(Listen to the radio version of the first half here, and the second half here.)

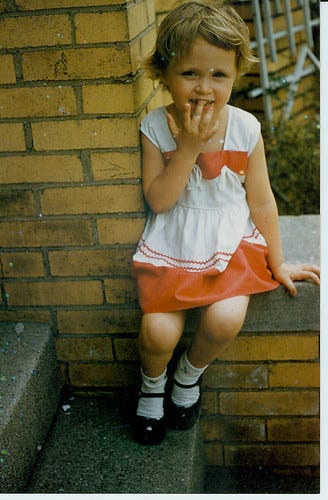

I was exactly the kind of little girl who needed a pet. I yearned for a puppy who would love me unconditionally, but that wasn’t in the cards. If I couldn’t have that, the next best thing would be something I could love unconditionally that at least wouldn’t hurt me. While we were still living in Chicago, I spent a lot of time watching House Sparrows, pigeons, and robins, but they were wild and free, and needed their friends and families—I would never have dreamed of making one of them into a pet. My Grandpa had pet canaries that I loved dearly, but his house was quiet and peaceful. Even if I could have managed to get a cage and food and a real live canary or parakeet, it would not have lasted long in the noisy chaos of our two-flat apartment.

I spent hours riding my squeaky tricycle back and forth along our block, and I quickly learned that I had to be very, very careful after it rained, because worms would be wriggling about all over the place, and I couldn’t bear the thought of squishing them. I got into the habit of picking them up and placing them in the grass. Some were already partly squished. My mother told me those were doomed, but if they were wiggling at all, something impelled me to set them in the grass.

I was four, exactly my grandson Walter’s age now, when we moved to Northlake. I still loved riding my tricycle along the sidewalk, but now after a rain there were even more worms to protect. I kept moving the healthy ones to the grass, but when I found an old leaky dishpan, I filled it with dirt from behind the garage and started putting the injured worms in it. My mother ridiculed my stupidity, and some of the worms died. But when I rooted through the dirt of my worm “hospital,” I’d find healthy worms in there, too. When the dirt started getting dry, I sprinkled water on it, and every now and then I added fresh dirt on top—I didn’t know how else to feed them. I can’t say they were happier in the dishpan than they would have been in the wild, but every now and then I’d discover a bunch of new, tiny worms. When it seemed like they might be getting a little crowded, I’d let the whole mass go behind the garage (except for recently hurt ones) and start over again. At some point, I tied our wagon to my tricycle and pretended that was my worm ambulance. I made emergency runs around the neighborhood after just about every rainstorm.

When I was five, an older boy across the street made me a little cage and gave me a white mouse whom I named Stuart.

I could make eye contact with him, unlike my worms, and I certainly loved him more, but no way could I abandon my worms. When I was in third grade, we finally got a dog—a beagle puppy we called Princey—the first pet who seemed to love me as much as I loved him. But I still had to keep my little guys safe.

One spring day in fifth grade (and yes, even at that point I was rescuing worms after every rain), Mr. Borkowski announced that we were going to dissect earthworms in class. I was thrilled about the prospect: I thought dissecting might reveal the “inside story”—the secrets of worm bodies that would help me save more of the poor squished ones—so I was very excited about doing this. I wasn’t the least bit squeamish. But….

Mr. Borkowski told us that we’d each need to bring in our own worm—the bigger, the better. I knew I couldn’t bring in any of my personal earthworms or one from behind the garage, but figured if I could dig up a “stranger” somewhere, maybe I could muster some “scientific detachment” (I don’t know where I’d picked up that expression, but it seemed important). I tried to dig some up in a neighbor’s garden across the street, but every single worm I picked up wiggled in my hand in a way that told me it very much needed to stay alive. I didn’t know how to pick out one that wouldn’t mind giving up its life for science.

Finally, I went to Mr. Borkowski and poured out the whole story. My whole family had always ridiculed my concern for earthworms, so it was a leap of faith and trust that allowed me to say anything about it to my favorite teacher. And Mr. Borkowski—that 24-year-old inexperienced teacher with just an associate degree—instantly rewarded that faith and trust. He looked at me with his gentle, serious eyes and said, “You know what I’ll do, Laura? I’ll find you a worm that’s already dead.”

I felt inexpressible relief, and that seminal moment remained with me for life. Imagine the level of empathy required to respond like that without even a trace of amusement in his eyes! Over time, I grew to appreciate his instantaneous response as one of the truest examples of empathy I would ever witness. That moment was the reason I dedicated Sharing the Wonder of Birds with Kids—my book that won the National Outdoor Book Award for 1997—to him:

This book is dedicated to Arthur Borkowski, my fifth grade teacher, who taught me to open my eyes without closing my heart.”

Nobody taught me empathy, which seems rather obviously to be an innate human impulse like hunger, aggression, greed, anger, and love. The amount of empathy, along with other natural desires and impulses, varies among individuals, and like hunger, aggression, greed, anger, and love can be nurtured or squelched by parents, teachers, and other people we associate with in early life and the society we find ourselves in.

Like other natural impulses, empathy is seen in other social creatures, too. Even if they get no food rewards, rats spend time and effort releasing other rats from traps, including when a trapped rat is certain to take favorite treats that could otherwise be eaten by the free rat. (Read the 2011 story from the National Institutes of Health here.)

I once came into my home office to find my licensed education Blue Jay Sneakers had escaped from her cage.

I don’t know how many mealworms she’d already eaten from the bucket, but when I came in she was loading up her gular pouch with mealworms that she delivered to BJ, another Blue Jay more securely enclosed in his cage.

There’s a documented record of a male Eastern Screech-Owl, who had lost his own mate and young, brooding a batch of baby flickers whenever the parents were out of the cavity, and even trying to feed them pieces of a mouse, though the baby flickers couldn’t figure that out—parent woodpeckers insert their long bill down their babies’ throats and regurgitate food deep into the throat. The owl could easily have killed and eaten the baby flickers, but even though their natural responses to him were not at all what an owl would expect from its own young, his nurturing impulse was stronger than his hunting instinct in that situation.

The charming habit of waxwings to pass a berry back and forth to one another before one of them eats it must give some kind of innate reward—otherwise each bird along the line would eat every berry that came into its mouth. Strengthening social bonds like this must be a reward in and of itself, but oddly enough, after rehabbing a Bohemian Waxwing one winter, I realized that that generous impulse had a tangible reward, too. Waxwings were pigging out on mountain ash berries in my tree while I was rehabbing one, so I picked berries from that same tree to feed to the waxwing. It swallowed them instantly, not having anyone to share them with. But 15 or 20 minutes later, those berries came out the other end pretty much undigested. When I rolled the berries between my thumb and index finger to soften them, they clearly were more completely digested. I suspect waxwings passing berries back and forth in their beaks soften them (especially before hard freezes break up the waxy coating), strengthening a flock’s social bonds even as they weaken the berries’ outer skin.

From my earliest memories, my parents and siblings all ridiculed my “rescuing” worms on the sidewalk, but the gratification I felt for helping the poor little guys more than made up for that. Just about everyone I told about my worms laughed—usually not in a mean way, but certainly not in a way that might have nurtured my sense of empathy. That’s why I’m pretty sure it’s a simple human impulse—clearly more heavily expressed in some than others, but it obviously benefits human families, neighborhoods, and communities, and impacts us all as a social species.

There is no verification that she really said this, but Margaret Mead is credited with answering a question after a lecture about what she considered the first sign of human civilization—a healed human femur. Broken leg bones in animals can’t mend themselves. Mead or whoever originally said this explained that a broken femur could only be healed if the injured person was protected, fed, and cared for by another person. Civilization requires people to be able to count on one another’s help.

Empathy and caring for others beyond self-interest was also behind Jonas Salk’s not just developing the polio vaccine but giving the patent to the American people when he could have profited enormously.

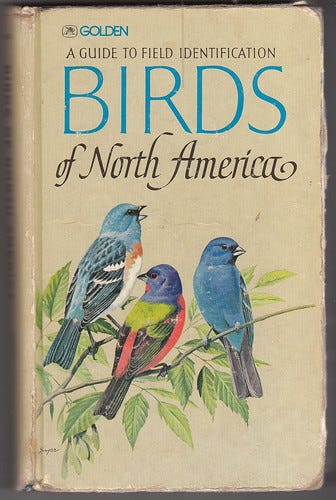

My personal hero, Chandler Robbins, told me he earned enough for himself and his family with his job in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and so he didn’t need the money he earned as author of the Golden guide Birds of North America. He donated all of his royalties, as they came in, to people and organizations who needed equipment, training, and other support for their work in bird conservation in the American tropics.

Chickadees all work hard to amass large caches of food, but when one chickadee’s hoard is lost—say, if the birch tree it was using topples in an ice storm—other chickadees don’t mind it raiding theirs. REAL wealth is measured in what we can afford to share, not what we hoard away.

Dissecting that worm in fifth grade turned out to be very interesting but ultimately disappointing. I learned the name for the thick, smooth part of the body—the clitellum. I’d sort of noticed that if a still-wiggling worm was squished on the shorter part of the body, it invariably died, and now I learned that that part of the body in front of the clitellum was where the worm’s mouth and hearts and the main parts of its digestive system were. The longer part behind the clitellum was apparently more able to be regenerated. But dissecting did not teach me how to become a worm veterinarian—indeed, after being so careful making the incision to look inside, I was sorely disappointed that we didn’t learn how to suture it back up. It’s probably just as well—otherwise, one day some future anthropologist might use sutured-up earthworms as evidence of … well, something.

Laura, even though I've been a fan of your writing for years, you continue to amaze me with the power of your work ... essays like this one, with so much heart and intelligence. I hope you'll collect some of your best in an anthology, to make them available for future generations.

"We all do better when we all do better." - Paul Wellstone