(Listen to the radio version here.)

This past weekend, Russ and I made a 1,250 mile round trip to Douglas, Michigan, to celebrate the hundredth birthday of Joan Brigham, a woman I’d spent time with maybe half a dozen times 50 years ago.

Russ and I lived in Michigan barely over a year after I became a birder, and I went to the Fenner Arboretum where Joan worked only a handful of times—it wasn’t close to campus. Besides those visits to the arb, I went on two Capital Area Audubon Society (CAAS) weekend field trips which she was leading—they were carpooled, and Russ and I drove ourselves in our Pinto, so we only spent time with Joan on these while the group was actually out birding. So the time I spent with her probably totaled less than the time Russ and I spent in the car to get to and from her party this weekend.

If Joan and my time together could be measured in minutes and hours, not weeks or years, why on earth did Russ and I travel so far to honor her? The minutes and hours I spent with Joan Brigham were some of the most important of my life.

When I started birding, I was very shy and self-conscious, so I bet Joan spoke to me first. I don’t have a single photo of her from back then, but I vividly remember her warm smile. Every time I told her about a new bird, she exuded enthusiasm as if she had just seen her own lifer. On April 29, 1975, when I saw my first Tufted Titmouse, #19 on my life list, at the arb, I remember how urgent it felt to rush to the office to tell her about it. I could count on her warm encouragement, and also on the valuable tips she was constantly giving me—she’s the one who told me where to look for the titmouse in the first place.

On February 4, 1976, she told me to check the conifer treetops and bare birch branches—redpolls had just arrived! Her eyes sparkled when I returned to the office to tell her I’d found them.

On May 1, 1976, Russ and I were on the car-pooled CAAS trip to see the last prairie chickens in Michigan, meeting Joan and the others in a gravel parking area in what seemed like the middle of nowhere while it was still pitch dark. We kept our flashlights pointed straight down as we walked silently to the observation blind in the dark. A handful of prairie chickens started gathering as the sky started growing pink. As we watched and listened to these splendid birds dancing and booming in the growing light, I could see Joan’s excitement and sorrow both, heightening my appreciation of these magnificent birds even as I could feel more deeply the enormity of loss that so few remained. Within the next few years, they’d be gone—entirely extirpated in Michigan.

As it grew light, the prairie chickens disappeared but we lingered a bit until every one of us had heard the lovely tones of Upland Sandpipers and snipe—a few of us even managed to see them aloft.

I was thrilled, my excitement enhanced by Joan’s. These were hardly new birds for her, but her deep pleasure in every bird reinforced my own growing understanding that a bird didn’t have to be a lifer to be thrilling.

When our group moved on for a breakfast break at Hartwick Pines State Park, Joan’s eyes sparkled with delight as she showed us a Brown Creeper nest tucked into a loose wedge of pine bark. She carefully explained the differences between the Chipping Sparrows’ trilling songs (which I’d heard before) and the somewhat slower, more musical trills of Pine Warblers. When a flock of Evening Grosbeaks flew in, she’s the one who heard and pointed them out.

I was in a state of euphoria seeing so many new and exciting birds. When we made it up to Whitefish Point for lunch, I didn’t want to waste time indoors; as the rest of the group sat down to lunch, I grabbed my sandwich and headed back to the parking lot. Suddenly, a tiny, gorgeous little sparrow in the sparse grass caught my eye. I riffled through the pages of my field guide to confirm what I was seeing—my lifer LeConte’s Sparrow!

When I’d studied it and made absolutely sure I wasn’t confusing it with any other sparrows, I ran to the building to tell the group; they were sitting with the man in charge of the banding program. He instantly said it was “impossible”—there had never been a LeConte’s Sparrow report from Whitefish Point. I’d been extremely careful figuring it out but didn’t have much confidence in my own judgment in the face of an experienced, very assertive person doubting me. As I tried to explain why I thought it was a LeConte’s Sparrow, Joan immediately stood up, said she knew me to be a careful observer, and that this would be worth checking out. The rest of our group followed, the doubtful bander bringing up the rear. That lovely little sparrow had cooperatively stuck around, and when the bander realized that yes, this was indeed a LeConte’s Sparrow, he charged back into the building yelling at staff to grab the banding nets—he’d just found a LeConte’s Sparrow! Joan rolled her eyes and winked at me, signaling that even if he was taking all the credit, she knew who had really found the bird first. That was one of the most satisfying moments of my life.

A month later, Joan led another the CAAS field trip back to Hartwick Pines. We spent the day exploring the park, and at dinner she told me exactly where I’d find my lifer Pileated Woodpecker—Russ and I strolled there after dinner.

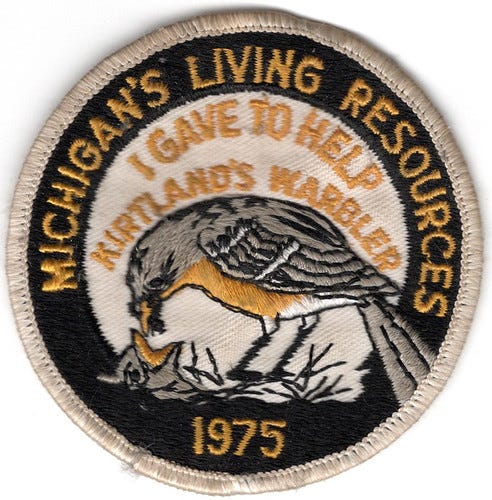

The next morning, we met a U.S. Fish and Wildlife employee at our motel’s meeting room, and after a brief informational session, he led us out to see Kirtland’s Warbler, Prairie Warbler, and an unexpected Northern Mockingbird all in the same place.

Joan’s excitement and joy, along with her insights about these wonderful birds I was experiencing for the first time, modeled how joyful and fulfilling a lifetime of birding would be, enriching for my mind and heart both.

I think that field trip was the last time I saw Joan Brigham for decades—that was the week we moved away from Lansing for Russ to start his Ph.D. program in Madison, Wisconsin.

Then, in April 2019, when I mentioned on Facebook that Russ and I were headed to Florida, Heather Nagy, a friend from down there who just happens to be extremely close to Joan Brigham, suggested that we spend a day birding with her and Joan who, since her retirement, spent her winters in Clearwater. As it turned out, Joan had to pass on the birding that day, but after Heather took Russ and me to some great spots, we got together for a little while with Joan. That was splendid!

And now we got to spend a bit more time with her at her party, so I could finally tell her how much she has meant to me.

It’s hard to express just how much Joan Brigham gave me, and how much my birding life has been defined and enriched by her example and mentoring. People often talk about our “spark bird”—the bird who sparked our interest, transforming us into a birder. Joan Brigham was my “spark birder.” I can’t possibly thank her enough.

What a story! Being from MI (Bellevue, on a dairy farm), Hartwick Pines was a place our family stopped when able to get away from the cows! Laura, you are my Joan! Just wish I'd started birding earlier in life, but glad I have you to check in with! Thank you dear Friend! Polly

A beautiful story of how much so few minutes can mean in a life. Thank you, Laura.