An Auspicious Start to "The Year of the Chickadee"

2025 marks an important anniversary for me.

(Listen to the radio version: Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.)

On March 2, 2000, I celebrated the 25th anniversary of my becoming a birder and noticed that the 50th anniversary would be on March 2, 2025. Ever since, I’ve considered that date something to look forward to. Indeed, it was 25 years ago that I started musing about how I might celebrate this entire year, informally calling it my “Project 2025.”

Last year, when I started hearing about an entirely different, much more ominous Project 2025 and realized we’d be facing dark days ahead, it took some of the luster from my own Project 2025, but as much as I intend to resist the billionaire takeover of our democracy, I’m not going to let them steal my enjoyment of this long-anticipated year. That memorable morning of March 2, 1975, set the course for my entire life, and I intend to enjoy this year.

As I always do on New Year’s Day, I eagerly anticipated what my first bird of 2025 would be. I stood at my office window starting at 7:30, while it was still dark, and at 7:55, there it was—a chickadee, the very first bird I’d seen when I started birding, too. What an auspicious start to the year!

Fifty years ago, I didn’t realize such an adorable and common bird—the state bird of Massachusetts—even existed. Chickadees weren’t mentioned in the “bird” entry of my childhood encyclopedia set and weren’t among the 18 species depicted in the Golden Bird Stamps book my Grandpa gave me. I had no idea that when W.C. Fields called someone “my little chickadee” he was referring to a real bird.

I managed to graduate first in my high school class of 500 (yeah—Russ was #2) and with highest honors from Michigan State University without ever learning anything about birds, even though I loved them. Until my senior year in college, I was actually ignorant of the facts that I could take ornithology classes and that field guides existed. Most of the people I know who started birding as children had parents or a teacher who not just encouraged them but provided some of the starting tools. I think this is why I’ve always been patient and understanding when people ask me what some other birders consider stupid questions.

Some of my very first memories involved the House Sparrows cheeping outside our two-flat apartment in Chicago and pigeons flying up whenever a nearby drawbridge over the Chicago River went up, and I loved my Grandpa’s canaries. I fell in love with one television character—Pamela Livingstone (played by Nancy Kulp) on Love That Bob, who was a birdwatcher. Her birdwatching, geeky persona, and being an “old maid” supposedly made her ridiculous, but I loved her for, not despite, those qualities.

Pamela Livingstone had binoculars, making me forever after associate binoculars with birds, but my mother told me that television shows were fiction—in real life, only soldiers, spies, and peeping toms had binoculars. Sure enough, throughout my entire childhood, I never saw a real person with these magical tools. And I had no idea how Pamela Livingston knew what the names of all those birds were. When she mentioned a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker to loud guffaws on the laugh track, I wondered what on earth a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker was, and how had she learned about it in the first place?

As much as I loved birds, the only ones I recognized were pigeons, sparrows, robins, cardinals, and the shiny black birds with iridescent purplish heads and glittery eyes who often walked on our lawn in Northlake—my family called them crows.

When I was in first grade, we took a vacation at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, where I saw and heard a real live Blue Jay—one of the birds on the cover of my bird stamp book. I can still picture it, even more beautiful in life than in the book, up in that leafy tree.

And one morning a rainbow of tiny, brilliantly colored birds materialized in the maple tree right outside my bedroom window. My mother said someone’s canaries must have escaped, but these were too bright compared to my Grandpa’s canaries. He’d told me about the canaries who had died saving miner’s lives, and I concluded that these must be the angels of those brave little heroes.

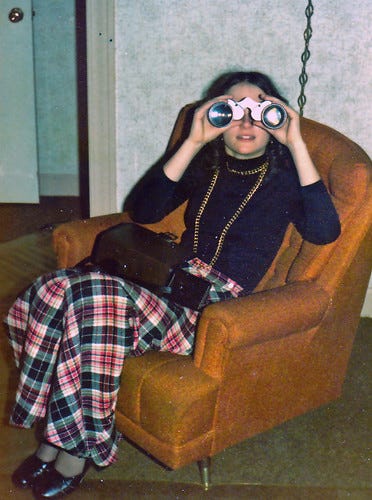

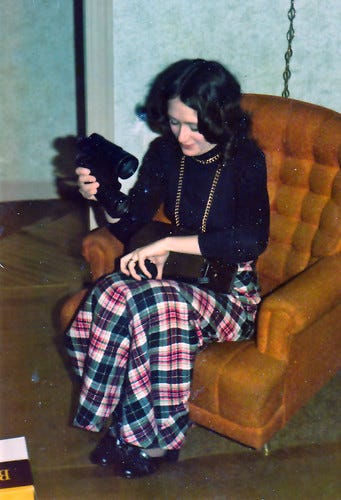

On Christmas 1974, when I was 23, I opened my presents from Russ’s parents to behold a bird field guide and binoculars. A Christmas miracle!

I could hardly head out birdwatching willy-nilly. After so many years of yearning, birdwatching felt sacred to me—such an important, precise activity that I tucked the binoculars back in the box. I’d keep them there until I knew what I was doing.

I read that Peterson guide cover to cover, then paid $3.95 plus tax for the Golden guide (Russ and I were living on $300 a month, so of course I entered this expense in our budget book) and read it cover to cover, too.

I very much liked the little lines Peterson used to point to each bird’s salient field marks, but in every other way, I preferred the Golden guide. Its illustrations faced the detailed information about each bird (with range maps), while the illustrations in the Peterson guide (second revised and enlarged edition) were scattered throughout the book, completely separated from most of the information about the birds, and there were no range maps. I also preferred Arthur Singer’s drawings to Peterson’s, whose disembodied, “cookie cutter” birds faced the same direction in the exact same poses on blank pastel backgrounds.

Singer’s depictions of birds in lifelike poses, each in a bit of natural vegetation, was not only more attractive; it gave me a sense of how different groups of birds move and perch, and suggested a bit about a likely habitat for each species.

To get the best of both books, I painstakingly drew Peterson’s brilliantly conceived lines pointing to field marks into my Golden guide. It was a great exercise in getting more familiar with the birds I might see.

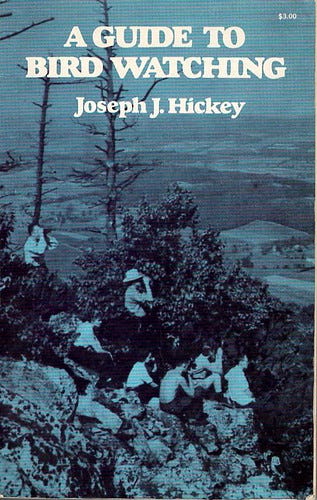

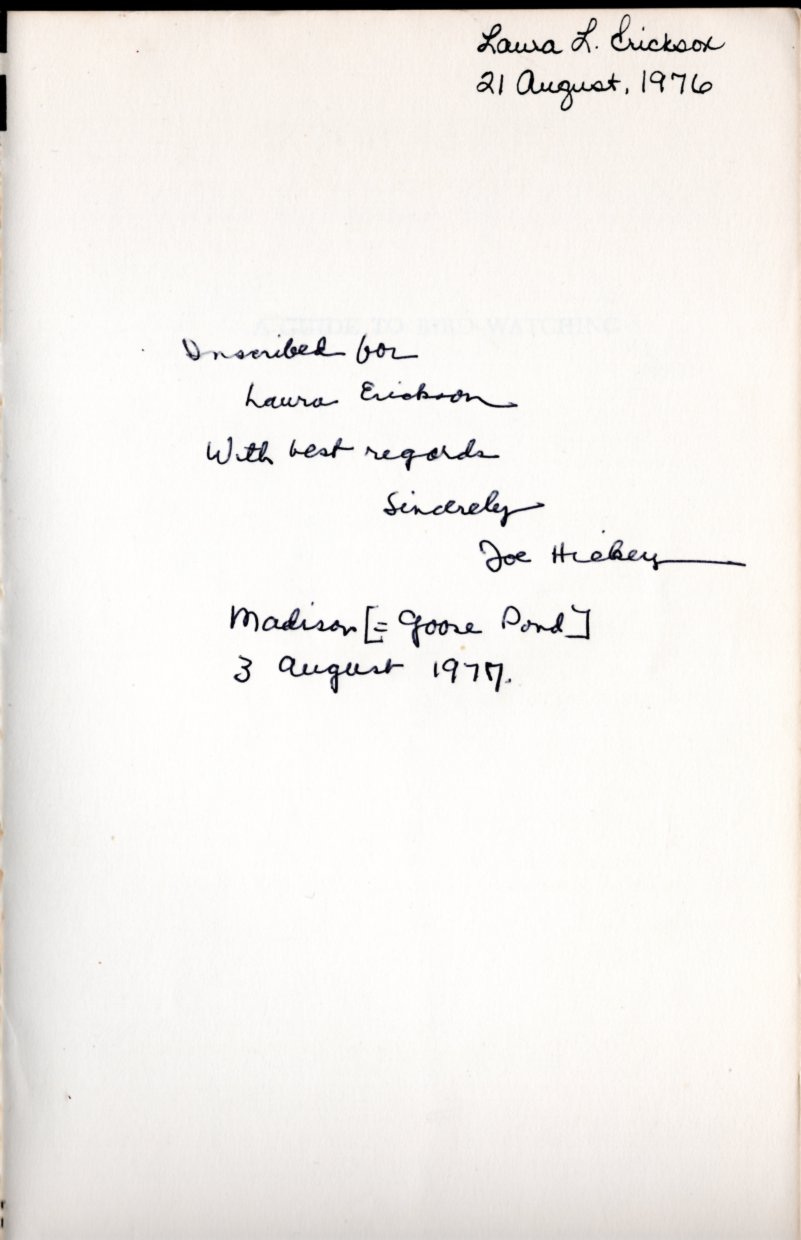

I still didn’t feel ready, but I found an extremely helpful book in the MSU library, A Guide to Birdwatching by Joseph Hickey, and read that cover to cover.

Hickey was so encouraging! As a boy without binoculars, he’d climb high up in trees to get closer to warblers. When he received a pair of 2x opera classes, he wrote that it was a turning point in his life. “After all, 2-power just about doubles one’s potentialities.” And my binoculars were 7-power!

Finally, on March 2, 1975, a full 67 days after putting them back in the box, I took out my “virgin” binoculars (I called them that because they’d never once focused on a bird) and my Golden guide, already marked up with little lines pointing to the most important field marks on every Eastern bird, and drove to Baker Woodlot. I felt ready, eager, and very excited!

I quietly walked the short way from the entrance to the huge boulder where the path split. There was still snow on the ground, but I nodded my head in acknowledgement of two tiny graves hidden behind the rock, where my beloved gerbils were secretly buried, whispered to their spirits “Wish me luck,” and took the path Russ and I frequently strolled along. Familiar as I was with Baker Woodlot, I’d never noticed a bird there before, but I had faith that my binoculars and field guide, like a pair of mythical, avian-focused divining rods, would magically lead me to one.

And they did! I don’t know how long I walked before suddenly, there it was—the first bird I ever looked at with binoculars, and the first bird my Bushnell 7x50 Instafocuses ever beheld.

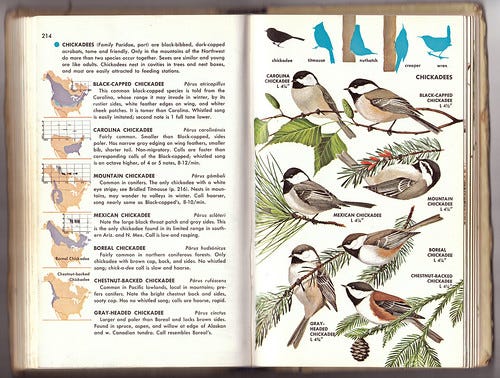

I raced through the field guide hoping I’d find the page showing this tiny thing before it flitted off. When I came to the chickadee page, I held the place with my left thumb as I kept paging through just in case there were other black-capped birds with white cheeks and a black bib elsewhere in the guide. The Blackpoll Warbler’s head looked almost right, at least in profile, but the back and sides were completely different.

I kept on just in case there was another one, but there wasn’t. (A few years later, I mistook a Golden-winged Warbler for a chickadee. He was directly above me, mostly hidden by leaves in a high branch, and for a quick moment from that precise angle, the black bib and cheeks looked exactly like a chickadee’s, but then I got a glimpse of yellow. No way did the Golden-winged Warbler in my field guide look anything like a chickadee!)

It had already taken several minutes to confirm that this was a chickadee, but miraculously, the little bird stuck around, making endearing little dee dee dee calls and sometimes looking me straight in the eye. In retrospect, I would bet that I was seeing a flock of several, but at the time I had no clue about their social habits. I just kept looking back and forth between the bird and the field guide, trying to figure out which chickadee it was.

The range maps didn’t show state lines and I wasn’t all that geographically literate, so I couldn’t tell if this was a Black-capped or Carolina Chickadee by range. The guide said the Black-capped had “rustier sides” and “whiter cheeks,” but wouldn’t you need to see both to judge? It also mentioned white feather edges on the Black-capped Chickadee’s wings, which I was pretty sure I was seeing, but I’d have felt better about that, too, if I could see the two species side by side.

According to the field guide, the whistled songs were quite different, but this one wasn’t whistling. The calls I was hearing were supposed to be faster in the Carolina than the Black-capped, and this, finally, was a comparison I could make, not right that moment but at the university library, where I had learned there would be bird recordings. As I studied the bird, I grew more and more certain that it was a Black-capped—the wing feathers really did seem to have white edging, and the field guide mentioned that the Black-capped was tamer, which certainly described this cooperative little bird. Yep—my new binoculars and field guide were magical!

I stood firm the entire time the chickadee(s) stayed in view and then ran back to my car and hightailed it to the library where I pulled out the Peterson record album, sat down in a cubicle, popped on headphones, and listened to the chickadees. And voila! The number one bird on my life list was definitely a Black-capped Chickadee.

This wasn’t just an identification and the first entry on my life list. The confiding little chickadee I’d spent so many minutes with was tinier than the sparrows I shared McDonalds French fries with and, unlike those sparrows, who approached only for food, this one seemed genuinely interested in me, its black eyes sparkling with intelligence, vivacity, and what sure felt like friendliness. And it posed in so many different ways, vocalizing almost constantly, that I was as grateful for its help as I was overpowered with joy. That chickadee transformed me into a real live birdwatcher and taught me from the start that birds are far more than a set of field marks to figure out. Even though in those first years I was hellbent on finding every bird I could, I hadn’t had my fill of chickadees yet. Fifty years later, I still haven’t.

So it feels imperative to honor that first inspiring chickadee this coming March 2 by looking for another one—maybe one of the original’s descendants—at Baker Woodlot. Russ and I already have our hotel reservations.

Throughout my official Year of the Chickadee, I want to enjoy some of the other wonderful birds that that first chickadee made possible. I saw my first warblers—Black-and-white, Nashville, Magnolia, and Black-throated Green—on May 11, 1975, and my first Blackburnian Warbler on May 13, so Russ and I plan to be in Ohio at the birding festival called The Biggest Week in American Birding for those anniversaries. The Biggest Week is held at the Black Swamp Bird Observatory, the most reliable place I know to get closeup looks at an abundance of almost every Eastern warbler and more!

This month I’ll head to the Sax-Zim Bog to see Minnesota’s other chickadee—the Boreal—along with an assortment other cool winter birds. Then on Valentine’s Day I’m headed somewhere warmer—Cuba. I’ll see myriad Caribbean birds including several endemics—species found nowhere on the planet except Cuba—like my “target species,” the Cuban Tody.

This eye-popping delight is almost exactly the same size as a chickadee, and I’m in love with it. I was so obsessed with seeing a Cuban Tody that for several years back in the early oughts, if you did a web search on “most adorable bird in the universe,” Google listed my blog post about the Cuban Tody at or near the top of the search results. Russ sent me there in 2016, and 2025 seems like the right year to return.

Russ isn’t coming along on this trip, but he will come along later in the year when we go to Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic to see the world’s other four tody species, none of which I’ve seen before. I’m calling this my “Tody Sweep.” I’m also signed up for a Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 3-day boat trip to the Dry Tortugas in April.

I’m trying to pace myself now that I’m in my dotage, and these plans will keep me a little busier than I liked even when I was younger—I’ve always been a moseyer. But my Project 2025 will allow me to be the master of my fate and the captain of my soul even as anti-environmental, anti-conservation forces work to eviscerate the laws and regulations that protect our air, water, land, and wildlife. As Edward Abbey1 wrote:

Be as I am — a reluctant enthusiast... a part-time crusader, a half-hearted fanatic. Save the other half of yourselves and your lives for pleasure and adventure. It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it’s still here. So get out there and hunt and fish and mess around with your friends, ramble out yonder and explore the forests, climb the mountains, bag the peaks, run the rivers, breathe deep of that yet sweet and lucid air, sit quietly for a while and contemplate the precious stillness, the lovely, mysterious, and awesome space. Enjoy yourselves, keep your brain in your head and your head firmly attached to the body, the body active and alive, and I promise you this much; I promise you this one sweet victory over our enemies, over those desk-bound men and women with their hearts in a safe deposit box, and their eyes hypnotized by desk calculators. I promise you this; You will outlive the bastards.

From a speech to environmentalists in Missoula, Montana, and in Colorado, which was published in High Country News, (24 September 1976), under the title "Joy, Shipmates, Joy!", as quoted in Saving Nature's Legacy : Protecting and Restoring Biodiversity (1994) by Reed F. Noss, Allen Y. Cooperrider, and Rodger Schlickeisen.

Wonderful article. I love the concluding quote!

Wishing you a great year and may your dream birds show up for you!

Thank you for your inspiration!

Susan K.

This is such a wonderful story. The way you prepared for your first chickadee sighting, and the way you described it afterwards, both carry the hallmarks of a sacred experience -- which it was.