The Material Realities of Biological Sex

Birds don’t ostracize individuals from their social flocks based on “objective sex-based differences.” That would undermine their civil society.

(Listen to the radio version, Part 1 here and Part 2 here.)

On Sunday, I received an email from Bruno, a podcast listener in Alberta, who wrote:

Thank you for your engaging podcast episode, “Hey! My eyes are up here!” from *For the Birds* on May 29, 2025. Your reflections on the remarkable qualities of birds and their natural acceptance of individuality offer a compelling contrast to human behavior. Having listened to your podcast for several years now, I deeply appreciate your celebration of the unadulterated beauty of the natural world.

However, I am concerned about the (albeit brief) promotion of pronouns as a means of defining identity, as it often aligns with gender ideology that I believe undermines biological reality and civil society. Your podcast focuses on birds, which recognize each other as individuals without the need for constructed social markers like pronouns. From a non-genderist perspective, emphasizing pronouns in any context risks reinforcing a framework that prioritizes subjective identity over objective sex-based differences, which can erode protections for women and girls and dismiss the material realities of biological sex. I worry this trend could lead to further confusion and division in society, particularly when it comes to single-sex spaces, fair treatment, and the treatment of vulnerable youth and adults.

I’d be interested in hearing your thoughts on how the natural world, like the birds you so eloquently describe, might inform a perspective grounded in biological truth rather than subcultural constructs. Thank you for your thought-provoking work, and I look forward to more episodes celebrating nature’s clarity and wisdom through bird life.

My only reference to pronouns in that episode was this: “Except during mating, the sex of most birds doesn’t matter to them anyway—they’d be perfectly content using they and them as their pronouns.”

I stand by that. We don’t understand bird language, much less its grammatical structure, so my use of the word pronoun is a stretch, but the biological truth is that during most of the year, for most of the species I watch, one another’s genders are completely irrelevant in their behaviors, interactions, and how they treat one another.

The concept of “single-sex spaces” is pretty limited in the world of birds. The only exception I’m familiar with is the Wild Turkey. In winter, the large, aggressive adult males stay together while the smaller females stay, with the young of the year, in their own flocks. As young males grow large, they leave and join the adult males.

Unlike mammals, birds do not have XX or XY chromosomes. Birds who produce sperm have ZZ chromosomes and those who produce eggs have ZW chromosomes. Almost all female birds have a single functional ovary on the left side, the right one shrinking during embryonic development (probably to reduce weight for flight), and females ovulate only during their nesting season. For a good eight or nine months each year, female birds of most northern hemisphere species aren’t at all concerned with sex or gender.

The same is true of most male birds. Their two testes shrink after the breeding season, remaining small and producing very little testosterone through most of the year.

Some species, especially those who pair for life and share nesting responsibilities fairly equally, show little or no discernible sexual dimorphism, and in many of the species in which males do look very different from females during the breeding season, the males molt into more female-like plumage as soon as nesting is done. Again, outside the nesting season, the sex of birds is pretty much irrelevant in their day-to-day activities and interactions.

Depending on the species, mate selection (not the act of mating) happens in fall, winter, or spring before the birds are physically capable of reproduction. In flocking species in which mated pairs remain together throughout the year, such as Sandhill Cranes, Canada Geese, and chickadees, the only flock members who seem at all focused on gender are those still seeking a mate, and even those individuals are more immediately concerned with issues of day-to-day survival. Members of bird flocks can’t afford to judge or exclude flock members—they need each other to help them detect predators and find food.

We learn as very small children that there are two sexes, but one of my favorite birds, the White-throated Sparrow, throws that concept entirely out the window—some experts say this species essentially has four sexes! White-throated Sparrow plumage comes in two color forms—some have dull tan head stripes and some have bright white ones.

Intuitively, we might think the males are the ones with the bolder white stripes, but nope—50 percent of all males have tan stripes, and 50 percent of all females have white stripes. Yet a full 98 percent of all mated pairs have one tan and one white striped member. Apparently, mate selection for them involves choosing a bird of both the opposite chromosomal sex and the opposite head-stripe color. After the breeding season is over, the birds spend fall, winter, and spring in sociable flocks where neither sex nor head-stripe color seems to matter at all.

During the nesting season, some species have strictly defined sex roles. One or the other may have the primary responsibility for claiming and defending the territory, nest building, incubating eggs, brooding nestlings, hunting for food, and feeding nestlings, but how pairs divvy this work varies widely among species. In many species, the male and female share each or most of these roles equally.

Regardless of whether sex roles are strictly defined or not, they’re only pertinent during the nesting season which, again, is just a fraction of most birds’ annual cycles.

Individual variation exists in all species of plants and animals, and some naturally occurring individual birds do not fit into any male-female dichotomy. Going back as far as Aristotle, we've known that some individual birds, most noticeably among ducks and chickens, are intersex, a naturally-occurring condition that sometimes happens to a bird with ZW chromosomes (i.e., a “female”) if her only ovary stops functioning. As the hormones produced by the ovary dwindle or disappear, the hormones associated with her Z chromosome may cause her to molt into more male-like plumage, and her behavior may change as well. Some intersex Mallards (chromosomally female) have been recorded mounting females, and some allow males to mount them, even though without a functional ovary, they cannot ovulate to produce eggs. Intersex ducks can be well integrated into Mallard flocks, as was one I photographed in Ithaca, New York, in 2009.

Many of us at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology watched that individual over the entire winter. I lost track when the flock dispersed during spring migration.

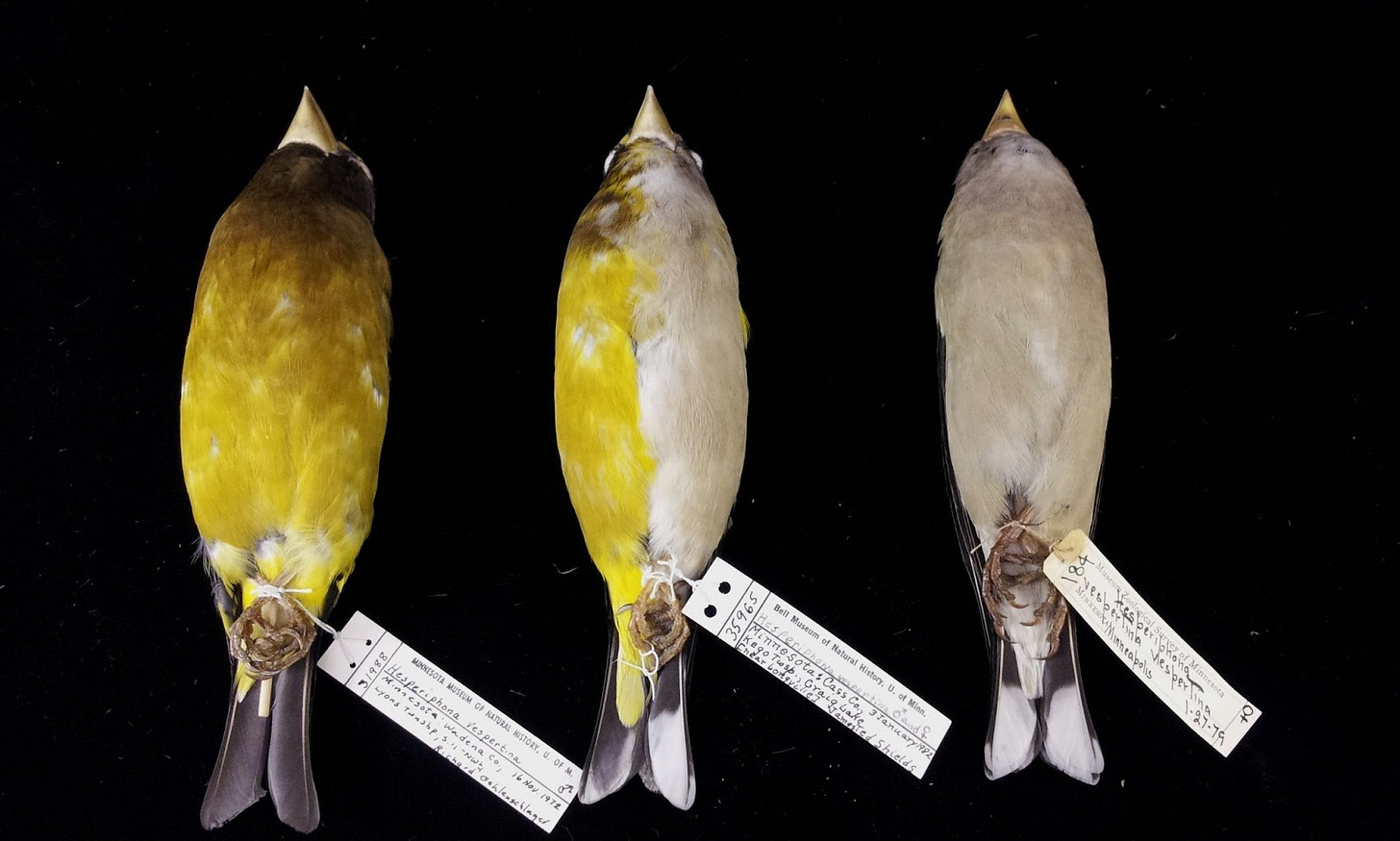

Another interesting situation of gender identity in birds—one in which the pronoun they would be far more biologically accurate than either he or she—is that of gynandromorphism. Gynandromorphic birds are literally half and half, one side of the body with a functional ovary, the other with a functional testis. In bilateral gynandromorphism, the bird's body plumage appears male on one side and female on the other, and the wing chord measurements may also differ. Gynandromorphism would be essentially impossible for us humans to detect in the field in species without obvious sexual dimorphism because the sex organs themselves are internal, but the condition has been described in more than 40 bird species. The University of Minnesota's Bell Museum bird collection includes a handful of gynandromorphic Evening Grosbeaks.

In 1986 during the height of fall migration, I happened to see a gynandromorphic Evening Grosbeak within a big flock pigging out on the platform feeder attached to my dining room window. I watched them at very close range for a good five minutes. (Sadly, this was before I was photographing birds.) The gynandromorphic bird’s left side appeared to be in perfect adult female plumage and its right side almost perfectly adult male, though on that side the tail was paler and the forehead not quite as black as on nearby adult males. Unfortunately, when a hawk flew past, they all scattered in a flurry of wings, and I never saw that one again. (The hawk didn’t catch any of the grosbeaks that time around.)

In the five minutes I watched it, I saw that the gynandromorphic Evening Grosbeak was perfectly integrated into the flock, feeding close to the center, neither isolated nor pushed off to one side. Grosbeaks occasionally squabble to defend their “body space,” but the gynandromorph wasn’t involved in any more squabbles than the others. As far as I’ve ever seen, birds don’t ostracize individuals based on “objective sex-based differences.” That would undermine their civil society.

Humans, of course, are different from birds. From what I have observed in my 73 years on this planet, bad and unfair treatment of women and of vulnerable youth and adults comes from those people who don’t understand biological reality, don’t recognize how important diversity is in ecological systems and within species, and don’t understand that our acceptance of the many individual human beings sharing our schools, workplaces, neighborhoods, recreational facilities, and larger environments is fundamental to maintaining a civil society. Perhaps birds could show us the way.