(Listen to the radio version here.)

For many years, I followed the late Ron Pittaway’s annual “Finch Forecast.” Back in the 1970s, Pittaway first began making a connection between the summer cone crops of cedars, spruces, and pines in Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario and the winter numbers of siskins, crossbills, and grosbeaks there. As he worked out the connections between specific conifers and finches, he started to make predictions about winter finch numbers and shared his observations with friends and colleagues. When he started posting his Finch Forecast on an Ontario birding listserv in 1999, other listservs and birding networks started sharing the information. That’s how I learned about it.

I loved checking how his predictions matched the bird numbers in my yard—his accuracy was amazing. When he announced his retirement in 2020, two of his collaborators, Tyler Hoar and Matt Young, took over the Finch Forecast under the auspices of Matt Young’s newly-founded Finch Research Network (FiRN). This year’s eagerly anticipated Finch Forecast will be released on September 29, when you’ll be able to read it on the FiRN website.

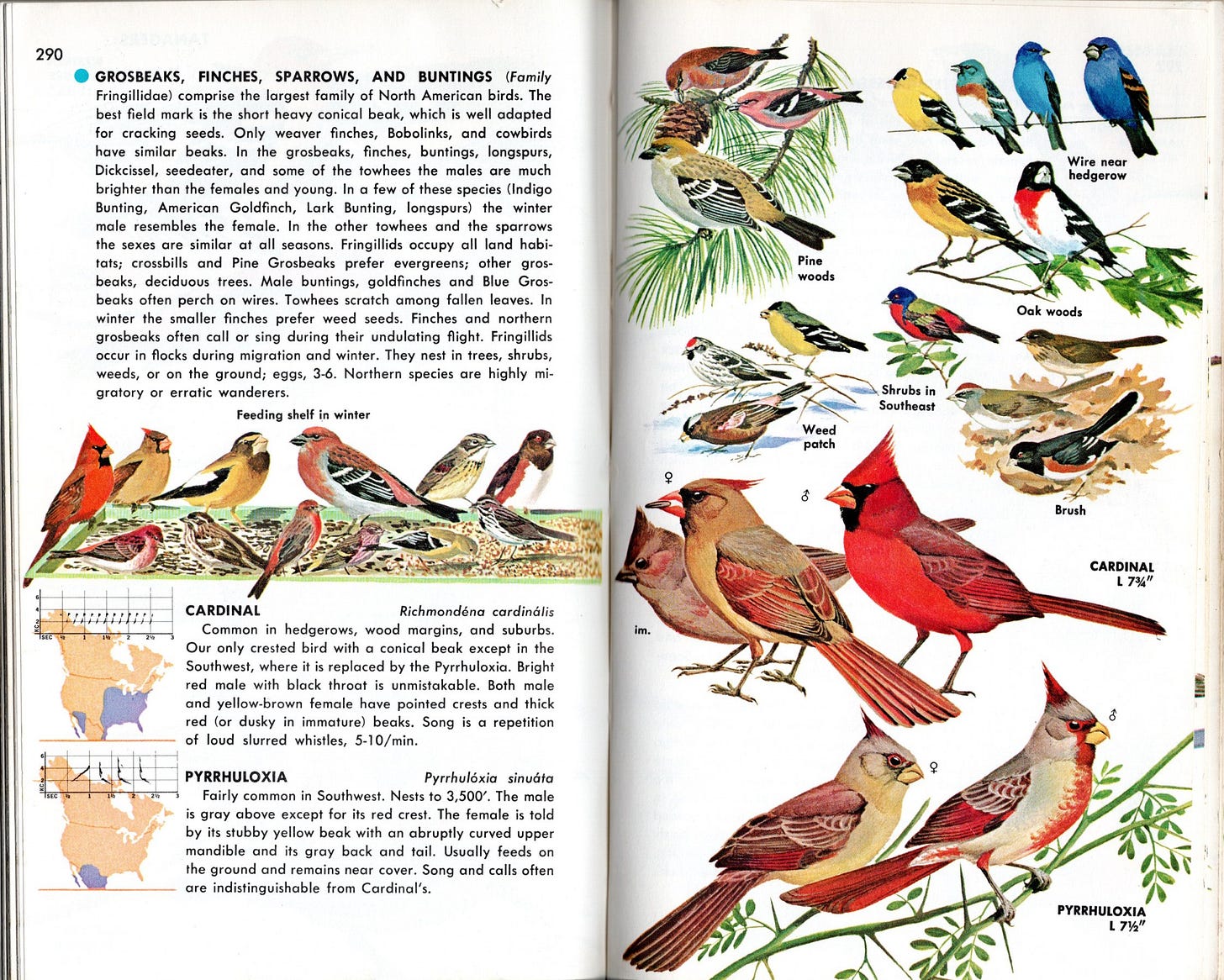

Meanwhile, long before I knew about the Finch Forecast, right after I started studying birds, the American Ornithologists’ Union’s Committee on Classification and Nomenclature changed the definition of what a finch even is. When I started birding, my then-current ornithology textbooks and field guides and the 1975 ABA Checklist, based on the AOU Checklist, defined the “finch” family, Fringillidae, to include sparrows, cardinals, grosbeaks, buntings, longspurs, and more—a total of 80 North American species not counting the Hawaiian honeycreepers. (At the time, the “ABA Area” didn’t include Hawaiʻi and the AOU Checklist didn’t include Hawaiian species.)

In July 1982, the AOU published a supplement to their Checklist with huge changes. Now they included the Hawaiian honeycreepers in Fringillidae, but suddenly the sparrows, cardinals, Blue, Rose-breasted, and Black-headed Grosbeaks (but not the Evening or Pine Grosbeaks), longspurs, and buntings had been reclassified into at least four different families. Now the “true finch” family, still called Fringillidae, was much smaller, including just 23 North American species plus the Hawaiian honeycreepers.

The names of true finches can be confusing. The family does not include the Saffron Finch of South America (introduced to Hawaiʻi), nor the bullfinches, seed-finches, or a handful of other birds with “finch” in their names. I’d had to memorize all the order and family names when I took ornithology classes in 1975 and 1976, so I had a lot to relearn, but the truth is, no matter when we first learned bird names and families, at least some of what we knew as fact quickly became obsolete.

Just this year, I lost a bird on my life list when America’s Common and Hoary Redpolls and Eurasia’s Lesser Redpoll were all lumped into the same species, now simply the Redpoll. The whole point of science is to ask questions and develop and improve tools and methods for finding the best answers. The more we learn, the better our questions, leading to new and better answers as well as changes to our life lists.

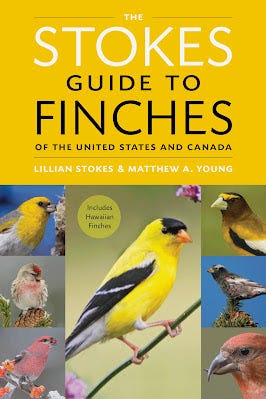

Now, on September 17, 2024, the newest in a very long line of Stokes bird guides is being released. The Stokes Guide to Finches was written by Lillian Stokes and Matthew Young. Lillian Stokes’s name, of course, is on 35 previous Stokes guides, and Matthew Young is deservedly known as the Finch Guy. (When I recorded an interesting Evening Grosbeak vocalization I’d never read about, I emailed Matt who checked all the recordings at the Macaulay Library to see if one was on record. Nope! He’s also an authority on crossbills.)

As with other Stokes guides, The Stokes Guide to Finches is written for new as well as experienced birders, the information presented in a straightforward, accessible, and fun way. And it’s a gorgeous book, providing more than 345 beautiful photos of the 43 species covered. It of course includes identification info along with a lengthier section on distribution than we see in most field guides, because so many finches are “irruptive”—the very reason that Finch Forecast is so valuable each year.

But The Stokes Guide to Finches goes way beyond what we’d find in a field guide. Every one of our regular mainland American species is given an entry that includes a lot of valuable information about behavior, feeding habits (including at our feeders), vocalizations, and conservation, plus interesting anecdotes and stories. All but one of the species entries for the 18 regularly-occurring mainland species vary from 8 pages to 16. The exception is the Red Crossbill, which has 34 pages!

Each of these regularly occurring mainland species entries has a “Quick Take,” usually two–four pages long giving some interesting information about the species. These vary stylistically. I’d have preferred the information in the Lawrence’s Goldfinch “Quick Take” to be written in a straightforward manner rather than as a fictional “interview” with one, but Lillian Stokes has always had a much larger readership than mine and she knows what her readers like and expect. However it was presented, it included interesting information.

Hawaiian honeycreepers are each given the same 2-page coverage as the vagrant Eurasian finches that occasionally appear in the United States and Canada. Including those honeycreepers at all was valuable because, as the authors note, Hawaiʻi, where over 50 species of endemic honeycreepers once lived, is down to just 16, some still critically endangered and even on the edge of extinction. As Americans, we are responsible for the wellbeing of our nation’s wildlife.

Not much is mentioned about the factors involved in the declines of so many Hawaiian birds within the species entries. Because the Palila is one of my favorite species, I do wish they’d mentioned as a “fun fact” that this is one of the only birds ever named by species in the title of a lawsuit: (1978’s Palila v. Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources) because feral game animals, especially sheep, were devastating the māmane-naio forests the Palila depend on. The bird won the court battle but is losing the war thanks to continued overgrazing on public and private lands and a devastating, long-lasting drought. The heat and lack of rainfall have prevented the remaining māmane from producing fruit (which Palilas need to produce eggs), and caused many re-planting programs on fenced-off lands to fail.

Many endemic Hawaiian birds have been devastated by diseases, especially avian pox and avian malaria, both transmitted by mosquitoes. Climate change is exacerbating this problem, too, as rising temperatures allow the mosquitoes to reach higher and higher elevations, dramatically shrinking safe habitat. The Hawaiian Honeycreeper section in the “Research and Conservation” chapter of The Stokes Guide to Finches covers in some depth the current strategy for trying to reduce mosquito numbers.

But no mention was made of “rapid ʻōhiʻa death”—a horrible fungal disease that is rapidly taking out the ʻōhiʻa lehua trees that many of the honeycreepers, including my own beloved ʻIʻiwis, depend on for nectar.

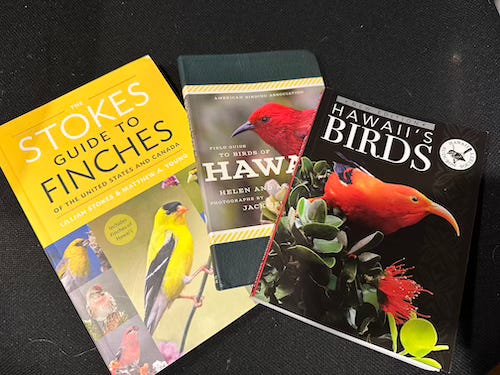

After my trip to Hawaiʻi this year, I came home committed to bear witness for these splendid birds and the critical issues they are facing. I could wish The Stokes Guide to Finches included more of that kind of information, but we only save what we love, and people have to be introduced to these birds before they can even start to love them; The Stokes Guide to Finches makes a lovely introduction to Hawaiian honeycreepers that might even inspire some readers to visit the state. It’s not a book you’d bring on the trip—the Hawaiʻi Audubon Society’s Hawaiʻi’s Birds, which includes all the species found on the islands, not just the honeycreepers, is much smaller and at 8.2 ounces, weighs just a third of what the 332-page Stokes guide does.1

My personal favorite part of The Stokes Guide to Finches is the in-depth discussion of crossbills—the reason the Red Crossbill entry is 34 pages long. In 1993, a scientist named Jeffrey Groth did a landmark study, publishing a short communication in The Auk and a monograph for the University of California Publications about 8 different Red Crossbill “call types” after discovering evolutionary differentiation in body size, bill shape, and vocalizations in these nomadic birds. Suddenly birders spending a lot of time with crossbills started recording them to work out what “call types” they were finding. Within a few years, four more “call types” were identified.

One of those call types belongs to a much less nomadic population found almost exclusively in Cassia County, Idaho, on two lodgepole pine “sky islands” separated from the Rocky Mountains enough that red squirrels, a major competitor for pine seeds, are not found there. The measurable differences in vocalizations, bill shape and size, and DNA from other Red Crossbills led scientists to split that form, the Cassia Crossbill, into its own species. The remaining 11 call types remain within the Red Crossbill complex.

Ever since my hearing went down the drain, I can’t pick up the call type differences on my own, but it’s fun to watch other birders recording and keeping track of Red Crossbill calls. The Stokes Guide to Finches manages to make all this not just understandable but fun and interesting, providing a lovely challenge for birders who can find, and still hear, these splendid birds.

The Hoary and Common Redpolls were lumped after The Stokes Guide to Finches went to the printer. Fortunately, the authors knew the question was up for a vote that might pass, and they managed to gracefully cover both forms of what they term the “redpoll complex” in a clear and helpful way. Species or not, it’ll always be fun to look for the frosty Hoaries within redpoll flocks.

The publishers sent me a free copy. I don’t buy many books anymore, but I’d have been happy to pay for The Stokes Guide to Finches.

I weighed this and my two Hawaiʻi guides on my kitchen scale:

• Stokes Guide to Finches, 1st edition 2024 (Stokes and Young): 25.0 oz

• Hawaiʻi’s Birds, 7th edition, second printing 2022 (Hawaiʻi Audubon Society) 8.2 oz

• Field Guide to the Birds of Hawaiʻi, 1st edition 2020 (American Birding Association, Paine and Paine) 9.1 oz.

Love this article, Chickadee!

" When he started posting his Finch Forecast on an Ontario birding listserv in 1999, other listservs and birding networks started sharing the information. That’s how I learned about it."

Sister Su suggested to me that this sharing should rightly be called, "bird of mouth" information.

Your voice is so calming.

I'm not a taxonomy guy, but I see now after 34 years of apparent lack of notice that you're right, I see the split of Fringillilidae into Emberizidae, the Sparrow family, Fringillidae, finches, and Cardinalidae, cardinals, grosbeaks, and buntings. The Blue Grosbeak is actually a Passerina bunting, the Snow Bunting in the Sparrow family, with the Lark Bunting. But all in the correct families. To add to the confusion, the Fringillidae family is divided into the Fringillinae and Carduelinae Subfamilies. It's a matter of time before common names may be changed to conform, perhaps due to advances in phylogenetics and species concepts and thus our understanding of our subject's evolution.

On the subspecies level, some differences are real, some more political, I'm told by genetist that Red-tailed Hawk subspecies are more imagined than real and at time political, ie variants that people like to name to add to their lists. For eg. also some newer Dark-eyed Junco subspecies. But that has changed changed before as they have been tested in genetic labs. Apparently, mammal taxonomy is still a mess according to some mammalogists...and look at new homicide discoveries recently. So stay tuned.

The book is just in time to start thinking about the holidays. It will make a sweet gift.