(Listen to the radio version here.)

I woke up early on May 11, 1975, filled with anticipation. Spring migration was at its peak. Two days before, I’d seen my first Baltimore Oriole, bringing my life list up to what felt like an amazing 26 species—I never imagined I could see so many different birds in one season! I’d been too busy with classes, homework, and my part-time job to bird on May 10, but now I was headed out with my binoculars, field guide, and field notebook, hoping to luck into yet another wonderful new bird.

Right off the bat, in the shrubby open area near the railroad tracks between the MSU Natural Resources Building and Baker Woodlot, I heard a distinctive call—a sound I’d never consciously heard before, but one that so clearly could be described as mewing that I instantly thought this must be a Gray Catbird! The bird was tucked deep into the shrubs, but I scanned every branch I could see, taking my time, and voila!

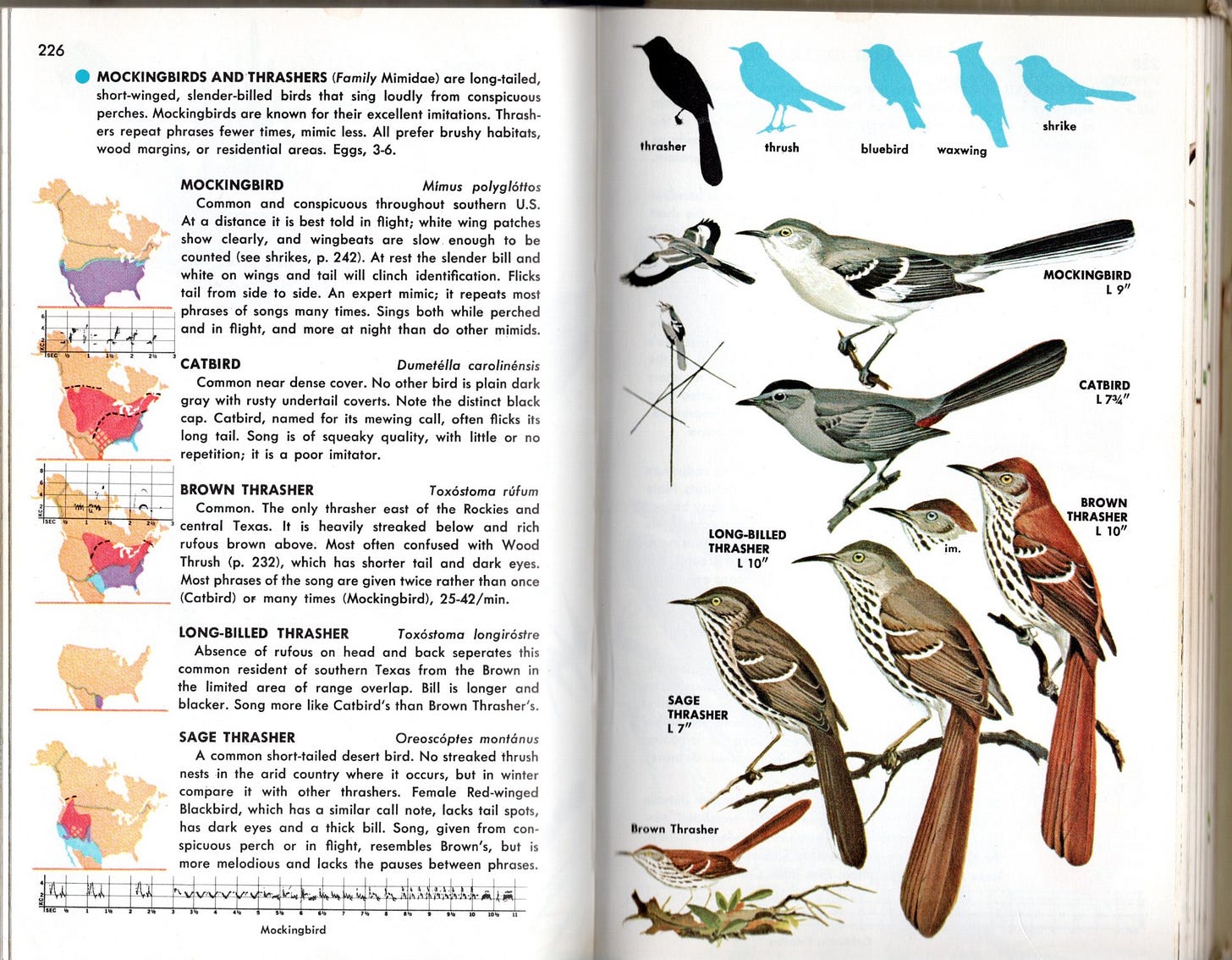

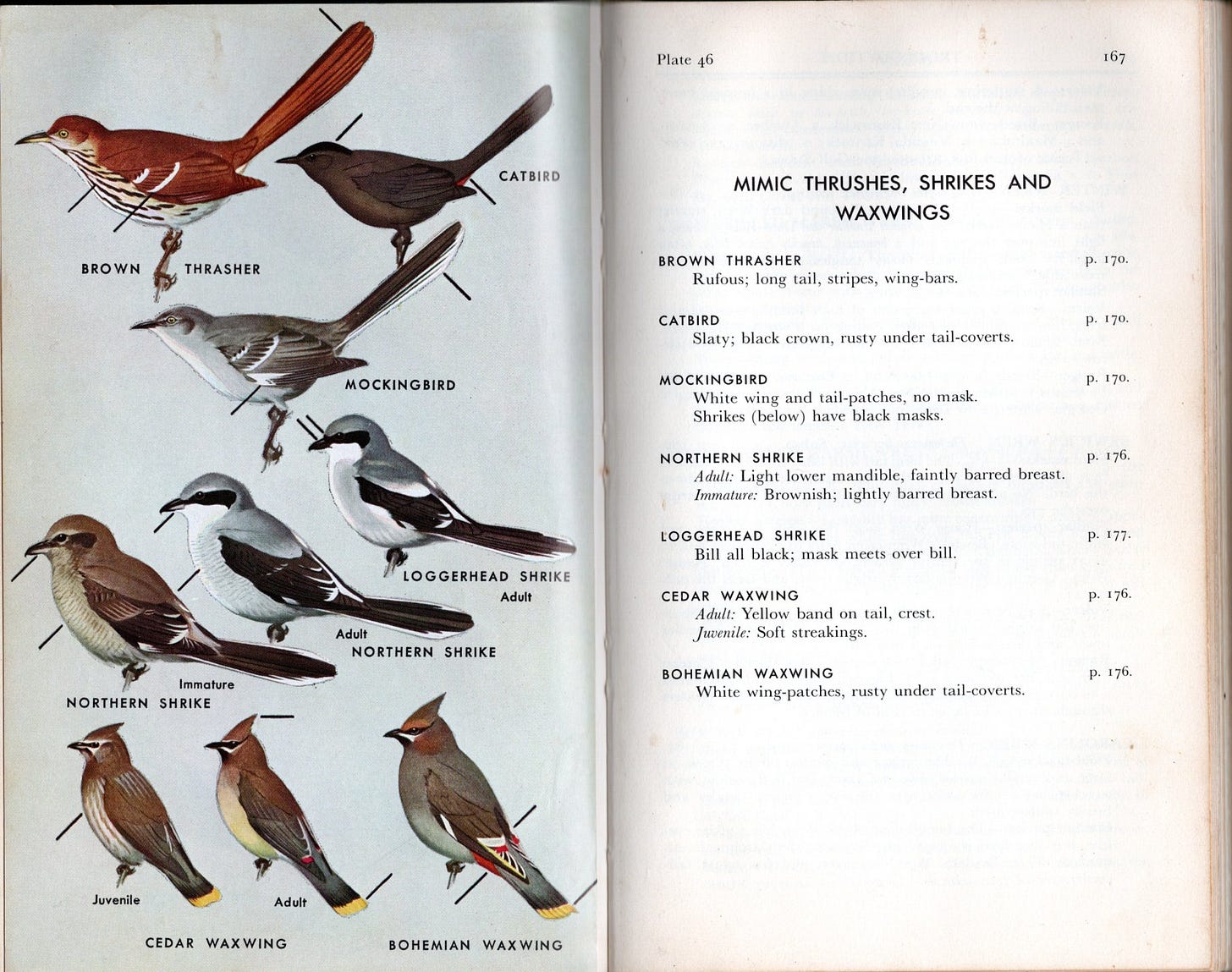

To count any bird as a lifer back then, before I knew how to take in a bird’s gestalt, I had to see every single feature pointed out in the field guide. My Golden Guide said: “No other bird is plain dark gray with rusty undertail coverts. Note the distinct black cap.” It also mentioned that it “often flicks its long tail.”

The moment I saw the bird hiding within the foliage, I could see that it was pretty much solid gray, and maybe a second later, I saw the black cap. But it flitted away before I could see the rusty undertail feathers. I picked up on it again when it alighted at the top of a bush and flicked its tail, but the angle was wrong, and again it flitted out of sight.

But I was bound and determined to see this bird’s private parts. It took at least five minutes—maybe ten—but my persistence was finally rewarded.

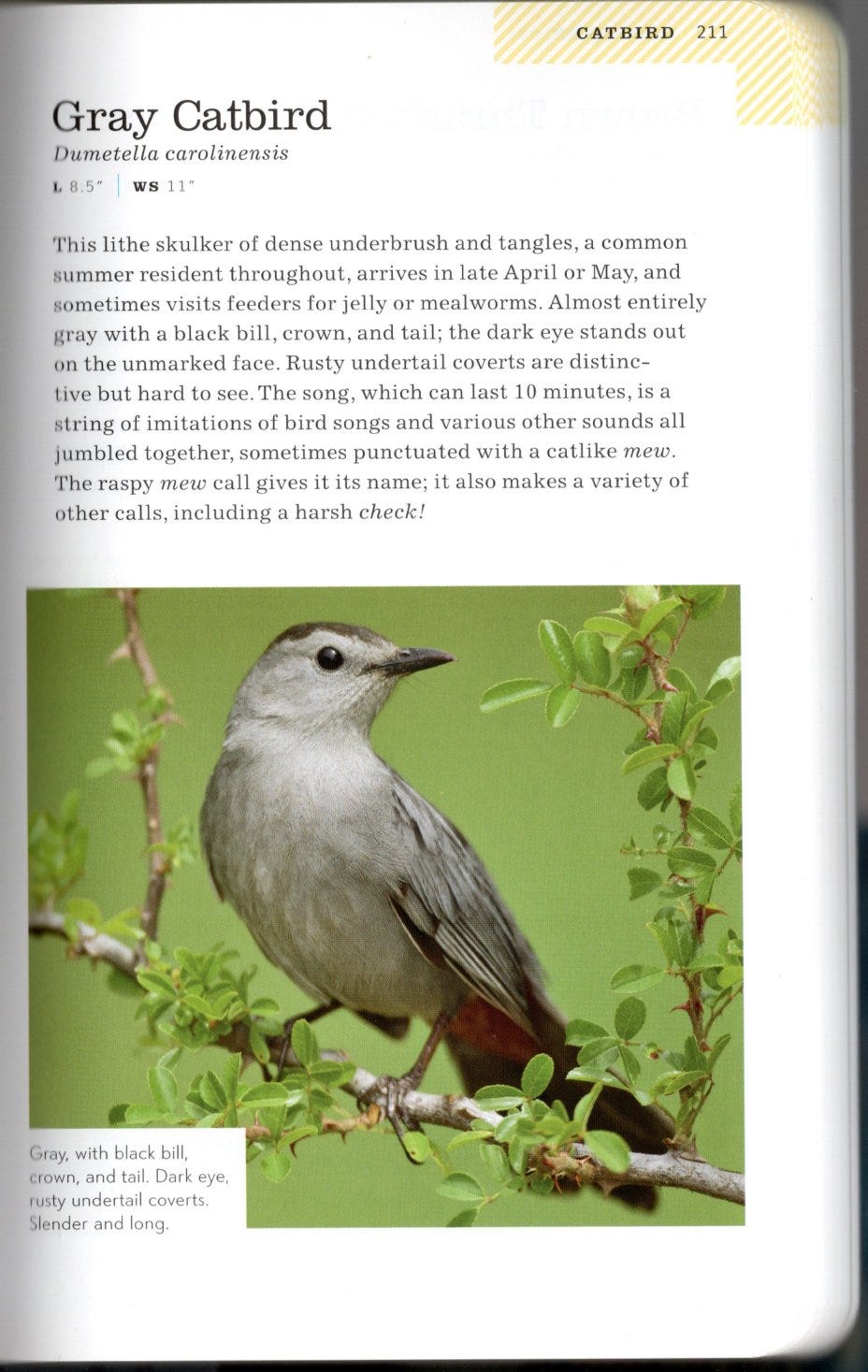

Meanwhile, as I was searching for that one feature, I was taking in the bird’s slender shape, which gave it a handsome gracefulness accentuated by its large black eyes and slender black bill. The sheer elegance of this bird took my breath away. I was in love.

That first year, I always looked up any new birds I saw in my Peterson Guide when I got home. Peterson’s trademark “Peterson system” lines pointed directly to the black crown and rusty undertail coverts. His description in the text section read: “Smaller and slimmer than a Robin; slaty-gray with a black cap, and with chestnut-red under tail-coverts (these are seldom noticed in the field).”

But, rank beginner though I was, I had really and truly seen that hidden feature! I was very proud to have found and identified, all by myself, # 27 on my life list. Ever since that triumph, I’ve tried to see the undertail coverts every time I see a catbird. This habit keeps my eyes on these elegant birds a little longer than on most other species, but when the bird is this dainty and special, that’s a feature, not a bug.

In my own American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Minnesota, I wrote “Rusty undertail coverts are distinctive but hard to see.”

This summer I’ve had a pair of catbirds visiting my yard many times a day. I know they’re nesting somewhere nearby because for a few weeks, I saw them carrying caterpillars, and have also seen fledglings.

I don’t like paying too close attention to nesting birds unless the nest is in a very obvious place and is reasonably secure—like a chickadee or woodpecker cavity—because the Peabody Street Blue Jays and crows often keep track of what I’m doing. I’d hate to tip them off to a nest!

Anyway, over two weeks ago now, one of the catbirds must have gotten into a tussle with a predator or got caught in something and lost its entire tail. Anyone looking at this bird could not help but see those undertail coverts. Of course, it’s now missing the long tail it’s supposed to be flicking, so I’d have had a lot of trouble figuring out what it was if I were seeing it as a beginner.

I of course took a bazillion photos, including some of it carrying food, presumably to feed babies.

It was fun to see and photograph it, but now I’m suddenly starting to worry. Over the years, I’ve tracked a lot of birds who’d lost their tail feathers. If the feathers break off, the bird must wait until the next molt to replace them. But if the feathers are torn out at the root, new feathers start growing in immediately, so within days I should have been seeing a little stub, and by now, there should be an inch or two of tail. But as of July 31, I don’t see any evidence at all of emerging feathers.

This is clearly not impairing the bird’s day-to-day activities, and its mate seems just as accepting as before the tail disappeared. But I’m concerned about how it’ll fare when it migrates if it still doesn’t have a tail in a few weeks. Maneuvering to elude unexpected obstructions is more difficult without a tail to help steer. It’s getting lots of practice now, but only for fairly short flights. As nocturnal migrants, catbirds are very vulnerable to collisions with lighted structures—in five of eight North American regions where communications tower mortality was quantified, the Gray Catbird was among the ten most often killed at towers. That has nothing to do with their tail feathers, of course, but it still makes me worry.

It’s so wonderful to be able to track individual birds, but scary, too—suddenly I’m invested not in catbirds as a cool and elegant species, or in the generic catbirds in my yard, but in one individual catbird.

Catbirds are doing very well in Minnesota and over their entire range, according to Breeding Bird Survey data and the Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas, and an Audubon study of how different bird species would fare under a few different climate change scenarios determined that the Gray Catbird is expected to have minimal disruption throughout its range. So losing one catbird won’t mean anything at the population level, and because this bird seems to have produced young this year, its genes should live on. That’s small consolation, so I’m going to cling to hope, even if in this case, hope is the thing without tail feathers.

A very exquisite study of the "Gray" Catbird and useful, wise notes comparing field guides. Perhaps future guides could be more dramatic showing the underside of birds as well like the photographic Warbler Guide, the only only I'm aware of that does. It would be neat, and I feel it would be useful, though I suppose there are those that would disagree. Your photographs, by the way, compliment your blog posts well.