(Listen to the radio version here.)

When I was a little girl, I’d have given any of my teeth (especially before my permanent teeth came in) to have a book that showed all the birds I could possibly see in Chicago. Oddly enough, I didn’t know there was such a thing as a field guide until I was in college, but I know that if I’d seen one as even a very young child, I’d have been enchanted and maybe even obsessed with it.

I suspect that’s because none of the adults in my life recognized birds except pigeons, robins, and cardinals. Ducks were ducks and sparrows were sparrows. My mother called what I later learned were grackles “crows.”

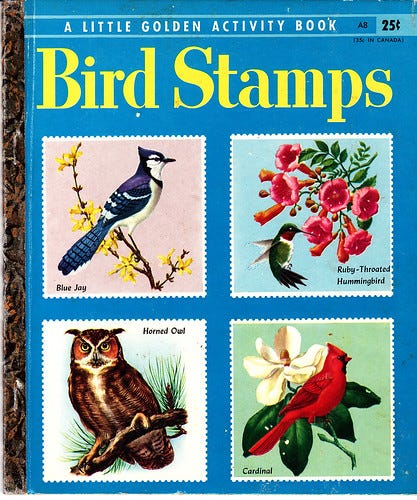

I did know Blue Jays existed thanks to Bird Stamps: The Little Golden Activity Book, a book my Grandpa gave me when I was 4 or 5, but had no clue that anything as cool as a chickadee existed.

Yet I can’t remember my own children ever once cracking open a field guide on their own. If they noticed an odd bird in the yard, they told me about it, I told them what it was, and that was that. As much as they enjoyed helping me with individual birds when I was a licensed rehabber, and as much as they searched out birds I wanted to see on all our family vacations, they weren’t interested in birding themselves. They somehow decided, probably not even consciously, that birds were my province. We always planned our family vacations to accommodate my birding, but we also spent whole days doing things everyone else chose.

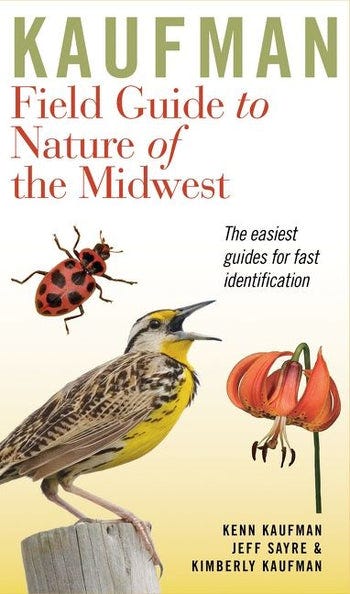

I strongly believe that when children of any age ask the fundamental question, “What’s that?” we have an obligation, if we don’t know the answer, to show them how we find out. That’s why I think every home should have at least one good field guide to birds, and field guides to other natural phenomena, such as mammals, reptiles and amphibians, insects and other arthropods, trees and shrubs, herbaceous plants, lichens and fungi, and the night sky. Every household in my neck of the woods—that is, the Midwest—should have a copy of the Kaufman Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest, which covers an incredible and well-considered array of all this and more.

Toddlers may not be interested, but this book will help parents and older siblings to answer toddlers’ and their own questions. The Merlin and iNaturalist apps do a fairly good job of identifying birds and other animals and plants, but books are much more valuable because children can page through them long before they’re old enough to be playing with cell phones. And working out one identification with a field guide exposes them to many other exciting things they may find, and recognize, later.

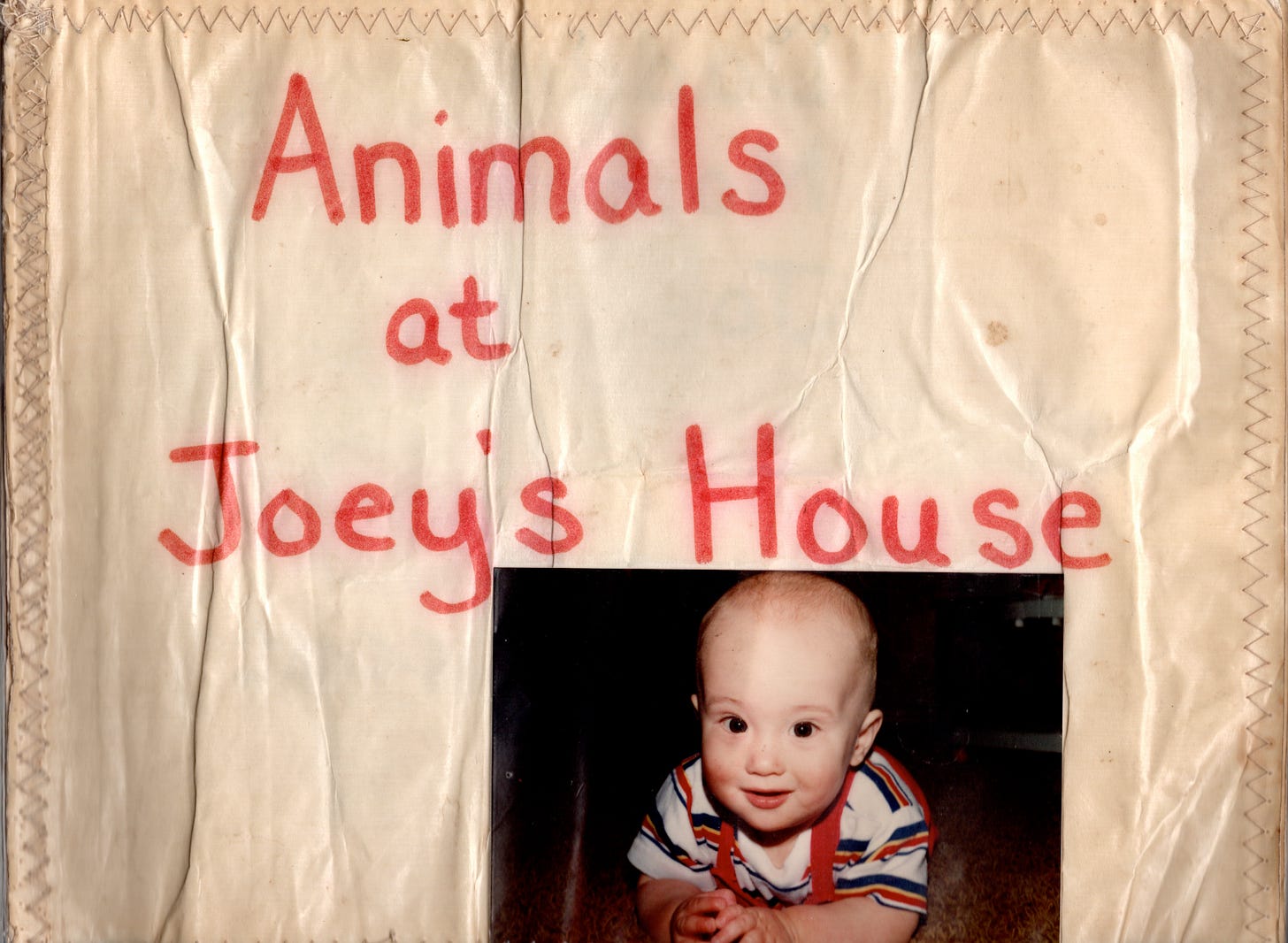

Personal family field guides are very fun to create. I made a homemade book, Animals at Joey’s House, for my first child, cutting out pictures from magazines for the illustrations.

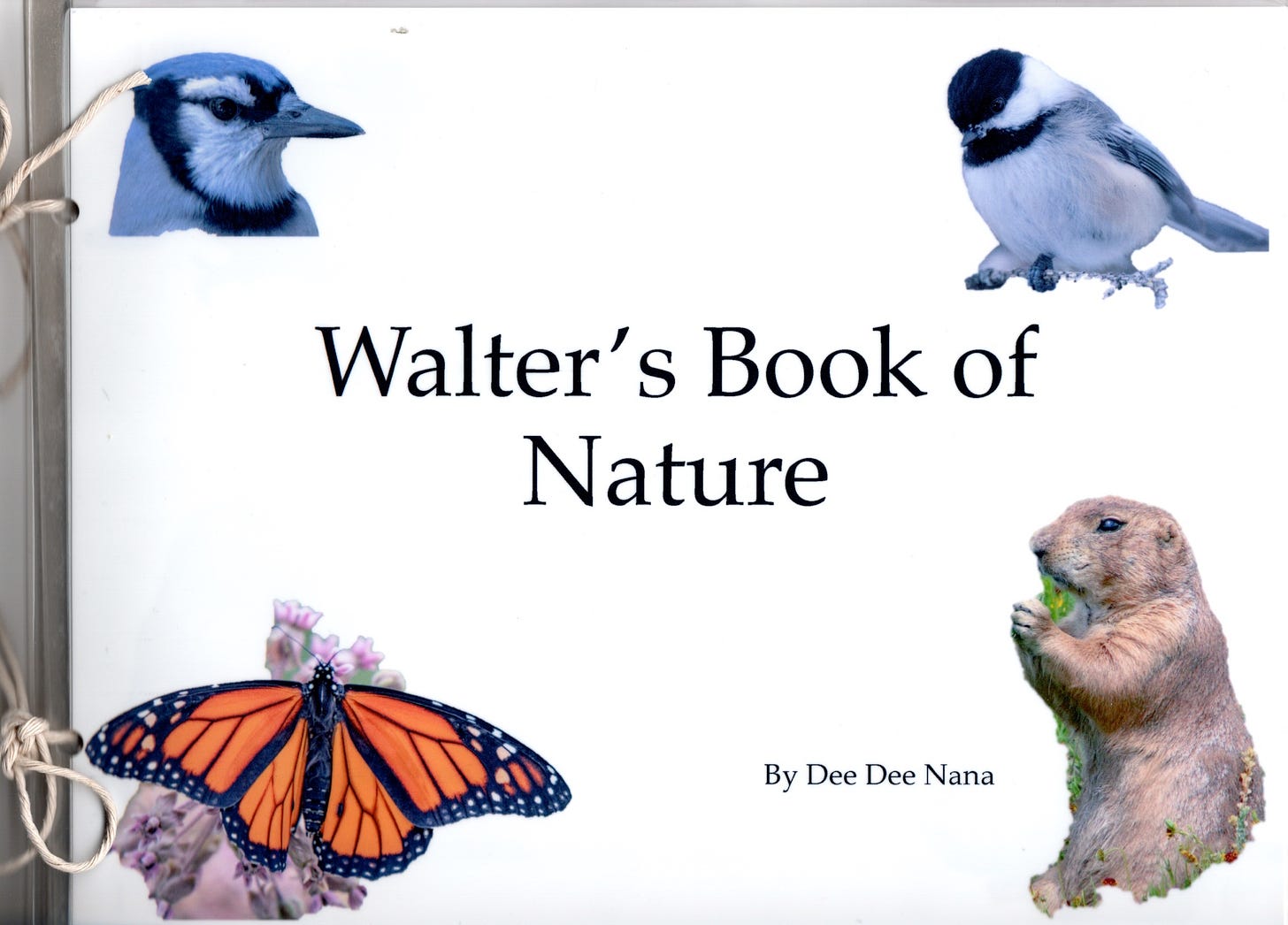

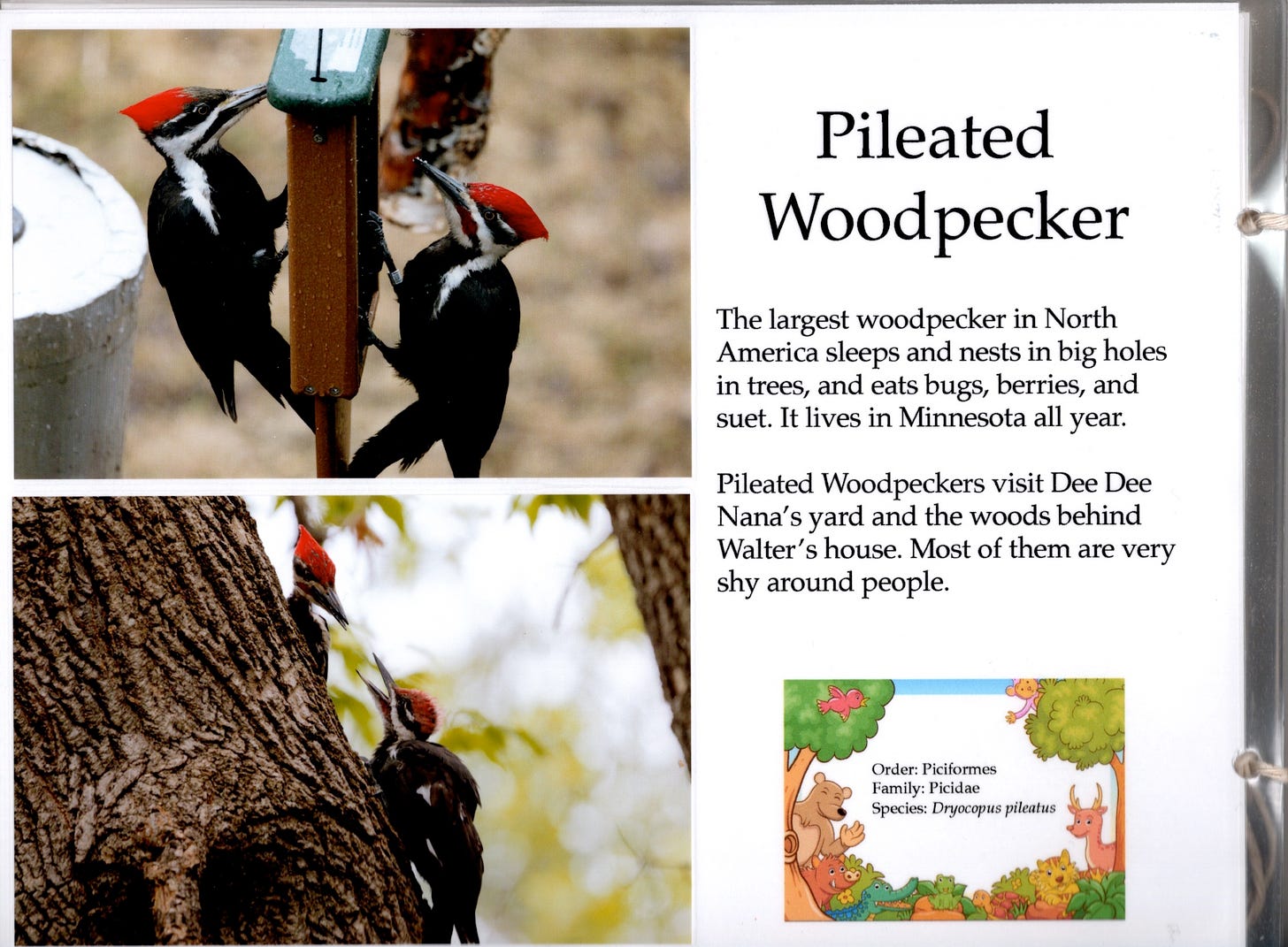

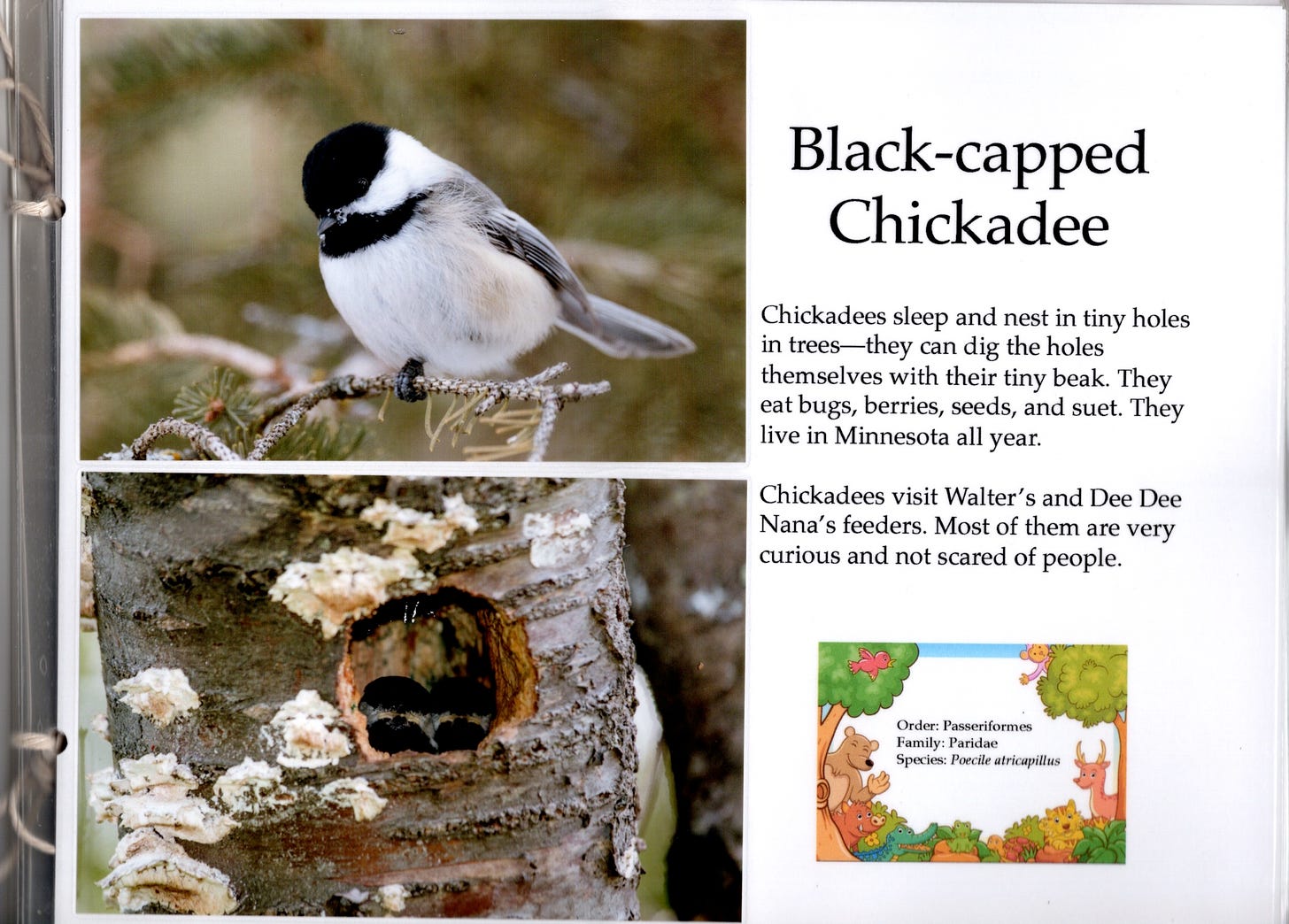

Now that I’ve amassed a huge collection of photos, mostly of birds but also of common animals and a few plants, I’ve been creating Walter’s Book of Nature. Each laminated page has two or three photos of a species along with a little information, often mentioning how and where Walter saw it. Each page has two holes punched on the side, and I simply tied them together, though binder rings would work just as well, so I can continue to add more species over time.

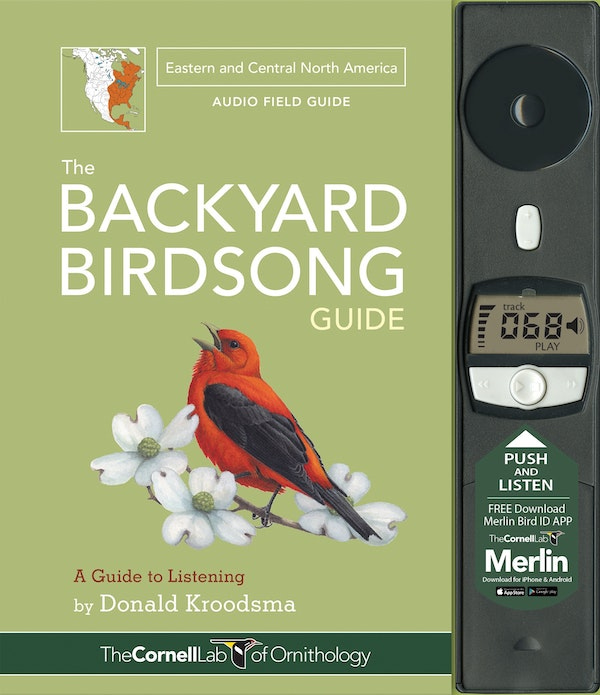

Just about all of us use our ears as well as our eyes to identify at least some birds. Several books out there have buttons to press that play songs, such as the excellent Backyard Birdsong Guide by Donald Kroodsma and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Make sure to listen to these books, especially lower-cost ones, before purchasing, because the tiny, cheap speakers in some of them distort the lowest and highest frequencies such that the birds won’t sound very good.

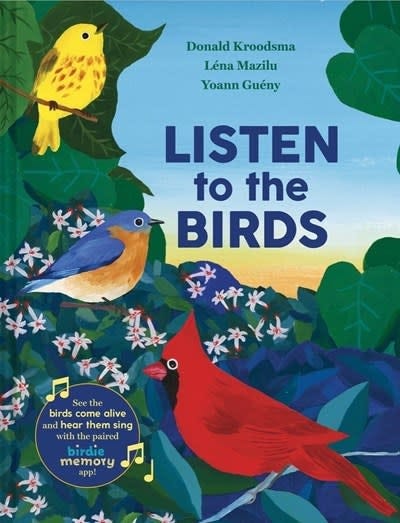

Donald Kroodsma just wrote a brand new bird song guide, Listen to the Birds, that covers 20 Eastern and 20 Western species of North America.

This book has a new and exciting gimmick that captivates Walter. It does require the use of a smart phone or tablet, which first reads a QR code so you can download and install the free “birdie memory app.” Then when you point your phone’s camera at any of the book’s vivid and appealing images, the screen makes the bird come alive—not only do you hear the sound, but the picture is suddenly animated so you can see the bird opening its mouth and changing its posture as it sings. I don’t know how to capture a video of this, but it’s really cool, and Walter loves when we read that book together. The text provides, simply but accurately, a lot of fun and fascinating information about each species that will help adults explain what the bird songs mean.

The best field guides—published or do-it-yourself, with or without bird sounds—are still little more than word books to help us expand our toddlers’ vocabularies and understanding of the world around them. Most children prefer stories with characters and plots at bedtime. So next time I’ll focus on a few bird books that tell a story that at least one toddler I know enjoys.

I love this so much. I was one of those little children that poured over books on birds and nature...when they were available. Childrens lives are so enriched with learning about the miracles of birds and habitats.

You win the best Mom and Grandma award!!