(Listen to the radio version here.)

More than anything else I do, I hate making mistakes. I vividly remember the summer when I was five, going with my father to the convent one Sunday morning to meet the principal. Sister Suzanne was the one who would decide whether I’d start first grade before my November birthday or wait a full year, until I was six. She asked me what my address was, a simple enough question—we lived at 116 Whitehall. But somehow instead of saying one-one-six or one-sixteen, I garbled it and said one-one-sixteen.

My dad kicked me under the table as he cut in to correct me, and I was mortified—how could I get my own address wrong? I almost started crying, but Sister Suzanne looked me straight in the eyes and said that a lot of second and even third graders got their addresses mixed up sometimes. Everything else went okay and I got to start first grade that year. But somehow the embarrassment of that mistake 67 years ago has never dissipated.

When I was in third grade and my teacher called on me to read a few paragraphs from a story in our reader, I mispronounced Solomon like the familiar word “salami.” Mrs. Bepko as well as the kids laughed at me, and I can still feel my cheeks burning.

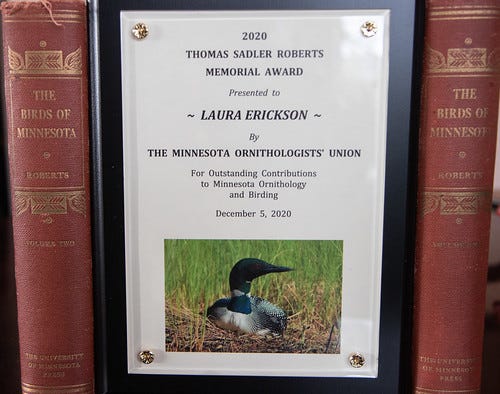

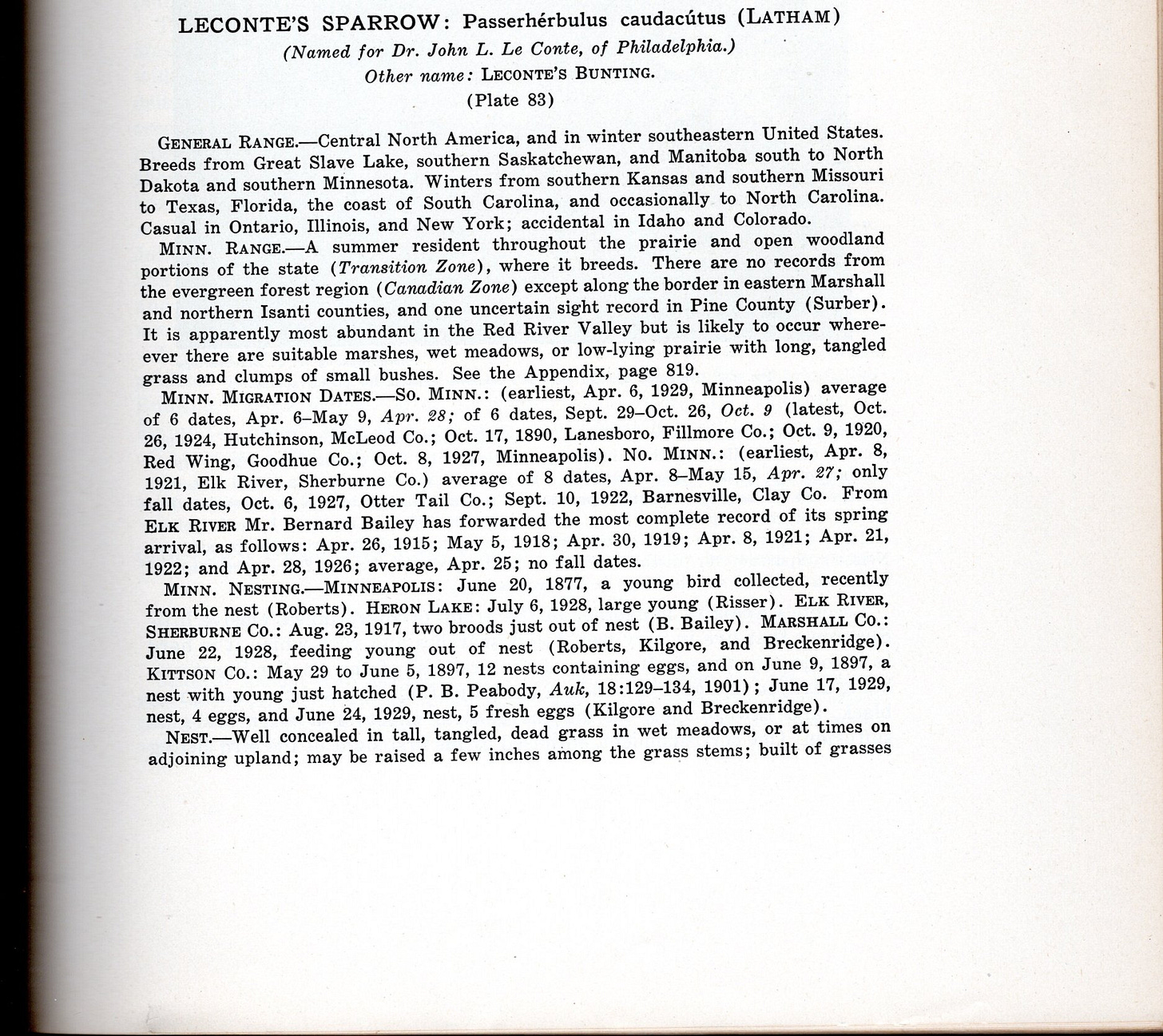

I’ve always taken great pride in being accurate. Overall, I have a pretty good track record, but I’m as mortified as ever when I make a mistake. When I was writing my Field Guide to the Birds of Minnesota for the American Birding Association, the editor sent me a message late one night that my entry for Le Conte's Sparrow—one of my favorite birds of all—had an error. I’d written:

This elusive little bird … described by Thomas Sadler Roberts as having a warm, old-gold suffusion like a twenty-dollar gold piece…

He said Roberts was describing just the immature plumage. I’d been paraphrasing Roberts’s description for years, so I felt both chastened and mortified, as thoroughly embarrassed as that child mixing up her address or talking about King Salami.

To figure out how I got it wrong, I pulled out my trusty old copy of Roberts’s The Birds of Minnesota and looked up the Le Conte's Sparrow entry. What he wrote was too long to quote for a brief field guide entry, but I’d been paraphrasing it accurately:

It is one of the prettiest of the smaller sparrows, being arrayed in a garb of subdued but beautifully disposed chestnut, gray, black, and tawny color, having the general effect of a warm, old-gold suffusion. One correspondent, enthused by his first sight of the bird sitting close at hand on a bat of broken-down, dead vegetation, remarked that his first thought was of a twenty-dollar gold piece!

I was so relieved that I immediately scanned the pages and sent them to my editor.1 He didn’t respond but did leave my description intact.

Some birders relish catching others making mistakes, especially about bird identification. Oddly enough, even though my field guide was very well received, I don’t take particular pride in my identification skills—I’m far more focused on behavior, natural history, and conservation, so when I’m leading a field trip and call out a bird, if someone else calls out that it’s a different species, I seldom feel even a trace of embarrassment. In the field, it’s more important to get everyone looking at the bird than to wait until we’re 100 percent certain about its identity. An incorrect ID will usually get sorted out soon enough.

Nevertheless, we birders can’t help but want to be fast and accurate both, every single time. On October 17, 1987, when I was counting birds at the Lakewood Pumping Station long before cell phones and text messaging, someone ran up and told me that Kim Eckert had found a Yellow-billed Loon at Brighton Beach, and it seemed to be making its way up the shore. This was just the third state record of this Arctic species, so Kim (still at Brighton Beach) told her to tell me it would be okay to abandon my post to look for it. Instantly I zipped into my car and headed off. Since it was supposedly working its way toward me, I stopped at the first pull-out on the lakeside to scan. Two other very experienced and knowledgeable birders were already there looking, and a fifth joined us.

We quickly found a bird way way out in the lake, and I got it in my spotting scope. Yep—long, low-slung grayish body, yellow bill subtly upturned. Yay! Everyone took a look, and everyone was thrilled. After we had each seen it long enough to confirm the identification, when it was my turn at the scope again, I took a longer look. And now something seemed off. Suddenly I realized this wasn’t any kind of loon at all, much less the least likely species in Minnesota—this was a young Double-crested Cormorant.

I didn’t blurt that out. I was far more hesitant, saying maybe this might be a cormorant. And yep—after another look, everyone agreed. I felt silly for not recognizing it right off the bat, but oh, well—the real deal might still be somewhere between here and Brighton Beach, and my immediate priority was to find it. But everyone else was stuck in mortification mode until one of them made us all promise never EVER to tell anyone about this mistake.

I’ve mercifully forgotten who else was there, so I’ve never exposed anyone else for having made that mistake. We all headed to Brighton Beach where the real Yellow-billed Loon still was hanging out, much closer to shore than that cormorant.

This may have been embarrassing, but it was an instructive mistake that I’ve mentioned many times when leading walks and either helping with cormorant or loon identification or when someone is embarrassed about getting an ID wrong.

Everyone makes mistakes. What determines what kind of human being we are as well as how much of an authority we really are is in how we deal with correcting our own mistakes and how we point out the inevitable mistakes others make. At least this is pretty low-stakes when it comes to birding. I wish more politicians understood how to admit, and correct, mistakes, too.