Chickens, Part I: Domestication

Southeastern Asian roots for all the world's chickens

(Listen to the radio version here.)

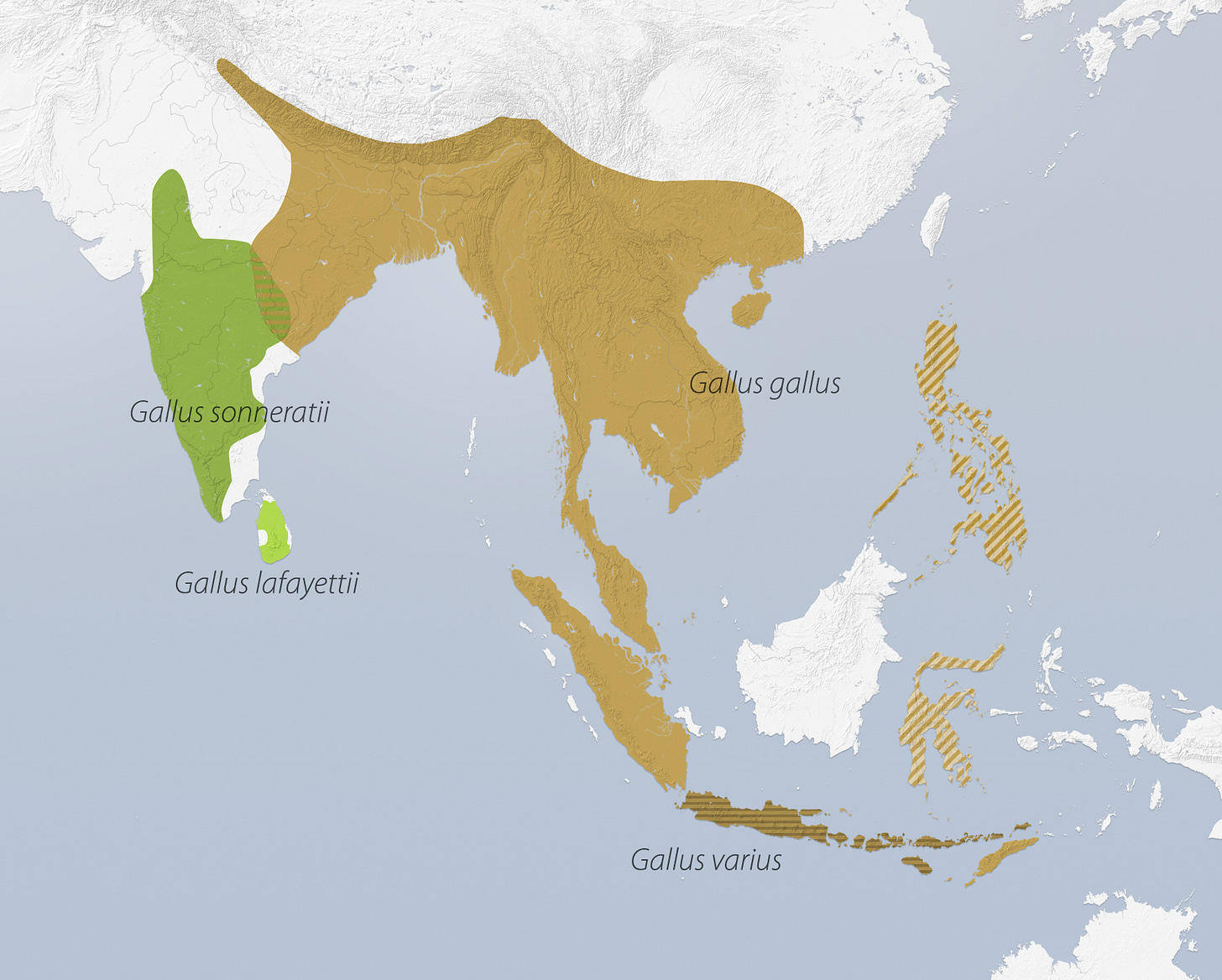

Somewhere between 3,000 and 10,000 years ago, people in southeastern Asia started domesticating junglefowl—tropical members of the pheasant family. Today’s barnyard chickens are essentially descendants of the Red Junglefowl, but also, to a lesser degree, of three closely related species: the Green, Gray, and Sri Lanka Junglefowl. In nature, when any of those four species hybridize, their offspring are generally infertile, like mules, but DNA studies show strands of DNA from the other three species in some chickens. The trait of yellow skin in particular seems to have come from Gray Junglefowl.

A 2022 study suggests that as people started cultivating rice and millet, wild junglefowl started gravitating to wherever the grains were produced or stored, so agriculture may have initiated the process of domestication, and it widened the junglefowls’ ranges.

Chickens are such an important source of meat and eggs that it never occurred to me that they’d been domesticated for any other reason than food production, but I was wrong—the earliest archeological evidence suggests chickens were first domesticated for sport fighting and ritual purposes.1 I guess that makes sense—if the birds were more abundant where rice and millet were grown, they’d have been plenty easy to hunt for food without people going to the trouble of maintaining them in captivity.

Once chickens were domesticated, people could selectively breed them for desirable traits. Some of the most obvious differences between wild and domesticated junglefowl are in feather colors and patterns. Wild Red Junglefowl have the classic red, black and green plumage. Domestic chicken breeds are far more variable, though some bear the classic pattern, too. Wild Red Junglefowl have gray legs while many, but not all, domestic chickens have yellowish legs. One feature that is supposed to be consistently different between wild and domestic chickens is in the length of the last syllable of the rooster’s crow—something I didn’t know about last year in Key West or this year in Kauaʻi, where many of the feral chickens are still genetically related to wild Red Junglefowl. I’ll pay closer attention next week when I return to Key West.

People engaged in cockfighting selectively bred for birds with more aggressive behaviors and more dangerous spurs. Large poultry operations raising chickens for eggs try to maximize egg production. Domestic chickens and wild Red Junglefowl are what scientists call “indeterminate layers,” meaning they keep laying eggs until they have a full clutch (about 6–12 eggs, but there’s a wide margin of error here). If eggs are removed before a female has completed her clutch and becomes “broody,” she’ll keep laying. In one famous and cruel experiment on a Northern Flicker, an indeterminate layer who normally produces 6-8 eggs in a clutch, after a female had laid two eggs, a scientist removed one whenever a new egg appeared, keeping at it until that poor bird had produced 71 eggs in 73 days!

When people raise chickens for eggs, consistently removing the eggs from the nests every day or two, the hens keep laying, usually one per day. Wild Red Junglefowl in natural situations in places where climate favors a single clutch a year would normally produce about 10–15 eggs per year. Once a hen grows broody, she’ll focus on incubating the eggs and then raising the chicks. “Laying hens” in factory farm situations produce 250–300 eggs a year (the record in the Guinness Book of World Records is 371 eggs in 364 days). The birds are bred to be extraordinarily fecund, and their feed is rich in nutrients and calcium, but despite genes and a scientifically developed diet, this level of production rapidly depletes their bodies, giving them much shorter lifespans than hens living more natural lives.

People raising chickens for meat production have selectively bred larger birds, so like domestic ducks compared to their ancestor wild Mallards, chickens are larger than those original Red Junglefowl.

So domestication has changed the junglefowl genome enormously. Chickens sometimes escape captivity and try to eke out a life as wild birds, and in a few places they’ve succeeded well enough to build up sustaining populations. Next time I’ll talk about where this process of feralization has happened in the United States, particularly on Key West, Florida and the Hawaiian Island of Kauai.

I found this out from Eben Gering, a wonderful and approachable scientist who has done extensive work on “feralization,” particularly of chickens on Kauai and in Key West, Florida, and fascinating evolutionary studies on Toxoplasma gondii. The chapter he wrote in a 2020 book, Evolution in Action: Past, Present and Future has the brilliant title: “Time Makes You Older, Parasites Make You Bolder--Toxoplasma Gondii Infections Predict Hyena Boldness toward Definitive Lion Hosts.”)