull I ever saw until just this Saturday.

On May 31, Peder Svingen and Robbye Johnson reported one in non-breeding plumage at Wisconsin Point. I couldn’t get there for a couple of hours, and by then an eagle had spooked the birds from the beach far into the lake. I tried twice on Thursday but no luck, and I was gone to the bog on Friday. But when I arrived about 6:30 am Saturday, a host of birders were already looking at it, helping each of us newcomers pick it out among the Bonaparte’s Gulls and Ring-billed Gulls on the beach.

The first Ross’s Gull ever recorded in the Lower-48 was found in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1975. Hundreds of birders throughout North America and Europe flocked there to see it, making headlines all over the country. This event was credited with raising the profile of birding in the United States as birders discovered how many others shared their interest. That Ross’s Gull was called the “bird of the century.” This Ross’s Gull sparked something magical, too—the happy camaraderie of a bunch of birders enjoying such an extraordinary and beautiful sighting together. I was pleased that when I was enjoying it on Saturday, Peder and Robbye, the founders of the feast, stopped by again.

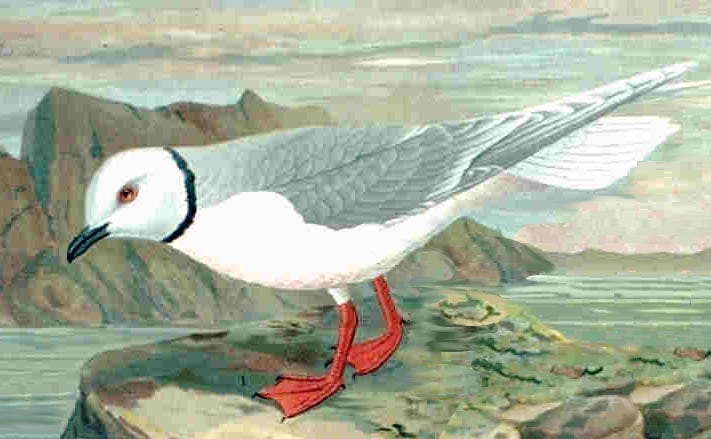

Ross’s Gull is the only member of the genus Rhodostethia, the name taken from the Greek rhodon for rose and stethos for breast. Its specific epithet, rosea, is Latin for rose-colored. Both elements of its scientific name pay tribute to its softly glowing pink breeding plumage, set off to perfection by a uniquely delicate black collar.

Ross’s Gull is tinier and paler than the Bonaparte’s Gulls our bird was associating with. Its much longer wings gave it a graceful, attenuated profile, and its tiny black bill enhanced its dainty appearance. It was almost perfectly white on the head, with a pale gray mantle. We were keeping a safe distance so we wouldn’t scare it off, so my photos are extremely cropped, but to have any identifiable photos of this extraordinary bird is something I’d never dared dream of.

In the water, Ross’s Gulls feed on fish and small crustaceans. On shore, they often feed on mudflats like shorebirds, as our gull was doing on the beach, picking through the wrack. During the breeding season, Ross’s Gulls are largely insectivorous, feeding on beetles and flies. They nest in small colonies on tundras and swampy Arctic estuaries, often in association with Arctic Terns, possibly because the extremely aggressive terns keep predators at bay. When wandering out of their range, they also associate with Arctic Terns or, like this lovely vagrant, with Bonaparte’s Gulls. I don’t know how long this one will stick around, and hope against hope that it’ll eventually find its way back to the Arctic, but I’m glad that while it’s so very far from home, at least it isn’t lonely.