Chickens, Part 1.5: Digression to a kin of the chicken

Introduced game birds: to count or not to count

(Listen to the radio version here.)

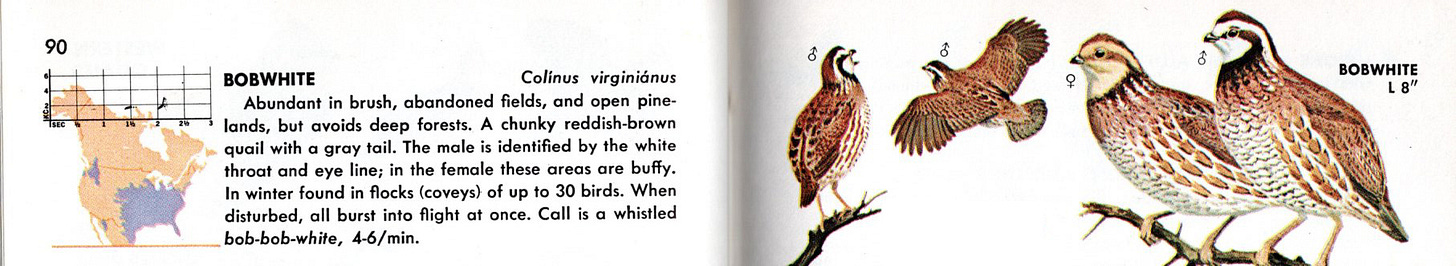

On September 24, 2014, my neighbor called to tell me she had a Northern Bobwhite in her front yard. I quickly got a bazillion closeup photos and entered it in eBird, which accepted my report but doesn’t include it in my official eBird list totals.1 eBird asterisks it as an “exotic escapee,” which is exactly what it is.

My old field guides show southern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan at the northern edge of the range of the Bobwhite. I saw my lifer at the Kellogg Biological Station in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in 1975 when I was taking a field ornithology class, and saw and/or heard Bobwhites on four other field trips during that class, making me think it was a very common bird. During the years we lived in Madison, Wisconsin, I saw them many times at Goose Pond in Columbia County, and once, in 1980, at Picnic Point, my favorite birding spot in Madison.

But already the species was dangerously declining throughout its range. Some combination of habitat changes, over-hunting, and competition with the larger, more aggressive Ring-necked Pheasants that had been introduced to America from China as game birds contributed to the losses in most places, but the fact that Minnesota is outside the natural range of Bobwhites, our winters too severe for this southeastern species, is almost certainly the primary reason they have never maintained a self-sustaining population anywhere in the state.

Based on careful research by T.S. Roberts, Bobwhites were not known to be here at all during pre-European-settlement times. In the 1840s, some were released around Fort Snelling but quickly disappeared. In the 1880s and 1890s, some started appearing in southern Minnesota, but it’s not known whether these were genuinely wild Iowa birds expanding their range as agriculture made grains more available or whether they were introduced birds released in Minnesota, Iowa, or Wisconsin for hunting. For a few years after the Hinckley fire of 1894, Bobwhites showed up on many surveys in Pine County and were assumed to have expanded there from Wisconsin.

In 2004, the Minnesota Ornithologists’ Union justifiably declared the Bobwhite extirpated from the state. But, in my opinion unjustifiably, they no longer accept reports of it anywhere in the state, including where it formerly ranged. It’s quite reasonable to consider the bird I saw in Duluth “uncountable” for precisely the reason that eBird lists—my bird was certainly an “exotic escapee” from a nearby game farm or retriever training club. And as far as birdwatching lists go, it makes sense that any Bobwhite appearing in Minnesota would not be countable until we have solid evidence of a self-sustaining population somewhere in the state.

Oddly enough, MOU does allow people way up here in St. Louis County to both report and count Ring-necked Pheasants seen up here, even though

Like barnyard chickens, pheasants are not native anywhere in the United States. They were released in Minnesota as game birds beginning in 1905, well after the first introductions of Bobwhite;

They are popular game-farm birds that often escape and to this day are still released intentionally here and there in Minnesota;

Pheasants have never historically had a self-sustaining population in the forested northeastern part of Minnesota. T.S. Roberts wrote in 1932 that “their continued existence in the northern counties will probably depend upon frequent restocking,” and the Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas information about pheasants notes, “Scattered breeding records and detections have been reported sporadically in many northern regions of the state, but most or many could be birds released from game farms or by individuals.”

When I moved here in 1981, we could find pheasants in the Duluth harbor where they were clearly dependent on grain spills, but they disappeared never to return after the “Halloween snowstorm” of 1991. In recent years I’ve seen them a few times up in the Sax-Zim Bog. The MOU has no trouble accepting these sightings, though it seems highly improbable that the pheasants found their way to the harbor or the Bog on their own—they must have arrived via game farms or releases the same as my Peabody Street Bobwhite.

People are growing more concerned about the Northern Bobwhite as a once-common bird that is disappearing, and more aware of and committed to restoring grassland habitat.

Organizations such as Quail Forever and The National Bobwhite Conservation Initiative are focusing a lot of resources on restoring populations of this beloved gamebird, so it’s very likely that Bobwhite numbers will start growing in neighboring states and eventually (perhaps already) work their way back to Minnesota. As climate change softens the effects of Minnesota winters, Bobwhites could well become genuinely established in the state.

The listing rules of birding are not very important to me, so I don’t care how illogical it is for Ring- necked Pheasants to be on my county lists while Bobwhites are not. eBird defers to state records committees in deciding what birds are “countable,” but eBird serves scientific as well as hobbyist goals, so they welcome reports of even uncountable “exotic escapees.” During the five summers (2009-2013) of the Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas, participants recorded 4 records of Bobwhite, all “close to the Mississippi River in the dissected uplands that drain directly into the river in Houston, Wabasha, and Winona Counties,” exactly where self-sustaining populations working their way here from Wisconsin or Iowa would most likely appear. As the authors of the MBBA Northern Bobwhite entry note, “Without better monitoring, reporting, and research about the origin of these Bobwhite quail and others in the southeastern region of Minnesota, there is no way of knowing if they are native or released.” I’m glad eBird is doing their best to keep track of them.

The domestic chicken, like the Ring-necked Pheasant and Bobwhite, is a gallinaceous bird. Some chickens do escape farms and backyard chicken coops, but they don’t live long or breed well in the wild in temperate climates, so these feral birds have never established self-sustaining or “naturalized” populations in the United States. Or have they? And are they “countable” anywhere in the States? Tune in next time to find out!

Of the 173 birds accepted by eBird on my yard list, four are flagged as “naturalized,” meaning they arrived in Minnesota following introductions, but unlike my one “exotic escapee,” they’re all still countable. The Rock Pigeon, European Starling, and House Sparrow were brought to America from Europe and quickly spread here. The House Finch is an American species that originated in the southwestern United States and Mexico but became a popular cage bird, sold in pet stores even after the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act made that illegal. Reportedly, some pet store owners became afraid of being fined and released their House Finches in New York City in 1939. Instead of dying out, the birds multiplied, slowly but surely making their way westward, with the first well-documented sightings in Minnesota in Minneapolis in 1980 and then 1983. All four of these flagged but countable species have self-perpetuating populations without human assistance.

While a child growing up in rural MI (closest town was Bellevue...which is situated between Battle Creek and Lansing) I used to call: Bob, Bob White and they would call back but never show themselves...!