(Listen to the radio version here.)

At some point between 1219 and 1266—that is, about 800 years ago, more than two centuries before Columbus got lost—chickens found their way to some uninhabited islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and settled in. They’d traveled quite a way—the nearest land masses where chickens could be found back then were another island chain called the Marquesas (French Polynesia), 2,000 miles away, and Japan, 3,800 miles away. (North America was 2,400 miles away, but chickens had not yet arrived there.) Chickens couldn’t possibly fly, swim, nor walk such a distance. They traveled to Hawaiʻi effortlessly and in style, in the canoes of the first humans to arrive on the islands.1 Those humans called the chickens moas.

As far as humans go, the Polynesians had Hawaiʻi pretty much to themselves for over 500 years, developing the unique cultures and languages defining the settlers as Native Hawaiians. Then, in 1778, Captain James Cook became the first recorded European to reach the islands, and nothing was ever the same for the chicken or human Hawaiians. An influx of Europeans and Americans quickly arrived, and the United States annexed Hawaiʻi in 1898.

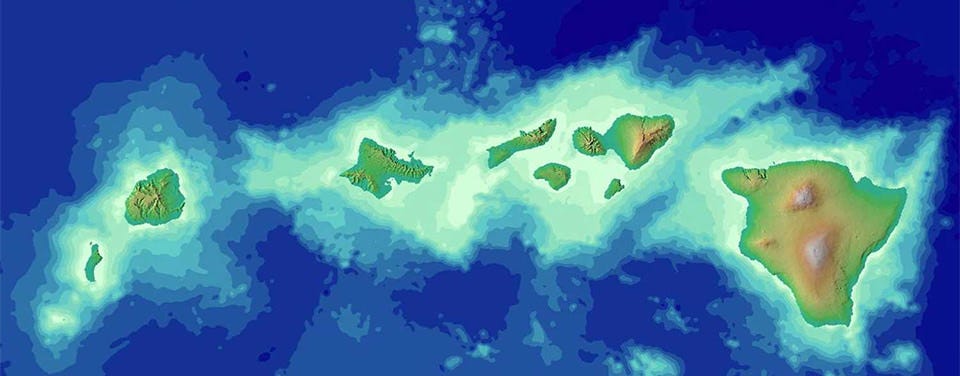

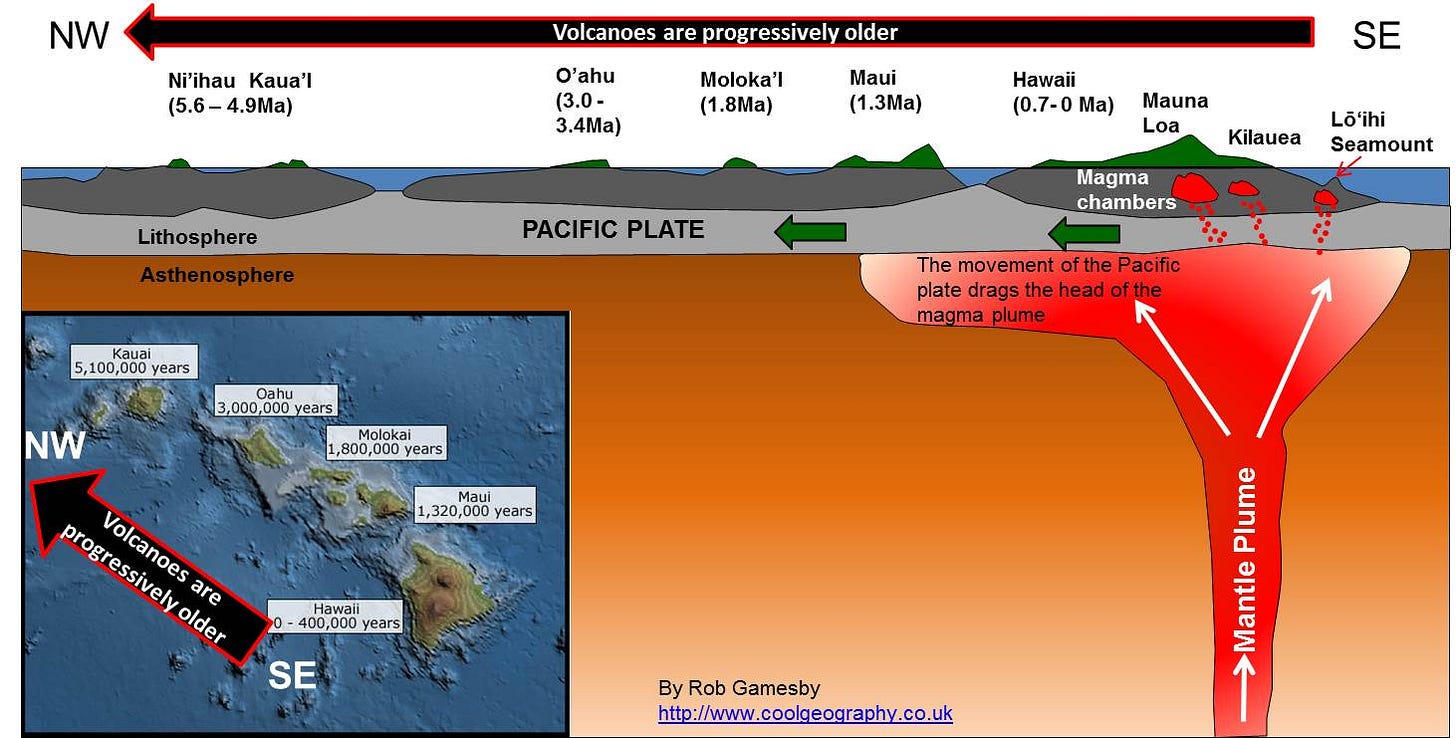

Of course, Hawaiʻi had had itself pretty much to itself for many years, not just as far as chickens and humans go but as far as any living thing—plant or animal—goes. A “hot spot” in the Earth’s mantle beneath the middle of the Pacific Plate, oozing magma, formed an island, Meiji, 80 million years ago. (The Earth itself is about 4.6 billion years old.) That hot spot, still ever active as the Pacific Plate slowly moves (about 3.5 inches per year), ultimately formed the 132 islands, atolls, reefs, shallow banks, shoals, and seamounts of the Hawaiian archipelago. Those visible islands stretch about 1,600 miles between the Kure Atoll in the northwest through the island of Hawaiʻi in the southeast, but if we include the original “seamounts” (volcanoes on the seafloor that don’t reach the surface or whose tops have eroded to below the surface) starting at Meiji, the hot spot’s creations stretch 3,800 miles. Mejii, which originally emerged roughly where the Big Island is today, is now located off the coast of Siberia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. A seamount called Kamaʻehuakanaloa (formerly Loihi), on the flank of Mauna Loa off the southeast coast of the Big Island, is the literally up-and-coming next island in the chain—an underwater volcano with the erupting summit still almost 1000 meters beneath sea level.

The Kure Atoll, the oldest in the island chain we see today, formed about 30 million years ago, long after the dinosaurs were extinct. Of the major Hawaiian Islands, Kauaʻi is the oldest—about 5 million years old. Oʻahu is 3–4 million years old, Molokaʻi nearly 2 million years old, and Maui and Lānaʻi 1.5 million years old. The youngest is Hawaiʻi Island, just half a million years old and still forming via active volcanoes. Kamaʻehuakanaloa began forming about 400,000 years ago but isn’t expected to emerge above the surface for another 10,000–100,000 years, or even a million years depending on who you talk to, so don’t hold your breath.

At first the islands were nothing but spewing lava and molten lava fields, cooling and hardening between eruptions. But the hot spot kept spewing, the Pacific Plate kept moving, islands kept forming, and little by little, spores of algae, mosses, and ferns, and seeds of other plants, blew in or washed up onto the shores.

Sandy beaches formed here and there on the coasts, in part from black volcanic rock eroding but also as shells, coral reefs, and other hard parts of marine organisms broke down and washed ashore.

Some of the seeds that found their way to Hawaiʻi early on belonged to the genus Metrosideros. These lightweight seeds are easily borne on winds but are also able to germinate after being submerged in salt water for up to 30 days. Trees in this genus are often found as pioneer trees on lava flows and mountain ridge, and some of them evolved into Hawaiʻi’s state tree, the ʻōhiʻa lehua, found nowhere else on the planet, and which once covered 80 percent of Hawaiʻi’s native forest. ‘Ōhiʻa lehua once grew from sea level to the tree line.

You can’t have soil without plants, but over millions of years, as ʻōhiʻa lehuas, lichens, and other plants took root in the lava fields, their growth helped to slowly break down the upper layers of rock which could mix with organic matter from leaf litter and dead plants to produce soil, allowing many other plants to take root.

When the islands were first forming, before many plants could have taken root except along shorelines, no land birds who managed to find their way to Hawaiʻi could have survived long. But seabirds such as albatrosses, petrels, shearwaters, and certain terns spend their entire lives at sea, getting all their nutrition from the ocean. These birds need land only as a substrate for their nest. As one parent stays with the nest, the other is getting food at sea. Terns fly to the nest frequently, bringing small fish to their chicks and sometimes their mate. Many other seabirds swallow their catch and then regurgitate a portion of it to the chick at the nest.

For hundreds of thousands of years, Hawaiʻi was ideal for these nesting seabirds, with no mammalian or reptilian predators to harm their young. Their droppings and any eggs, chicks, or adults killed by accidents, storms, or disease contributed more organic material, accelerating soil formation.

As sand and then soil formed, more and more shorebirds and waterfowl who found their way to Hawaiʻi could find food along the shores and sometimes even away from the shore. Over tens of thousands of years, some plants and birds were evolving to thrive in the unique Hawaiian environment. Large numbers of Pacific Golden-Plovers (kōlea) and many Bristle-thighed Curlews (kioea), both which breed up in Alaska, found Hawaiʻi the perfect place to spend winter.

A flock of Canada Geese survived and stayed rather than trying to fly so far back to North America. They fed on fruits, leaves, seeds, and grasses, evolving, little by little, into the Hawaiian state bird, the Nēnē.

Nēnēs can swim and fly, but not needing to fly long distances, their wings are shorter than those of Canada Geese. Because they spend so much of their lives walking on lava fields rather than swimming, the webs between their toes are greatly reduced and the toes and claws stronger than those of their ancestors.

Hawaiʻi became home to many birds, including geese and rails—that over thousands of generations lost the ability to fly. There probably wasn’t a single reason for this, but factors that could have contributed included the lack of predators so that flying to escape danger was no longer critical, and the high winds on oceanic islands that could have plucked birds up and carried them away when they were simply stretching their wings.

When birds, lost or now regular migrants, arrived, some of them still had seeds in their gut. Now that some of the islands had soil, these seeds could take root, increasing plant diversity. At some point a flock of finches, most likely relatives of what are now America’s Pine Grosbeaks or Eurasia’s rosefinches, got lost over the ocean, perhaps borne by a big storm. However they found the islands, they found ways to get food from plants entirely new to them, and evolved like a colorful version of Darwin’s Finches into amazingly varied species.

By the time the first chickens and their attending humans arrived, Hawaiʻi was home to at least 142 endemic species of birds—a veritable paradise. The chickens and humans thrived, but their arrival marked the beginning of the end for at least 95 of those 142 bird species, with several of the survivors today at the edge of extinction. How could it be possible that an ecosystem that took millions of years to evolve could be so devastated in just a few centuries? Chickens of course were only a tiny part of it. Next time I’ll consider how they and their human companions changed Hawaiʻi forever.

A modern convention is to say it was humans, not chickens, who first arrived in Hawaii from Polynesia, but without witnesses noting who got off the boats first, I’m giving the birds the benefit of the doubt.