(Listen to radio version of the first half of this post, about the Breeding Bird Survey, here, and to the second half, about weather radar data, here.)

In 2015, I went to the emergency room suspecting a heart attack. A whole team of doctors, nurses, and technicians appeared like magic and rushed me into a nearby room where they put me on a bed and set to work. One took my blood pressure, another drew blood, and another hooked me up to an EKG. My blood pressure was way higher than normal for me, and the nurse taking it started to reassure me that the fear of a heart attack and going to the ER can cause that, but the guy reading the EKG interrupted. “Nope. This is a real heart attack!” (Spoiler alert: I survived.)

The blood draw tested for troponin, a protein released when heart tissue is damaged, which would confirm a myocardial infarction and determine how much damage had been done. I stayed in the hospital a couple of days, and before they released me, they did another test—an echocardiogram. That confirmed the cause of the heart attack—an aneurism, probably congenital, on the right coronary artery. This was a simple, straightforward diagnosis, but it took at least four separate tests to reach it and get to the root of the problem.

Assessing what is happening with bird populations is much more complicated, but like diagnosing a heart attack, different tests reveal different information.

The first good test we had for seeing trends in bird populations was developed by Chandler Robbins. This quiet, unassuming scientist at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service worked closely with Fish and Wildlife Service writer and editor Rachel Carson in the 1950s as they both grew increasingly alarmed about the effects on birds of pesticides and other pollutants. After Silent Spring was published in 1962 to a barrage of vicious personal attacks on Carson, one of the common responses by critics of her work was that there was no proof that bird populations were declining anyway, so Robbins created a system for monitoring the status and trends of North American bird populations—the Breeding Bird Survey.

That project still provides essential data about bird population trends, but like blood pressure or an EKG, the Breeding Bird Survey can’t tell us the extent or root causes of the problem. BBS data includes only singing birds on territory, with no way of tracking how many “extra” birds, or floaters, may be waiting in the wings for a territory holder to disappear so they can jump in.

In his 1945 textbook, Modern Bird Study, Ludlow Griscom wrote:

An acquaintance of mine made a very interesting but somewhat cruel experiment some years ago with the Indigo Bunting. Finding a nesting pair near his house, he proceeded to shoot the male. The next day, the female had secured another male that sang in the same territory claimed by the first mate. He proceeded to shoot the second male. This kept on until he had shot nine different male Indigo Buntings, and he left the tenth male to help the female raise her family.

Griscom wrote that this experiment suggests that “there are a larger number of un-mated birds wandering around the country in the breeding season than ordinary observation would lead one to suspect.” If that study were conducted on a Breeding Bird Survey route, the BBS results would have shown exactly one Indigo Bunting on the route until every one of those ten males, and maybe even more, was gone, and at that point it would show a loss of just one bird. As long as habitat quality remains the same, you can lose an awful lot of individuals before any loss is detected via the Breeding Bird Survey.

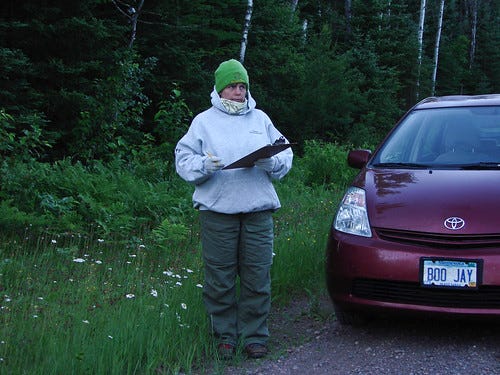

Chandler Robbins selected the original Breeding Bird Survey routes randomly, but as more and more pristine habitat is developed and roads become noisier and more dangerous, little by little the routes have been changed to ensure the safety of the volunteer counters. Necessary as this is, it skews the results, often making it appear that birds haven’t declined where they have. In the 20 years I conducted a Breeding Bird Survey, my route near Brimson was changed three times as more houses sprouted up, increasing traffic. The changes artificially maintained higher numbers of warblers, thrushes, and other forest birds and kept down the numbers of starlings, grackles, cowbirds, and other backyard birds that took over the damaged habitat along my original route. Like measuring blood pressure, the BBS can suggest serious problems, but we need a lot more information to know exactly what is going on.

As long as habitat quality remains the same, you can lose an awful lot of individuals before any loss is detected via the Breeding Bird Survey.

A second important tool for assessing population declines was used by Sidney Gauthreaux of Clemson University, one of the first scientists to figure out that bird migration is visible on weather radar. Radar can’t identify birds by species but does provide a good look at the magnitude of migration, providing gross numbers of individuals of general size categories flying over a given place at a given time.

Looking at archived radar images, Gauthreaux found that movements of migrating birds over the Gulf of Mexico had dropped by almost 50 percent between the 1960s and 1980s, and by another 50 percent in the following two decades. Some of his analysis was almost certainly imperfect, as every scientific study is, and depended on the less nuanced radar before NEXRAD, the “new generation” Doppler radar was developed, but his work provided powerful evidence that birds were declining much more rapidly than Breeding Bird Survey data suggested.

Even though Gauthreaux was acclaimed for his pioneering work, some prominent conservation biologists disputed and even pooh-poohed this major study. Like the ER nurse who tried to reassure me that my elevated blood pressure was “probably nothing,” these scientists’ primary tool, the Breeding Bird Survey, didn’t show the magnitude of loss Gauthreaux’s data did. Unlike my nurse, who immediately accepted the EKG results, these scientists harshly criticized Gauthreaux for being too “alarmist.”

I quoted Gauthreaux’s work in my 2006 book, 101 Ways to Help Birds, which was panned by some of those same conservation biologists: Not only was I being alarmist, but my 101 ways focused on issues they dismissed at the time as “trivial,” such as cat predation, window collisions, too much beef consumption, mowing pastures during nesting season, and our driving habits; their work focused on habitat loss. I hardly disagreed with them about the importance of habitat on breeding, wintering, and migratory ranges, but knew that other important issues were also harming birds by the millions and even billions.

Gauthreaux’s work provided powerful evidence that birds were declining much more rapidly than Breeding Bird Survey data could suggest.

A growing understanding of how to interpret weather radar, along with the development of modern Doppler radar, revolutionized the study of bird migration, making it possible to monitor even more closely the movements of birds through the atmosphere. Now conservation biologists include it in their arsenal of approaches to detecting bird population losses. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Colorado State University, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst have even developed a website, BirdCast, which forecasts bird migration movements based on radar information. It’s invaluable for birders—we love knowing ahead of time the best days to get out there to look for newly arriving migrants. More importantly, conservationists involved in various lights-out programs can inform the public to turn lights off on major migration nights to protect nocturnal migrants from the very collisions so many scientists had once dismissed as trivial.

eBird is also an important tool for assessing population trends. Like my echocardiogram, eBird provides nuanced information that can reveal how bird movements and numbers are changing over time, helping diagnose the problems birds face. eBird’s value will keep increasing enormously over time as more and more birders contribute their data. Next time I’ll focus on the important, nuanced scientific information eBird is already providing.