(Listen to the radio version here.)

Like virtually all Americans, I don’t want drinking water or the air we breathe—my own, my family’s, or anyone else’s—polluted. But I don’t understand a lot about toxic chemicals. I’m probably above average as far as my education goes—I graduated first of 450 kids in my working class public high school Class of 19691, and I took a lot of science classes in college and grad school, including ecology, biology, chemistry, organic chemistry, and both human and avian physiology. To understand how regulations are crafted, enacted, and enforced, I also took a couple of graduate-level environmental law classes.

But like every single person in the country, it’s impossible for me to keep up with all the environmental risks to me, my family, and birds even as year after year, more pesticides, plastics, and other materials are formulated, and more waste material incinerated and dumped in landfills and the ocean.

The Clean Air and Clean Water Acts and FIFRA (the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act) did not itemize every possible contaminant. That would have been impossible then and orders of magnitude more difficult now, considering that more than 800 pesticides are currently registered by the EPA for use in the United States and, according to the Pesticide Action Network, more than 17,000 pesticide products are currently on the market here, some virtually identical to others but with different labeling, some including different combinations of registered pesticides, and some approved through “conditional registration,” a regulatory loophole that allows products on the market quickly without thorough review. More than one billion pounds of pesticides are applied in the United States every year, and that amount is mushrooming because many of our food crops are genetically modified to withstand increasingly heavy herbicide applications as more and more weeds grow resistant.

Pesticides are only a fraction of the dangerous chemicals released into our air and water. Emissions from manufacturing and power plants, refineries, and incinerators; waste byproducts from manufacturing all kinds of chemical products; and those chemical products themselves can be toxic. How could anyone possibly keep track of all this?

The genius of environmental legislation enacted in the 1970s was to empower the brand new Environmental Protection Agency to make environmental assessments about a whole panoply of potentially toxic chemicals, setting national standards for how much of any toxin can be released into the air or water. This is exceptionally complicated. I’ll give just one example:

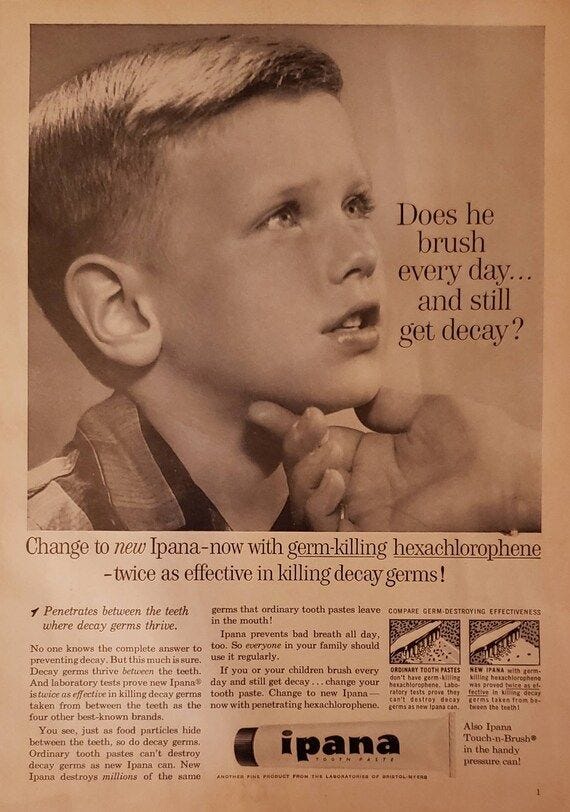

In the late 1950s, hexachlorophene was added as an ingredient to Ipana toothpaste, Dial soap, Mennen Baby Magic Bath, some baby powders, and many popular skincare products. A phrase from one 1959 Ipana toothpaste commercial is still stuck in my head: “It’s got hexa- hexa- hexachlorophene!”

Then, in 1972, a batch of baby powder with hexachlorophene in France killed 59 babies and caused severe neurological damage to several hundred other babies, causing an international furor. And hexachlorophene was involved in 15 American deaths, too, leading our Food and Drug Administration to prohibit its use except in very small concentrations in certain pharmaceuticals.

During the time hexachlorophene was used here, a Missouri company making it had to deal with a very toxic byproduct of the manufacturing process—dioxin. The company was supposed to send the waste sludge to a facility in Louisiana for incineration, but in 1971, to save money, they passed the buck to one chemical disposal company, which subcontracted it to others. One of the subcontractors mixed six truckloads of the toxic sludge with used motor oil which they sprayed on dirt roads and other surfaces in several areas to control dust. After spraying it on some horse arenas and stables, birds started dropping dead from stable rafters and horses developed sores and started losing hair. On one farm, 62 horses died or had to be euthanized because they’d become so emaciated, and the horse owners and their small children became ill.

The CDC tracked the illnesses to that one hexachlorophene plant and its contractors and subcontractors. Ultimately, one small city, Times Beach, Missouri, ended up so badly contaminated that it was completely evacuated and eventually disincorporated, and became one of the first Superfund sites.

The EPA’s Superfund program is responsible for cleaning up some of the nation’s most contaminated land and responding to environmental emergencies, oil spills and natural disasters. Currently, there are 1,340 Superfund sites in the National Priorities List in the United States, 39 additional sites have been proposed for entry on the list, and 457 sites, including Times Beach, have been cleaned up and removed from the list.

The hexachlorophene/dioxin connection is an old example. Last summer when he was 2 years old, my grandson knew that before we could take a walk or play outside each morning, we had to check the air-quality index. Walter is a child of privilege—the houses he plays in have high-quality air filters. How about the many children whose families don’t have them? Cleaning up all these environmental messes, and preventing as many as we can before they become dangerous, is what we count on the EPA’s scientific and administrative staff to do—vital work that we all depend on for our lives, liberty, and pursuit of happiness whether we’re 2 years old or 72.

The extraordinary popularity of the first Earth Day put a lot of pressure on the Nixon administration. On July 9, 1970, less than three months after that inspiring and empowering day, Nixon proposed consolidating the piecemeal government pollution control programs into a new Environmental Protection Agency. That summer, the House and Senate approved the proposal. In its first year, the EPA had a budget of $1.4 billion and 5,800 employees. At its start, the EPA was primarily a technical assistance agency that set goals and standards, but soon Congress gave it regulatory authority, too.

I remember the elation I felt when the EPA opened for business on December 4, 1970. Soon the Cuyahoga River would no longer catch fire. Birds would stop dying from the insecticides that took out way more than the insect pests they were targeting. Gary, Indiana would stop smelling so bad that we’d quite literally be gagging whenever we drove between Chicago and East Lansing.

I felt as relieved and joyful as Princess Leia at the end of the first Star Wars movie.2 Our long national nightmare would soon be over. Of that I was absolutely certain.

Russ was in my class and got straight A’s. I got a few B’s. But they changed the class ranking system that year. They first of all started giving difficult courses extra weight, multiplying college prep ones by 1.2 and advanced ones (we didn’t have AP at our school) by 1.4. This made a kind of sense, rewarding kids academically for taking harder classes, but instead of averaging our weighted grades, they added them. Russ and I took the exact same English, science, math, and social studies courses, but I took four years of Spanish while he took just 3 years of German, a far more difficult language. And I took four years of choir while he took only 2 years of band. So although I think he deserved to be first (his straight A’s weren’t merely A’s, but often curve-busting A’s) our school records really do show me in that position.

I realize the first Star Wars movie didn’t come out until seven years later. But looking back on that triumph half a century later, yep—I felt as relieved and joyful as Princess Leia.

Makes me wonder how anyone now days keeps from getting cancer, etc....