Getting away with murder, Part 5

In this final post about the BP spill, I talk about the slippery slope from courage through silent resistance, hanging on for survival, and cowardice, all the way down to complicity.

(Listen to Part 1 of the radio version here, and Part 2 here.)

During the time I was writing about the Gulf oil spill in 2010, I received an anonymous email from a hotmail account reminding me that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) had the power to rescind my permit to keep my education owl, Archimedes, if I wasn’t “careful.” Without my permit, he could be confiscated and euthanized.

Then I got a phone call from a person I very much respect at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology telling me that, because some people were associating my name with the Lab, someone at the USFWS or U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) had told them to ask me to tone down my postings. I’d left my job as Science Editor at the Lab a few days before the Deepwater Horizon explosion and never suggested that I was collaborating with or still associated with Cornell. The Lab did not pressure me in any way to stop writing about the spill, though it sounded as if they themselves must have been pressured to call me. I did promise I would publicly correct any errors I made in any posts, but that wasn’t an issue.

The Cornell Lab, along with other organizations, produces an important State of the Birds report every few years in collaboration with the USGS and USFWS. And the Lab, like virtually every non-profit and educational institution that bands or satellite-tracks birds or other wildlife or conducts research on marine life, must have various federal permits from the USFWS, USGS, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Navy, and/or other governmental entities—permits that can be revoked at any time at the discretion of those agencies.

These kinds of projects are a key element of many organizations’ and research institutions’ fundamental mission—the reason for their existence. My friend Marge Gibson, director of REGI, a state-of-the-art wildlife rehabilitation center, was told outright by a USFWS employee that her rehab and education permits would be revoked if she went anywhere near the Gulf, so I know that the threat was real. The Cornell Lab and other research and educational organizations would have risked virtually all their ongoing work, and even their existence, if they didn’t abide by the 5-year moratorium suddenly imposed to delay the publication of ANY studies, videos, photos, or observations of oiled wildlife in the Gulf without approval. Too much was at stake to resist publicly, but the Lab and others continued to collect data that would eventually be publicized.

Because this really was an existential threat, their silence was not cowardly, much less complicit. My mantra since college has been “To sin by silence when one should protest makes cowards of men,” but “cowardice” can only be understood in the context of a long slippery slope starting at courage and descending to complicity. In the ongoing war to protect birds and our environment, surviving to fight another day is a valid strategy.

The American Birding Association (ABA) was the one organization that showed astonishing courage during this horrible time. They supported Drew Wheelan and published his accounts on the organization’s blog even in the face of attacks on his veracity and complaints from some of their own members. Fortunately, ABA wasn’t facing an existential threat—it needs no federal grants, permits, or collaborations to fulfill its mission, which is simply to help people find, learn about, and enjoy birds.

Had every educational institution and non-profit organization studying birds on the Gulf joined forces to publicize, or at least leak, information about everything going on, it’s still doubtful they could have mustered the massive public support the Obama administration would have needed to defy BP’s dictates. BP had a wealth of lawyers to fight the government every inch of the way, professional scientists on their payroll who’d be willing to deny the truth, and the legal right to clean up their mess the way they wanted to. I think Cornell and the American Bird Conservancy did as much good as they could.

One organization went much further than simply staying mum during the moratorium—it publicly parroted BP’s ridiculous claims about the oil disappearing and the spill not being so bad, and personally attacked, in a major public forum, Drew Wheelan, the most courageous individual speaking out about the spill’s effects on birds. This organization—ironically, the one whose name is most associated by the American people with bird protection and conservation—rolled straight down that slippery slope from courage and quiet resistance right past trying to survive and downright cowardice. This organization kept sliding, down, down, all the way to complicity.

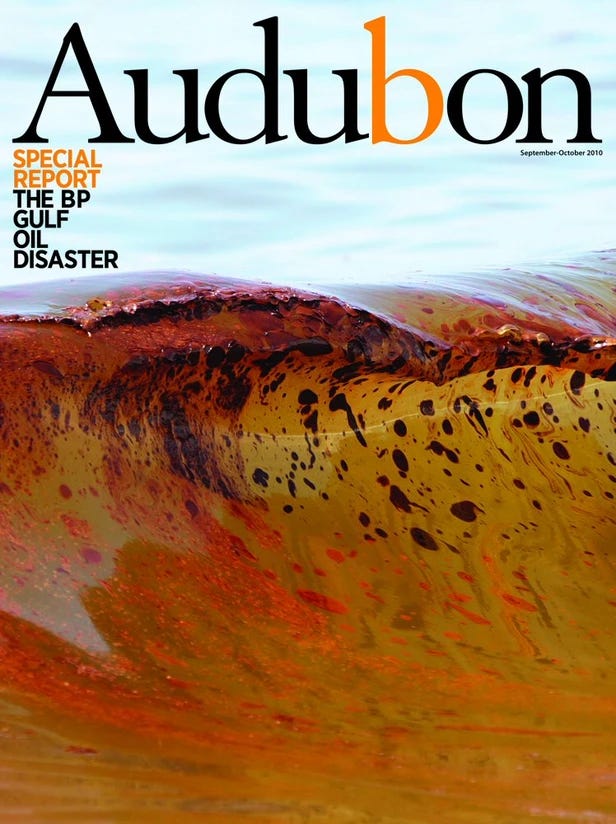

The cover story for the September–October issue of Audubon, the award-winning publication of the National Audubon Society, was a long and detailed “Special Report: The BP Oil Disaster,” written by one of their most prominent writers, Ted Williams, who has a long and storied career as a conservationist and a curmudgeon. (The article is no longer available online. My quotes from it are taken from my September 3, 2010 blogpost about it.)

Williams’s regular Audubon columns, titled “Incite,” were often written in an angry Lewis Black style. He was extremely vociferous about one important issue facing birds, domestic cats, but seemed to think most of the major environmental battles had already been won, by his generation. He smugly wrote in his November-December 2004, column for Audubon (no longer on Audubon’s site that I can find, but quoted here):

I envy young environmentalists of the 21st century, but I feel bad for them, too. They don’t know what it feels like to win big against seemingly impossible odds. When I started out, America and the world were environmentally lawless. There was no Endangered Species Act, no Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, no Clean Water Act, no Clean Air Act, no National Environmental Policy Act, no National Forest Management Act.

Thank goodness our serious environmental problems are over, right?

When Williams was sent to the Gulf by Audubon, he limited his entire “investigation” to places BP staff and contractors brought him to, exactly as if he were doing public relations for BP, not trying to uncover the truth. When he lambasted a “toxic gusher, one of misinformation,” he wasn’t talking about the many BP lies swirling about. No—he repeated scientifically discredited information as fact, such as when he compared this disaster to the Exxon Valdez spill:

Deepwater Horizon oil is different. It is highly volatile, and nearly half evaporates immediately. In the intense heat, bacteria consume other fractions. Also, the leak is almost 50 miles at sea, giving dispersion and natural breakdown processes more time to kick in.

He also gushed, “Much has been learned about boom laying and skimming, and operations are massive and intense.” Reading that brought to my mind the badly oiled Black-crowned Night-Heron I'd seen sitting on oiled boom,

and the prisoners on work release tossing small shovelfuls of oiled sand into plastic bags.

I could feel how hot the water along shore was when I visited West Ship Island in Mississippi on August 1, 2010, but it was easy to research how further out from shore, the temperature drops precipitously as you move down the water column from the surface to the depths. Even during a hot summer, the deep water in the Gulf where the oil originated can be 40–30º F.

Drew Wheelan had posted a lot about how desperately qualified volunteers were needed. Ted Williams dismissed that:

Audubon is seeking volunteers experienced in handling seabirds and asking them to sign up with response leaders. But at this writing there aren’t so many oiled birds that state and federal recovery personnel can’t handle the job. Therefore, qualified volunteers are being told to stand by in case they’re needed. The very last thing Gulf Coast birds need are well-meaning amateurs crashing through nesting habitat.

Audubon was criticized widely for not galvanizing the many qualified and professional rehabbers rehabbers who’d volunteered but were turned away. Williams defended this:

It’s hard to do nothing when the world is yammering at you to do something—anything, even the wrong thing. This was a lesson I relearned on the humid, 100-degree morning of June 15 when I visited bay islands with Reid and his Audubon colleagues Melanie Driscoll, director of bird conservation for Audubon’s Louisiana Coastal Initiative, and Karen Westphal, Atchafalaya River Basin program manager.

The saddest scene we encountered—up close, from Wolkart’s 24-foot Ranger Bay boat—was the royal tern colony on Queen Bess Island. Ringing the oil-stained mangroves was red hard boom and, just inside, white sorbent boom. Such barricades offer partial protection at best. Only about 10 of some 300 adults had been oiled, but virtually all the estimated 150 chicks were covered. “If we do nothing, they could die,” said Driscoll. “They’re at risk of overheating and sunburn, hypothermia if they get wet. But if we evacuate them, they won’t be taught to fend for themselves, and they’ll probably die, too. The thought is that now that they’re close to molting they’ll drop their oiled feathers and a few will make it. I don’t know if that’s a good theory, but we’re in a situation where there’s no good decision. The best decision is not to have an oil spill.”

Let's put aside the issues of compassion for suffering birds, how the importance of every individual bird rises as its population declines, and how much progress in bird rehab and captive rearing we've made since the days of the Exxon Valdez. Let's just simply consider Melanie Driscoll’s question about whether the oiled young birds had a higher chance of survival if they were left or if they were retrieved for rehab. At the very least, shouldn't scientists have retrieved some of those chicks on some of those islands to learn, based on actual data, which approach worked better? That is what science is about. But had any of those birds been captured, BP’s “Consolidated Oiled Wildlife Report” totals would have been higher. So every single one ended up dying, and then, because everyone was prohibited from entering the islands (because it might disturb nesting birds!), not one of them was retrieved, and not one was included in BP’s official count of oiled birds.

Ted Williams’s advancing BP’s take on the oiled bird front without talking to professional rehabbers who’d spent long careers capturing and treating oiled birds was egregiously poor “reporting,” especially unacceptable for an organization whose name is synonymous with bird conservation for so many Americans. It wouldn't have taken much investigating for Williams to learn what the St. Petersburg Times reported in late August under the headline: Bird Rescue Experts Kept on Sidelines after Gulf Oil Spill. (This is yet another article that is no longer available online.) And even though he wrote about Drew Wheelan, and quoted him, not once did Williams try to talk to him, either. Just about everything Ted Williams wrote about Drew was taken from watching him on TV! He wrote:

In an interview with CNN’s Gary Tuchman, the American Birding Association’s Drew Wheelan declared: “I cannot see any reason why they would not want as many people here as possible.” And in a later CNN broadcast he and Anderson Cooper spoke of “experts” who supposedly possess the power to pluck birds from the firmament, a feat impossible for any human save Harry Potter. [My emphasis because I was so gobsmacked to imagine Williams has never once observed bird banding or watched expert rehabbers retrieve oiled birds in the aftermath of other oil spills. Harry Potter is hardly the only human who can catch birds.]

Cooper, goosing Wheelan along: “…. Basically, you’re saying they’re just going after the birds who are completely covered in oil and unable to move, and these are the birds that are likeliest basically to die…So birds that maybe have less oil on them and can fly, they’re not going after those birds because it’s too much effort and too difficult.”

Wheelan: “Yeah, they just don’t have any expertise in that area. . . . There’s no reason why there shouldn’t be 50 people down in Grand Isle . . . going out at dawn, trying to capture these birds.”

Cooper: “It seems there are a lot of volunteers and a lot of bird experts who would love to be down here and love to be helping.”

Wheelan: “Absolutely. . . . I know the Audubon Society has over 17,000 people that have signed up to volunteer on this effort, and so far they’ve not received a single phone call. . . . They just don’t want to allow any help.” (Wheelan issued a retraction on his blog after Audubon explained to him that the best way volunteers can help is to wait patiently until they’re contacted.)

That parenthetical last sentence is an outright lie. Right after the article came out, Drew Wheelan wrote on Facebook on September 2:

I did not retract anything I wrote about the Audubon Society and their volunteers. They had many opportunities that could have helped down here that they let slip through their fingers. The blame is really on [BP’s] Incident Command for not identifying areas of need and allowing qualified people to help...

Audubon has had every opportunity to work as stewards to protect beach nesting colonies in Louisiana, and I was specifically told by Melanie Driscoll to lay off the issue, as she had it covered. They did nothing. [Nesting bird] Colonies from the Chandeleur Islands to the Timbaliers have all been impacted negatively by clean up response, and LDWF [Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries] and Audubon never did a thing to help…

There were many different ways that even untrained volunteers could have been used without compromising cleanup or responsible, legal wildlife rehab protocols. For example, teams could have been sent out on prescribed routes to check, at a safe distance, the boom around vulnerable islands to alert cleanup response teams where boom needed to be replaced or better secured before it got washed onto islands. When I was in the Gulf at the end of July, over three months after the BP explosion, a crew was putting in vertical structures to hold the boom in place—something that should have been done much, much earlier, and exactly the kind of task that requires hard work but minimal skills.

Ted Williams obligingly repeated BP's "nothing to see here, folks!" message, writing in Audubon:

Due to the nature of the oil and the monumental cleanup effort [my emphasis], visible damage was not as bad as the public imagines or the media have depicted. Occasionally we smelled oil, but although goop and tar had washed up elsewhere, we saw only light sheens.

Where I was in July and August, there wasn’t much to smell in most areas, but after standing on one oiled beach for 20 minutes or so, I felt woozy and faint without smelling anything. By his own account, Williams was not exposed to any oiled beaches. Beginning in May and sticking it out for months, Drew Wheelan worked tirelessly in Grand Isle and other places in the Gulf virtually every day except when he developed pneumonia. He was operating on a shoestring, even mostly sleeping in his truck, doing what Ted Williams once did so well—speaking truth to power. Not one word that Drew Wheelan wrote or spoke was in service of any agenda except to present the truth about what was happening to birds as a result of the oil spill. He saw a lot of things that were being done badly, and a lot of things that badly needed being done, and wrote about them with charmingly unfiltered forthrightness.

I returned home after spending time with Drew and seeing with my own eyes so much that he’d written about. I can’t express how disillusioned I was reading that “Special Report” in Audubon targeting not the corporation that caused the biggest oil spill in history but the one young environmentalist of the 21st century who most exemplified the standards Williams used to stand for. Williams was doing his very best to prevent Drew Wheelan from ever knowing “what it feels like to win big against seemingly impossible odds,” with the full support of National Audubon, using their magazine as his megaphone. So I quit Audubon1 and rejoined the American Birding Association.

I rejoined Audubon several years later, but gave up on them again because of their new project promoting the building of more than 200,000 miles of new, above-ground transmission lines wanted badly by energy corporations. Audubon’s claim that this will boost clean energy isn’t borne out by the facts, as Exxon Mobil and other energy corporations are proving right now. (Gift Link to the New York Times article from November 18, 2024, “Why Oil Companies Are Walking Back From Green Energy.”) I continue to be a happy member of the American Birding Association.

Thank you again, Laura, for your clear-headed insights. We who love birds and believe in their inherent right to protection and rehabilitation from human-caused harm; we who respect the importance of the collective ecosystem services they provide and who deeply appreciate the intrinsic beauty of their mere existence in our world; we who grow tired of the always uphill battles and two steps back; we need to breathe the fresh air of your words, catch our breath, and keep taking those seemingly futile single steps forward…no matter what.

I ditto Robert Mulvihill's comments...especially our need to breathe the fresh air of your words Laura!!