The Value of eBird, Part 4

Science! Conservation! Education!

(Listen to the radio version here.)

(Go Birding with the Times! Read about the eBird challenge, a collaboration between The New York Times and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology here.)

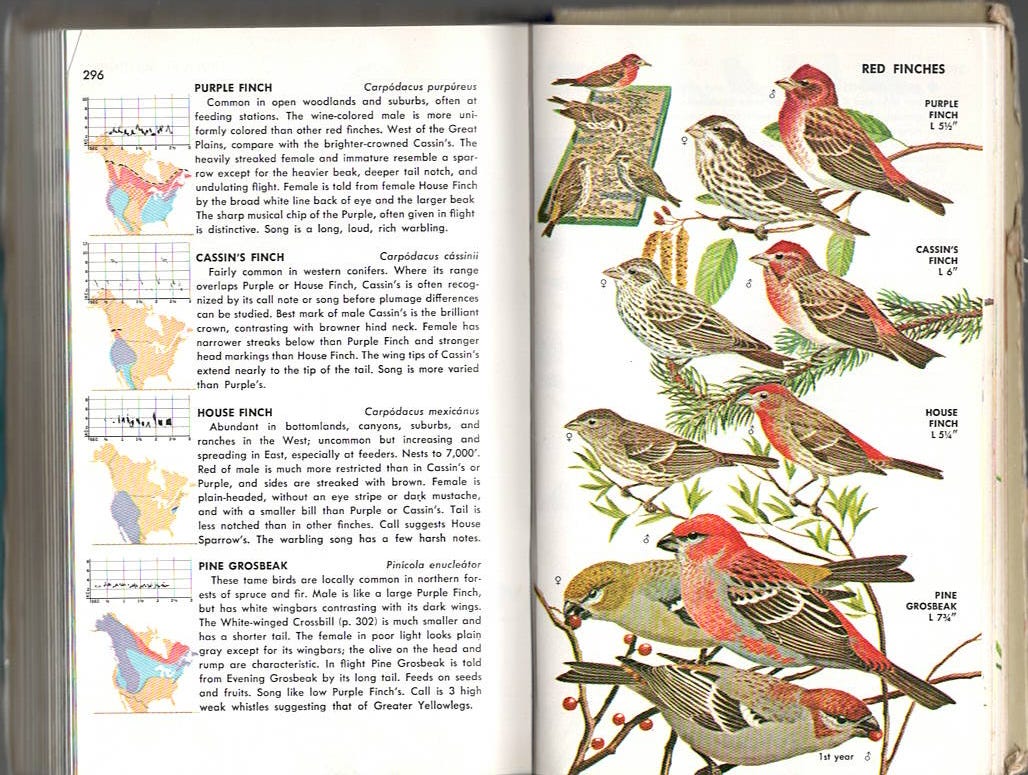

The House Finch was originally a bird of the western United States and Mexico. My Audubon Land Bird Guide, published in 1949, focused on eastern species but did include the House Finch without mentioning that in 1939 or 1940, a small number of them had been released from cage bird distributors on Long Island, New York. Audubon Land Bird Guide author Richard Pough had to be aware of that as he wrote the book, so he deserves credit for including them for East Coast birders, but he had no way of knowing how well these “Hollywood finches” would thrive in the East. Within the next 50 years, they had spread across almost all the eastern United States and southern Canada.

The Golden Guide, published in 1966, showed the eastern range as just a tiny dot on the East Coast. By the time the second edition came out in 1983, the range had expanded greatly, the map showing it extending almost as far west as Wisconsin.

T.S. Roberts wrote in The Birds of Minnesota that a male House Finch, either a long-distance vagrant or an escaped captive bird, was shot by Robert McMullen in Minneapolis in 1876. The next observations of House Finches in the state were in 1971 and 1972, but in both cases, there were no photos and the written documentation was not strong enough to rule out the much more likely Purple Finch, making the records tantalizing but questionable. The next House Finch record was well documented but again without confirming photos, in the Twin Cities in 1980. Then in 1983, another one was both well documented and photographed. After that, records snowballed; by 1992, House Finches had been recorded in 80 of the state’s 87 counties.

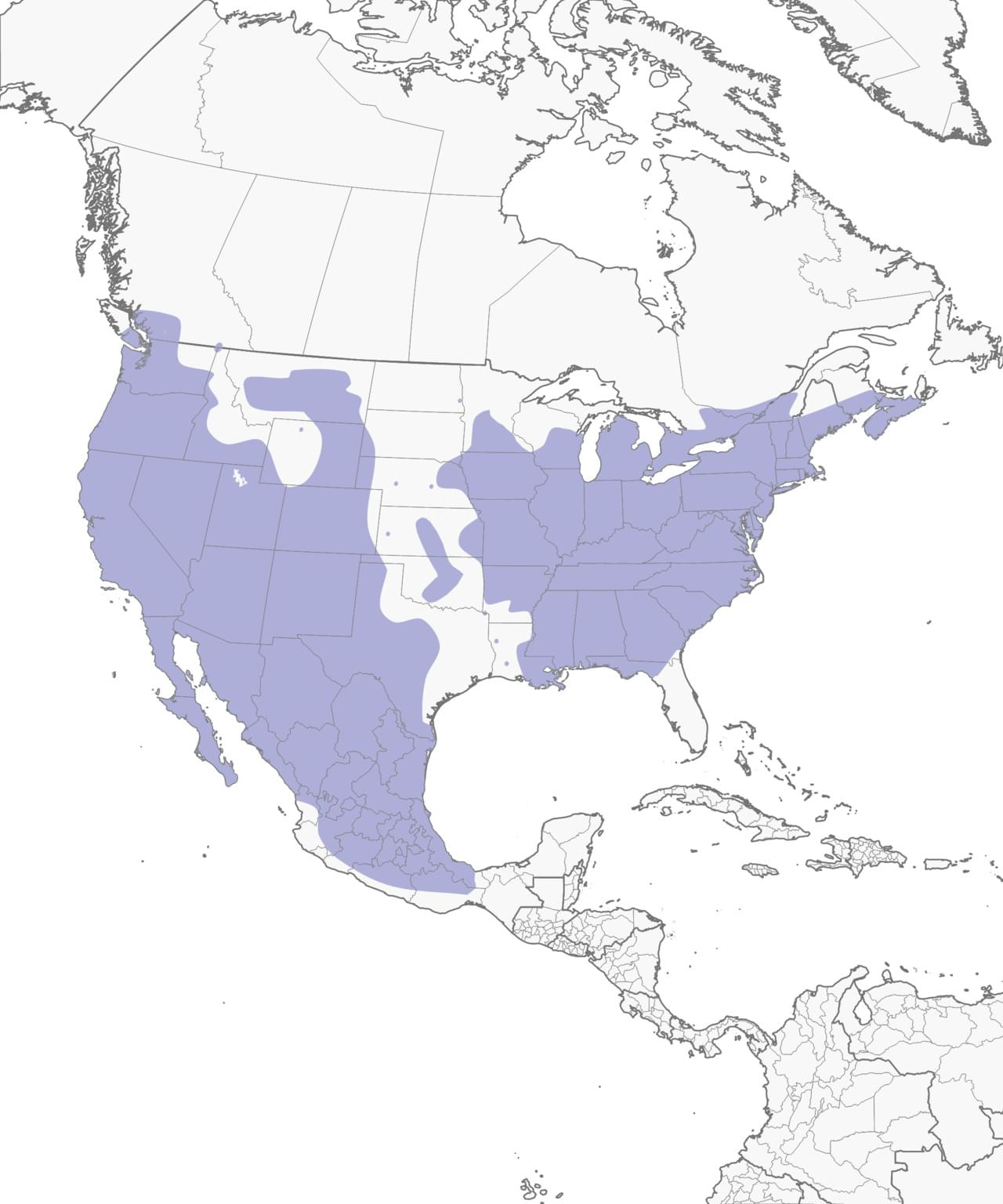

Trying to find a current range map of the House Finch, even online, can be tricky—even the map on Cornell’s All About Birds website shows the western range and the eastern range still separated in the middle.

The one map you can count on being accurate and current is eBird’s, powered by eBird data and updated annually.

eBird provides scientists, conservationists, educators, and the rest of us with high-resolution data, visualizations, and tools describing where bird populations occur and how they change through time. Thanks to the birders supplying data to eBird, and to the volunteer reviewers ensuring that data is accurate, conservationists can rely on it for monitoring and managing populations, protecting habitat, and informing law and policy.

Had eBird been available in 1971 and those Minnesota House Finches entered in the database, the report would have instantly alerted birders to check it out, perhaps providing either corroboration or a correction. And the eBird reviewer would have asked for more details, possibly while the bird was still present for the original reporters to have added salient details.

In the fall of 1991, Peder Svingen found a Fork-tailed Flycatcher at Erie Pier in Duluth, jotted down his important notes and rushed to get to a phone to alert Kim Eckert. Kim called me, and the two of us were both there within 20 minutes, but this bird, the first Fork-tailed Flycatcher ever reported in Minnesota, was gone with the wind, and neither Peder nor anyone else managed to locate it again. It was officially entered into the Minnesota records not because Peder is well known to be a great birder or because people on the committee liked him (though both were true) but because of his careful documentation. The very next spring, a Fork-tailed Flycatcher appeared in Grand Marais and remained in the same spot for many days. I saw that one, though this was well before I had a camera suitable for bird photography.

Now that digital photography is so very accessible to so many birders, most rarities entered in eBird get photographed, by the original poster and/or others checking out the report. I took photos of the Fork-tailed Flycatcher reported by Adam Sell on Stoney Point this past September 17—that bird was there long enough for people in Duluth responding instantly to get there in time to see it before it flew the coop.

On October 29, when I got word that a Phainopepla was being seen near the McQuade boat landing, I rushed right over. That one stuck around until November 1. Many of us photographed it and I got a good sound recording.

States and provinces keep records of rarities and the arrival and departure dates for regular migrating birds. But their data isn’t easily available to people in other states and provinces, and melding the data from every state and province is unwieldy. That’s why even when people report such species as Evening Grosbeaks to their state organizations, it’s important to also report them on eBird, so we can see continental patterns when these irruptive birds appear here and there in unusual numbers. Most state records committees now accept eBird records directly, so people don’t have the burden of making two reports.

In another 50 years, will Fork-tailed Flycatchers or Phainopeplas be appearing regularly in Minnesota, as House Finches are now? How will Evening Grosbeaks be faring? Will the smattering of records of Eastern Screech-Owls in Duluth become more regular? It’s impossible to know. It’ll be the reports and documentation on eBird that allow us to track these birds in real time.

This summer, The New York Times is collaborating with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to promote eBird via the eBird challenge, “Go Birding with the Times.” Summer is when many birders take a break from birding between the two migration seasons, but data from the breeding season is extremely valuable, even just from our own backyards and neighborhoods. Please check it out and participate!