Snail Kite

Triumphant return of an endangered species, for the wrong reasons

(Listen to the May 15 radio version here.)

One of the birds listed on the original Endangered Species List in 1973 was the Everglade Kite, found where native sawgrass was adapted for surviving hurricanes, periodic flooding, wildfires, and nutrient-poor soil. The kite fed almost exclusively on Florida’s native apple snail (Pomacea paludosa), which eats periphyton (a complex mixture of microscopic organisms) and mucky, decomposed matter called detritus. By reducing the decaying matter, this snail helps keep the water well oxygenated and the sawgrass and other native vegetation healthy.

Long before the Endangered Species Act was enacted, both the Everglades and the wildlife depending on it were in trouble. In 1948, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers started building a complex system of levees, canals, and reservoirs to control flooding along the Kissimmee River and Lake Okeechobee and to channel water away from farmlands and growing population centers south of Lake Okeechobee. What had been a vast natural river of grass was cut in half and enclosed into two “protected” areas, Everglades National Park and Big Cypress National Preserve, but they weren’t protected from channeling all that water away. And agricultural and suburban runoff infused nutrients fostering cattail growth at the expense of the sawgrass so essential to the Everglades ecosystem. Those nutrients also caused algal blooms on Lake Okeechobee, leading to periodic algal blooms on the coasts and in Florida Bay. To try to rectify this, in 2000, Congress approved a $10.5 billion project to send more freshwater into the Everglades.

There are signs of success, but meanwhile, an insidious new problem threatens the Everglades: saltwater intrusion due to rising sea levels associated with climate change. At first, aerial views showed large dead patches in the sawgrass where the salinity had killed the freshwater plants—one scientist said it looked like Swiss cheese. But now a plant that thrives in brackish and saltwater is taking root in what should be a vast freshwater wetland dominated by sawgrass. Mangrove forests have been destroyed all along the Florida coast and in the Keys in the name of development, so it’s ironic that such a splendid plant marks impending doom for the Everglades.

When I was on my birding tour to South Florida and the Keys last month, we spent a day in the Everglades with Michelle Davis, who spent decades studying the Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow—the only subspecies of the Seaside Sparrow who requires freshwater.

I longed for closeup views and maybe even photos on this trip to where the sparrows used to be common, but despite careful searching, only a few of us got a quick glimpse at a distant bird. We didn’t see a single Everglade Kite on the entire 6-day tour.

In 1988, my family spent a few days camping in the Everglades, and wherever we went, I focused on finding an Everglade Kite. I never found one in the park, but finally got a distant look at my lifer at what was considered the most reliable viewing spot, on the Tamiami Trail. I’ve been to the Everglades quite a few times since 1988 but have never again seen a kite there or anywhere in South Florida.

Yet every time Russ and I have visited our son in Orlando starting in 2005, we’ve seen at least one or two of these splendid birds, sometimes several, often at close range, at Kissimmee Lakefront Park, a busy urban park along Lake Tohopekaliga, and the adjacent Brinson Park, between the lake and a high-traffic highway.

The week before my South Florida birding tour, I was given an opportunity to bird in the Kissimmee area and sure enough, we saw lots of kites. We got especially close to them in a part of Lake Tohopekaliga I’d never been to before, on a boat tour from Toho Riverboat Adventures.

This company focuses primarily on tourists, not birders, but the captain was very familiar with the kites and made sure we had great looks.

We saw the kites from a bit further away on an airboat ride at a park called “Wild Florida.” The airboat captain was also very knowledgeable, bringing us to my lifer Gray-headed Swamphens the moment I said I’d never seen one. He also pointed out egg clusters of invasive snails so I could get photos.

The kite in Florida today isn’t what one could accurately call the Everglade Kite anymore. In the early 80s, scientists studying snail-eating kites throughout their range in Florida and Central and South America decided that these all belong to a single species, and the Everglade Kite’s name was officially changed to the Snail Kite in the Sixth Edition of the American Ornithologists’ Union’s Checklist of North American Birds in 1983. Some scientists still considered the Everglade Kite to be a valid subspecies, but others think Snail Kites are monotypic.

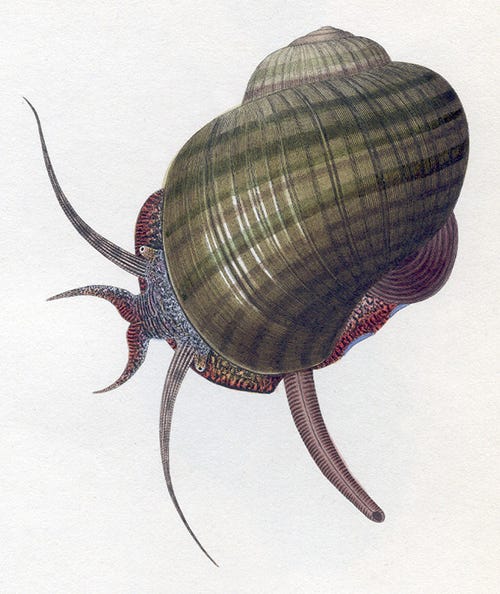

The only feature that made the Everglade Kite different from other Snail Kites was its shorter bill, designed specifically to pull the meat from Florida’s native apple snail, which is smaller than the apple snails of South America. Tragically, in recent decades, invasive apple snails from various sources escaped captivity in Florida and are now found throughout much of the state. Some of these snails feed on the living tissue of submerged plants, hurting native plants and making the snails economic threats where rice is grown. None of them belong in Florida, but it’s too late to close Pandora’s box.

Everglade Kites may have been specially adapted to eat the endemic snail but they’re functionally illiterate and never read that memo. In the early 2000s, when other species of apple snails suddenly appeared, the kites ate them, too. The kites with slightly longer-than-average bills had more luck than the others and produced more chicks. Like their parents, those chicks’ bills averaged longer, too, giving us a real-time look at how evolution works.

I’m old enough to have witnessed a lot of what we’ve lost in the Florida Everglades, but not nearly old enough to have seen it at its best, before our species decimated nesting wading birds for the feather trade, changed the entire course of freshwater flow in the Florida peninsula, and spewed so much fertilizer and pesticides into the water. Burmese pythons, feral cats, and now exotic apple snails have exacted a heavy toll. Some birds, like the Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow, will probably never recover, especially now that rising sea levels are wreaking a different form of havoc on the Everglades.

I’m heartbroken that Snail Kites will never find the Everglades the haven it once was for them. But I’m delighted that this splendid bird is making the best of a bad situation. A world without Snail Kites would be a dark world, indeed.