Birding with a Camera

You don't need to be a photographer to have fun taking pictures.

(Listen to the radio version here.)

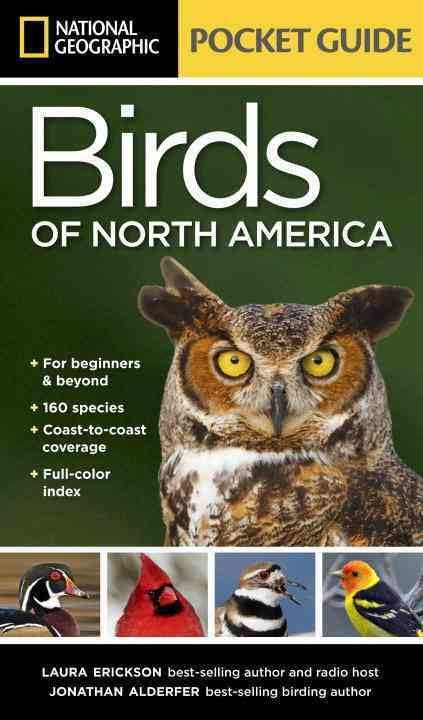

When I was writing the National Geographic Pocket Guide: Birds of North America, my co-author Jonathan Alderfer (who was co-author/photo editor/project manager for just about all the National Geographic books about birds for decades) told me he wanted to use one of my photos in the book so I could legitimately call myself a “National Geographic photographer.”

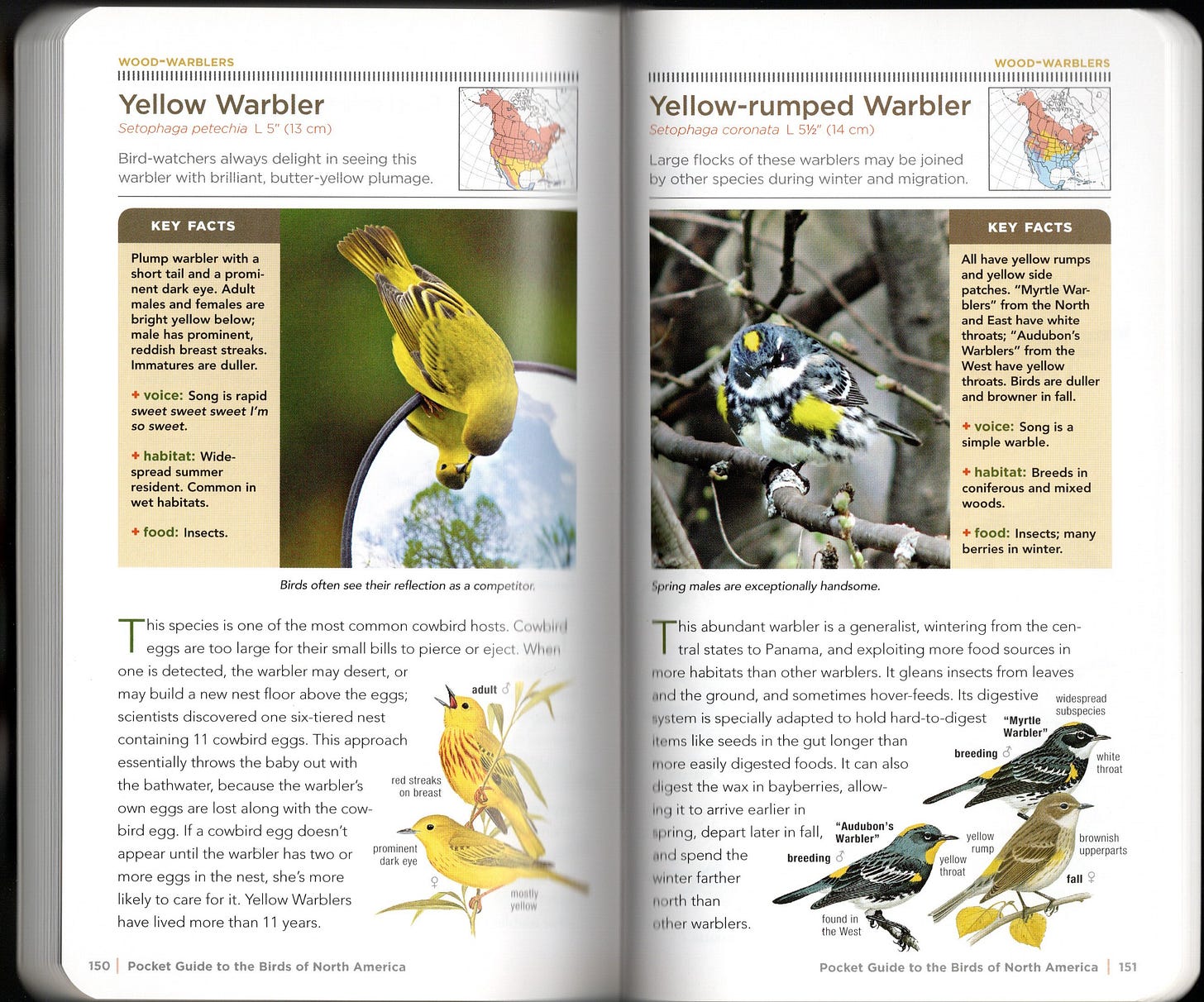

That seemed hilarious because I don’t consider myself a photographer—I’m a birder with a camera. The photo I chose was taken with a point-and-shoot camera (a Canon PowerShot S2 IS) on May 3, 2006, while I was leading a warbler walk at Park Point. A couple dozen people showed up, surprising since the temperature started in the teens and barely climbed to 20º. I was shivering when we came upon a cold little Yellow-rumped Warbler, all fluffed out with an expression like a Jane Austen character saying “I am most seriously displeased.”

Taking the photo—really, just a snapshot—was hardly an achievement—it’s simply a souvenir of a lovely experience. But I confess that once I did mention something about National Geographic publishing one of my photos. I was birding alone when a guy lugging two Nikons with long lenses saw my long lens and started showing off photos on his cameras and listing awards he’d won. When he handed me a business card and patronizingly invited me to contact him if I ever needed advice, well… wouldn’t you have dropped the name “National Geographic” at that point?

For 25 years, I birded the traditional way, with binoculars and a spotting scope. But no one defined me by my tools—everyone understands that those optics simply help us get a better view. Now I’ve simply substituted a camera for the scope. (I’d named my scope Sacajawea.1 She recently retired to Cuba where I hope she’s enjoying lots of lovely birds.)

My current camera has a 500-mm lens, comparable to 10x binoculars, so it provides nowhere near the magnification my spotting scope did. But the camera’s 48-megapixel sensor allows me to zoom in on images when I get home to see details I could never have seen in the field. Even at close range, I can’t take in, much less savor, every detail of a bird in the moment the way I can when I study my photos.

My being in the habit of photographing so many of the birds I come across came in handy just today. I took a walk at Waabizheshikana, or what we used to call the Western Waterfront Trail. I got to see plenty of early migrants—two pairs of Trumpeter Swans; Canada Geese getting into territorial squabbles; a couple of skulking Hermit Thrushes; Song Sparrows, American Robins, and Red-winged Blackbirds calling from just about everywhere. Several species of ducks were swimming about and I was hoping to get some closeups, but they disapprove of paparazzi and kept their distance.

Then I picked out a distant Common Merganser just as he came up from a dive, and he seemed to have something in his beak. I instantly pulled up my camera and started shooting away on burst mode. I ended up with 42 fairly in-focus shots of the bird trying to down a ginormous fish that my good friend Mick Fiocchi identified as a northern pike.

With my binoculars I could see the fish thrashing and the duck struggling to swallow it, but I never could have picked out the details that my photos show, even with my spotting scope. I thought the duck might win the battle, but the fish was just too big. Finally the merganser spit it out and swam nonchalantly toward a female. I don’t know if she was impressed or not; before I could get her photo, she dived. The pike went under and is probably right this moment salivating over the thought of dining on baby mergansers in a month or so.

I have no idea how far I was from this exciting interaction. I’m terrible at gauging distances, usually leaving that to my camera, which provides a pretty accurate focus distance in the photo’s EXIF information. This time it said the distance was infinity, the exact same as when I photograph the moon, though I’m pretty sure the duck and fish were closer than that.

As Forest Gump almost said, birdwatching, whether you’re using binoculars, a spotting scope, or just your own senses, is like a box of chocolates—you never know what you’re going to get, but it’s certain to be sweet. Birding with a camera is just as sweet, and leaves you with a lovely, lingering aftertaste as well.

I named my scope Sacajawea because she showed me so many spectacular things that I took all the credit for.

Congrats on your new birding guide!

And I also love the way you put the mansplaining guy in his place!

Xxx Susan

Helmeted Guineafowl...wow! With those long eyelashes, it could be a "she"?! Your stories are as special as your pics!