(Listen to the radio version here.)

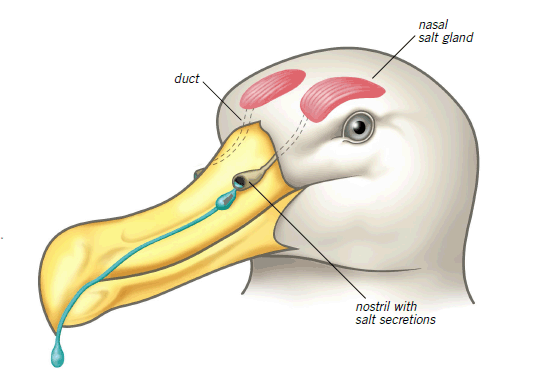

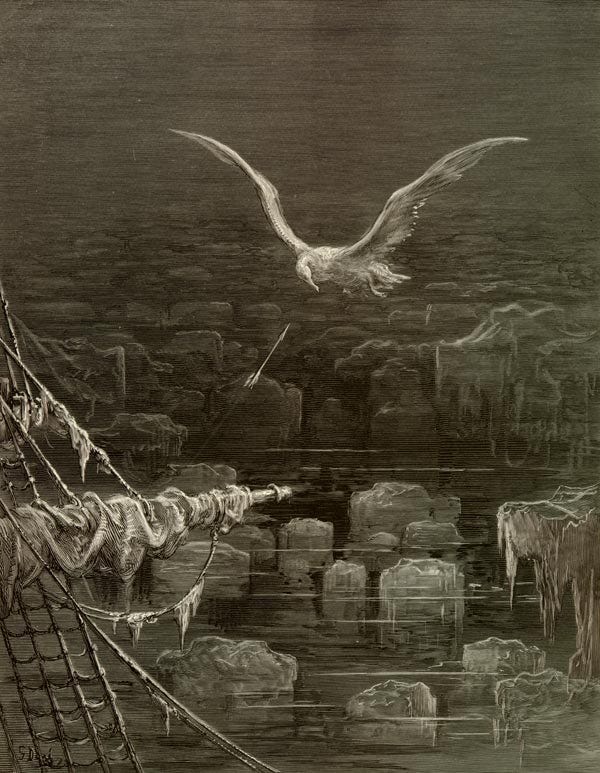

The seabird that we call the albatross—the one memorialized in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner—belongs to the order Procellariiformes, nicknamed “tubenoses.” Virtually all birds have an enlarged “nasal salt gland,” usually located at the base of the bill above the eyes. In most land birds and freshwater birds, this salt gland isn’t functional. In the case of loons, which spend summer in fresh water and winter on the ocean, it swells up the moment the bird tastes saltwater.

The salt gland’s job is to remove excess salt from the bloodstream; as it pulls the salt out, it creates a 5 percent saline solution that drips out or is forcibly ejected from the nostrils. If my calculations are right, that means an albatross’s “tears” are almost 7 times saltier than ours.1 In albatrosses and other tubenoses, the salt gland is always active, and the salty secretions flow out of the body through those tubes.

The order Procellariiformes includes shearwaters and petrels, storm-petrels, and albatrosses.

All tubenoses spend their lives over oceans, coming to remote islands and atolls, and some to rocky coastlines, only to breed. They seem to float effortlessly over the water, using dynamic soaring and slope soaring to cover great distances with little exertion. Within the order, the albatrosses, which belong to the family Diomedeidae, have the most exceptionally long wings.

Albatrosses eat mostly squid, but also take fish, fish-eggs, and crustaceans; they scavenge as well as picking up live prey, making them exceptionally vulnerable to plastic waste strewn on the ocean, which they apparently mistake for food. Nestling albatrosses have been found dead, their entire digestive tract filled with plastic.

Most tubenose species are declining, and the order includes a great many globally endangered and threatened species. Every one of the 22 species of albatross recognized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature is listed at some level of concern; 3 species are Critically Endangered, 5 are Endangered, 7 are Near Threatened, and 7 are Vulnerable.

What is causing their decline besides the horrible losses to plastic? Military operations on some remote islands have decimated local populations. Overfishing and climate change have reduced their food sources, and commercial fishing kills them directly as by-catch. Marine pollution poisons them. Feral cats, rodents, and other introduced predators destroy eggs and chicks on their remote breeding grounds.

Sometimes albatrosses are killed out of sheer bloodlust, and not just by Ancient Mariners. In December 2015, six students and recent graduates of a prestigious Honolulu prep school on a camping trip in westernmost Oahu used a bat, a machete, and a pellet gun to kill and dismember at least fifteen nesting Laysan Albatrosses; researchers found seventeen nests with smashed, dead, or missing eggs. The culprits chopped off the birds’ feet to collect their I.D. bands as souvenirs and posted photos of the mutilated birds on social media. They also stole $3,100 worth of seabird monitoring cameras and sound recording equipment. State and federal investigators testified that the rampage set conservation efforts back ten years and caused more than $200,000 in damage. Three of the killers weren’t charged at all. Two were charged in juvenile court, the disposition kept confidential because of their ages. The sixth, 18 at the time of the rampage, could have been sentenced to a year in prison and up to $7,000 in fines for the two albatrosses he admitted killing, but he was given a 45-day sentence for the killings and a $1,000 fine for the stolen property. Nine years later, I still cannot wrap my head around this atrocity and the minimal consequences for the killers. It’s embarrassing to belong to the same species.

Most albatrosses spend their lives in the South Seas, but the Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses, both small by albatross standards, are exceptions. A full 99.7 percent of all Laysan Albatrosses nest in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands, with the largest colonies on Midway and Laysan Islands. When Russ and I visited Hawaii this past February, we saw Laysan Albatrosses on both Oahu and Kauai, and Black-footed Albatrosses on Oahu. Some of Oahu’s Laysan Albatrosses nest on a golf course!

Small populations of Laysans are found on the Bonin Islands near Japan and the French Frigate Shoals, and some are beginning to colonize islands off Mexico and in the Revillagigedo Archipelago. When away from the breeding areas, Laysan Albatrosses range widely from Japan to the Bering Sea and south to 15°N.

One individual Laysan Albatross named Wisdom is famous as the oldest known wild bird on earth. She was banded as a nesting adult on Midway Island by Chandler Robbins in 1956, when she’d have been a minimum of 5 years old, so she’s at least 74 years old now, making her the only known wild bird who is older than me.

A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service volunteer documenting and researching birds on Midway Island Atoll National Wildlife Refuge discovered Wisdom, her mate, and their newly laid egg on her trusty old nesting spot on Midway on November 26. Dan Rapp took some wondrously charming photos of the pair before Wisdom flew back to sea to feed. The parents take turns incubating their one precious egg, which, assuming nothing goes wrong, should hatch in 65 days or so—at the end of January or very early February. Then, if all goes well and the baby survives, it’ll leave the island at some point between mid-June and early August. For a 74-year-old mother to succeed in raising a chick all the way to fledging in such an increasingly inhospitable world, that would be a miracle of the highest order.

An albatross’s salt gland secretions are 5 percent salt, which I think makes them about 2000 mOsmol/L. Our tears should be roughly 300 mOsmol/L—the condition called “dry eye” is diagnosed if someone’s tears are excessively salty, which is considered more than 316 mOsmol/L. (If I calculated this wrong, let me know!!)

It IS embarrassing to belong to the same species, our plastics being another scourge. But the redeeming factor is that there are so many that care, such as yourself, Laura, and you and they constantly come through BIG TIME in the spirit of Dr. Robbins (and I sense you miss him now more dearly than ever) for birds and nature. The scientists on Midway are wonderful, I having the pleasure of seeing one young one on a private Zoom presentation describing conservation activities there to us and his absolute, unmitigated passion for them.

What wonderful, beautiful birds. Thank you for sharing!

~Toshia