Birds and Transmission Lines

Clean energy should be making us less, not more, reliant on huge transmission lines.

(Listen to the radio version of the first part of this post here, and the second part here.)

In 1970, when America celebrated the first Earth Day, I was a college freshman who thought the word “chickadee” was nothing more than a funny W.C. Fields term of endearment, and I truly had no clue about environmental issues. I didn’t understand much more after Earth Day, but I did come away with an absolute commitment to energy conservation.

Two of the longest, most detailed entries in my 2006 book, 101 Ways to Help Birds, are #14: Conserve electricity, and #30: If your property provides space for power lines, communications towers, or wind turbines, make sure they are bird safe. I didn’t delve nearly enough into solar power, which wasn’t in wide use except for heating water 20 years ago, but in both entries I did get into the issue of energy transmission and how no matter how clean the energy source, transmitting it long distances along power lines involves serious risks to humans as well as birds. I should have included information about how even though underground transmission lines are more expensive to build, in many cases they’re better in the long run, preventing bird collisions and power outages due to vandals, acts of terrorism, and weather events exacerbated by climate change, such as more frequent and powerful tornadoes, hurricanes, blizzards, ice storms, floods, and fires.

I learned firsthand about the hazards of transmission lines at National Audubon’s Rowe Sanctuary along the Platte River in Nebraska, where hundreds of thousands of Sandhill Cranes gather every February and March to rest and fuel up in preparation for their final leg of migration. My visit to the sanctuary in March 1996 coincided with an exceptionally cold period—so frigid that cranes were bending their legs to hold their feet against their bellies in flight. When I got home, I wrote a “For the Birds” segment about it:

Most of the Platte was frozen, and the flowing open water carried big chunks of ice, which would pummel and abrade any crane legs that stood in it. So at day’s end, the birds had a terrible time finding safe places to sleep for the night. Although they normally settle in on the river around sunset, during this awful period many of them were still flying back and forth over the river searching for a safe bed of water well after dark. And in the darkness, many of them smacked into the power lines strung across the river.

There are two sets of wires at the Rowe Sanctuary where tens of thousands of cranes sleep. These wires have been regular death traps for the cranes, and in these conditions, these poor cranes didn’t have a chance. [The very morning of my visit,] seventeen dead ones were found under one set of wires. The leg of one and the wing of another had been ripped off by the impact. One crippled crane huddled on the ice. It would eventually freeze or starve unless an eagle or coyote got it first. …

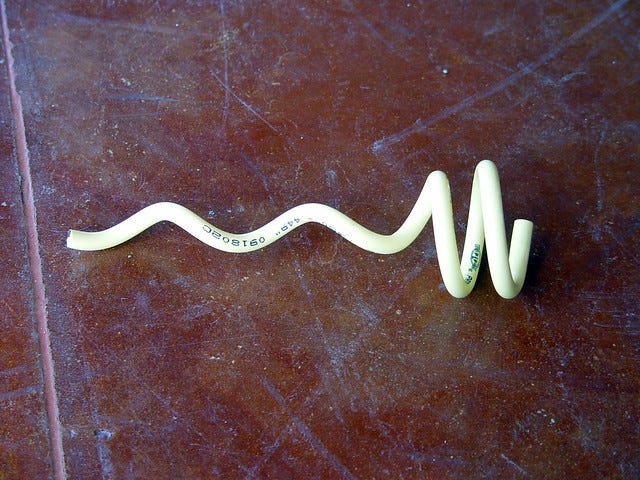

Another set of wires had been fitted with plastic spirals [“bird diverters”] designed to be visible to birds. Only one dead bird was found beneath those. The Audubon sanctuary paid a third of the cost to put those spirals on, and the pattern of this season’s deaths prove that they work. …[But] for now, cranes will continue to bonk into wires over the Platte River, an awfully high price to pay for electricity.

Birds colliding with transmission wires pose dangers to humans as well. In 2001, a Trumpeter Swan was electrocuted at a transmission line at a popular birding spot in my neck of the woods, in Saginaw, Minnesota. Power was knocked out and the poor bird’s smoldering body ignited a wildfire. In 2004, a major fire in the foothills of Santa Clarita, twenty-two miles southwest of Los Angeles, charred over 5,000 acres and caused the evacuation of 1,600 homes; that fire was ignited by the burning body of a Red-tailed Hawk electrocuted by a power line. At the time I wrote my book, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was estimating that more than 1,000 hawks and eagles were being electrocuted at power lines every year. In 2022, Joshua Rapp Learn of the Wildlife Society posted a recent study about fires caused by raptors being electrocuted.

There’s been quite a bit of research on various kinds of flight diverters, from the simple little spirals they were retrofitting the wires with at the Rowe Sanctuary in 1996…

… to more complicated ones that have movement and are even illuminated. They’re all quite cheap and studies have shown that they reduce collisions significantly, but retrofitting power lines is very expensive. In 1996, the $3,000 the Rowe Sanctuary would have had to pay to retrofit the rest of the lines on their property was prohibitive, and the power company had no desire or legal obligation to pay for it, even though it was responsible for those crane deaths.

In 2004, an Audubon spokesperson at the sanctuary told me that the long-term solution for places with so many vulnerable birds was for power companies to be required to bury transmission lines underground or, at the bare minimum, place flight diverters on every new transmission line during original construction or whenever old lines are replaced, especially in wetlands and places where large raptors frequent. (It’s birds with large enough wingspans to touch two wires at the same moment that get electrocuted and start fires.) Power companies should not wait until after disasters are documented and then expect non-profits to cover the costs of retrofitting the lines.

Tragically, without a legal mandate, there is no way even the richest corporations are going to opt for the more expensive upfront costs of burying lines, even if burying them would be so much safer for humans as well as birds, nor will they place those cheap little flight diverters on new and replacement lines unless required to. And these large power companies have a vested interest in keeping control over all power production, wanting to make sure their enormous profits continue no matter how much we replace fossil fuels with clean energy sources. They’d prefer to build enormous wind or solar farms hundreds of miles from the urban and suburban areas where the energy would be used rather than let property owners produce their own solar energy.

Because I saw those 18 mangled Sandhill Crane carcasses lined up in an outbuilding at the Rowe Sanctuary in 1996 (before I had a camera), I’ve always figured National Audubon understood the dangers of energy transmission lines, so I expected them to take the lead working toward mandates to construct more power lines underground or with flight diverters, and, even more importantly, to focus on energy conservation and fostering local production of clean energy. Back in the 1970s, regulations setting energy efficiency goals for major appliances and automobiles made a huge difference until corporations and politicians made “government regulation” a dirty word. And instead of expanding the enormous energy grids we’ve been increasingly dependent on in the fossil fuel era, we should be producing increasingly large amounts of clean energy right where it’s used, reducing our dependence on so many transmission lines in the first place.

This month at the AOS meeting, I attended a session about a 2023 report produced by Audubon titled Birds and Transmission: Building the Grid Birds Need. Based on the presentation, it appeared that Audubon was promoting the construction of more, not fewer, transmission lines throughout the country, but because the talk went over the time limit, there was no opportunity to ask questions. When I came home, I found the actual report online, and yep—Audubon is indeed supporting a much more massive electrical grid, carried via transmission lines.

Back when I was researching my 2006 book, Audubon was one of the many institutions still shying away from the “controversy” of climate change. Now that they have come on board, they’ve issued some wonderful reports about how vulnerable many species of birds are to various forces related to climate change. But in Birds and Transmission, Audubon focuses on how we need to massively expand the network of transmission lines crisscrossing the nation—up to 200,000 miles of new transmission lines!

The authors of the report seem to believe that building up our transmission line capacity will magically increase clean energy production, but transmission lines are indiscriminate, carrying electricity produced from dirty coal and other fossil fuels as well as wind and solar. One of the candidates in this year’s presidential election has been touting coal and oil and ridiculing clean energy—if he or anyone like him prevails now or in the future, Audubon’s recommendations would contribute to, not mitigate, climate change.

The report does discuss the importance of flight diverters to prevent collisions but doesn’t suggest installing them on new and replacement lines proactively, when they’d be most cost effective. Nope—even knowing how devastating a single bad night can be where vulnerable birds are concentrated, Audubon simply suggests adding diverters as a response after a power line is documented killing birds. This is unconscionable. Flight diverters should be an essential requirement for all new power lines, especially in wetlands and areas where raptors abound, where the collisions endanger both birds and humans.

Audubon doesn’t seem to understand how vulnerable to climate change transmission lines themselves are.

Even though Audubon is finally acknowledging the crisis birds are facing with the changing climate, they don’t seem to understand how vulnerable to climate change transmission lines themselves are. That AOS meeting was sandwiched between two hurricanes, Helene and Milton, that knocked out power for millions of people. Our solar and wind facilities, just like fossil fuel power plants, need to be constructed closer to, not further from, where the power is used to reduce our vulnerability to high-capacity transmission lines being damaged by vandals, terrorists, wildfires, floods, and other events that promise to grow even more dangerous in the future.

My house’s 12 solar panels produce more energy than we use on most summer days. This far north, our winter days are short and our heat is mostly generated via an electric heat pump, so our winter solar production is considerably smaller than our usage, but overall, way less energy, clean or dirty, is coming into to our house via transmission lines than before we had the panels installed. I’m seeing more and more families, businesses, and farms installing solar panels, and much, much more is possible. Virtually all cities of any size have a lot of acreage covered with flat-roofed buildings where solar energy could be produced, and I’ve been seeing more and more parking lots with solar canopies that provide wonderful shade for parked cars even as they generate energy.

This is hardly to say that we must get rid of transmission lines. But conservationists and major organizations promoting a healthy environment for humans and wildlife should be working with government, not corporations, to support programs that will help people produce our own clean power closer to where we use it, and help us use less energy to begin with. We should be getting away from our dependence on the very corporations that got us into this horrifying fix in the first place.

After being able to take a road trip to NE to see the Sand Hill Cranes a few years ago, I am more than sympathetic to getting the transmission lines underground, etc. It seems unconscionable that Audobon doesn't see the light...!

This and your work is so important. I'm trying to keep abreast of the wind farm project threatening GREATER PRAIRIE CHICKENS remaining in your state. Not sure I want to get you started on that. It's complex. You having to water down all your research and thoughts on that issue into a column seems impossible and a headache. I know you are at least doing what you can. A lot of VERY competent people at the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology and even the Southern Wisconsin Bird Alliance I know are on it. Our population growth and concomitant development need limits somehow. Your beautiful bird and birds deserve it.