The Tiniest Bird in the Universe

The Bee Hummingbird actually is bigger than a bee, but not by much!

(Listen to the radio version here.)

I used to teach middle school and junior high, and then I became a mother of children who worked their way to middle school and junior high, so I know firsthand how much kids are drawn to superlatives. Just about any kid can instantly name the fastest bird in the world, the Peregrine Falcon…

… and the biggest bird in the world, the ostrich.

Kids are of course drawn to big and fast, but many of them also know what the tiniest bird in the world is—the Bee Hummingbird. But whether they’re a kid or adult, most people I talk to don’t realize the Bee Hummingbird is endemic to Cuba, meaning Cuba is the only place in the known universe where wild Bee Hummingbirds can be found.

The Bahama Woodstar and Ruby-throated Hummingbird occasionally show up in Cuba, but only two species of hummingbirds are regular, year-round species there. The Cuban Emerald, fondly called the zunzún by Cubans, doesn’t quite live up to its name, because it’s also found in the Bahamas.

Cuban Emeralds are extremely easy to see. We saw them every single day during my trip to Cuba last month, often several times a day. They’re gorgeous birds, the males glittering in the sunshine even more beautifully than the gemstone they’re named for.

As with most hummingbirds, females are more dully-colored than males, but female Cuban Emeralds are also much shyer—virtually all the Cuban Emeralds I saw on this trip were males, and of the bazillion photos I took of the species on this trip, despite the fact that I was trying hard to get photos of both sexes, I didn’t get a single picture of a female.

The tiny Bee Hummingbird is called the zunzúncito (meaning tiny zunzún) by Cubans.

The Bee Hummingbird nest, the size of a thimble, has the smallest diameter of any bird nest, though it’s similar in volume to the nest of the barely larger, second smallest bird in the world, the Vervain Hummingbird of Jamaica and Hispaniola. (I hope I can see that one later this year!)

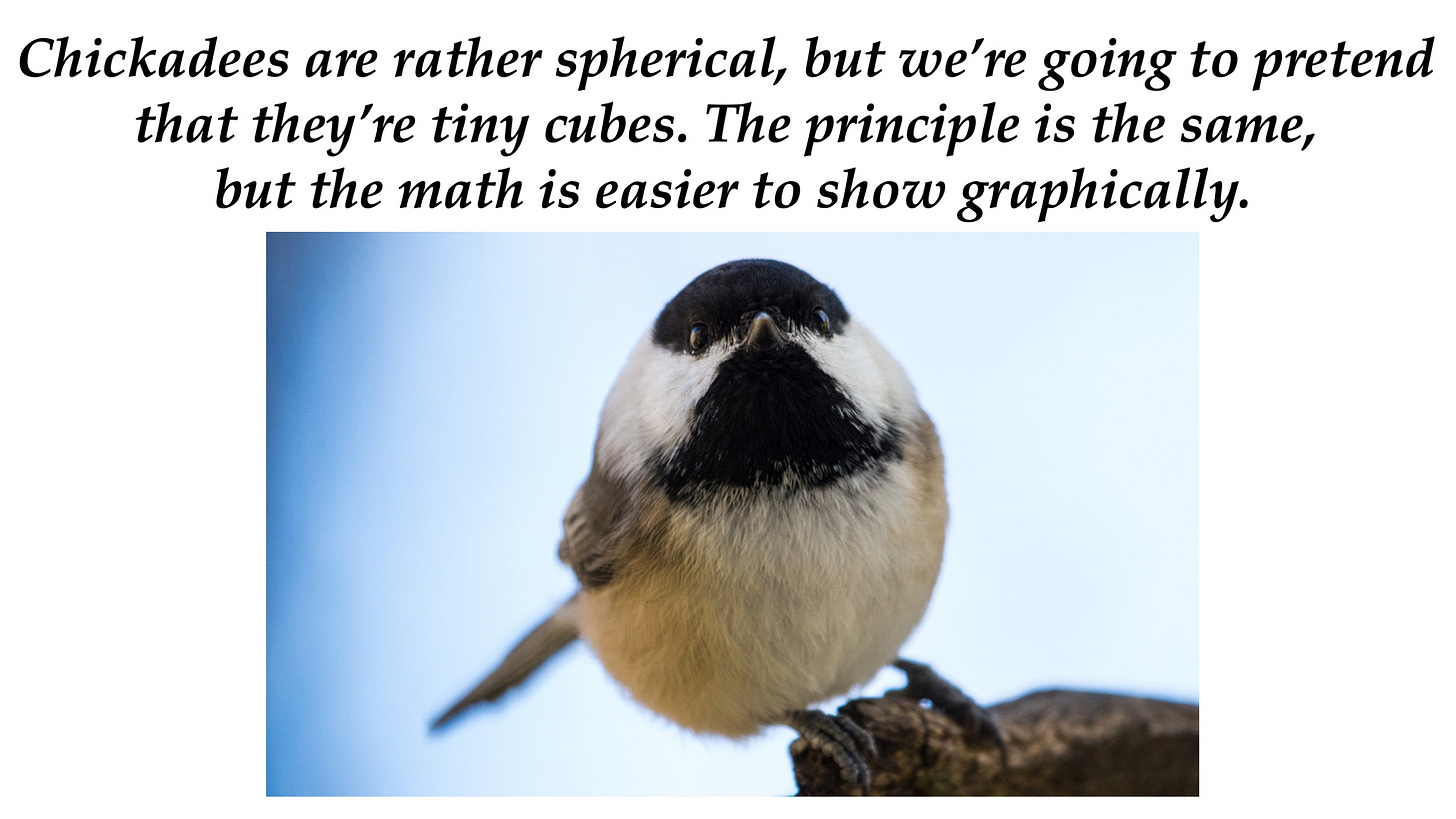

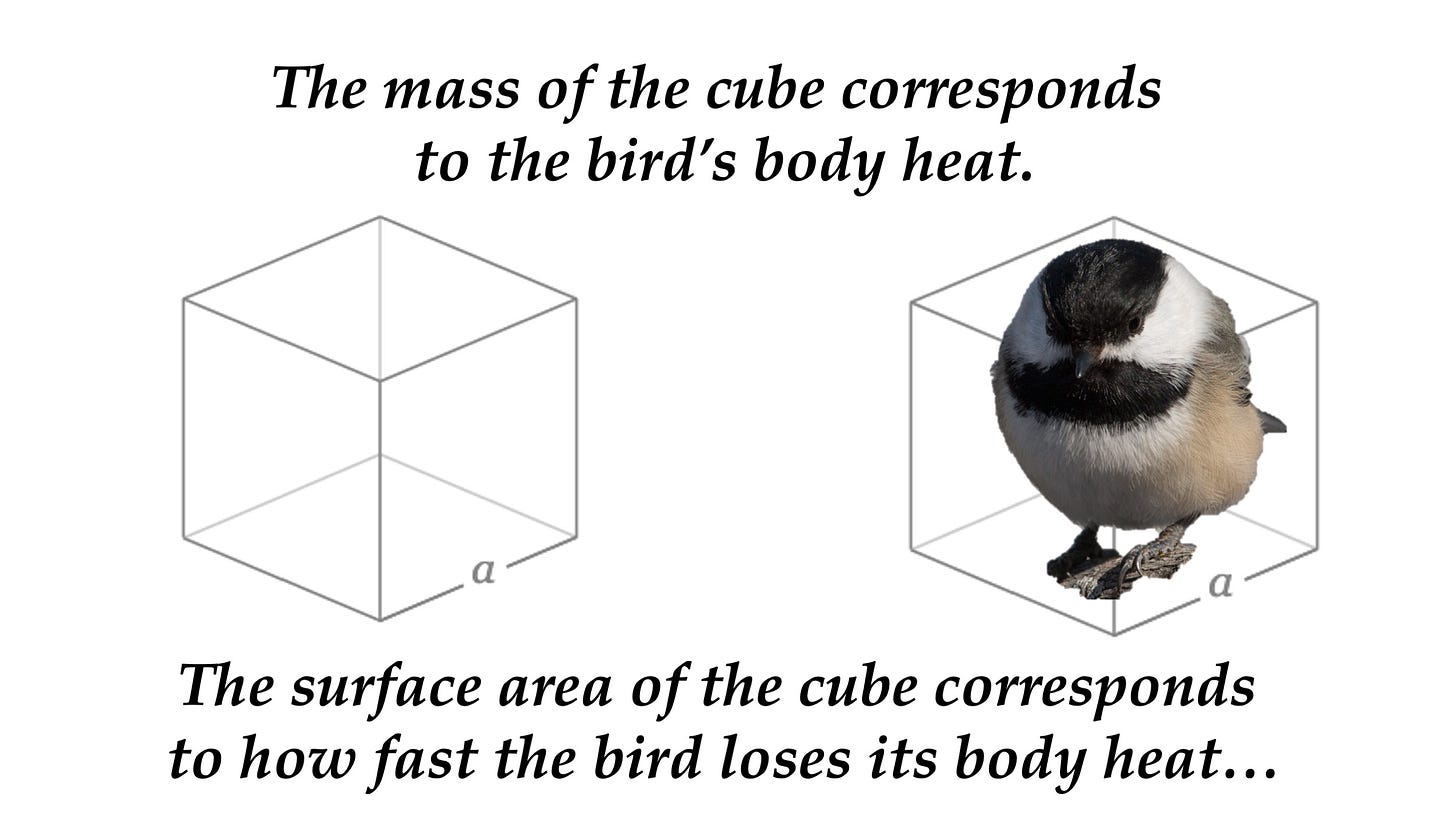

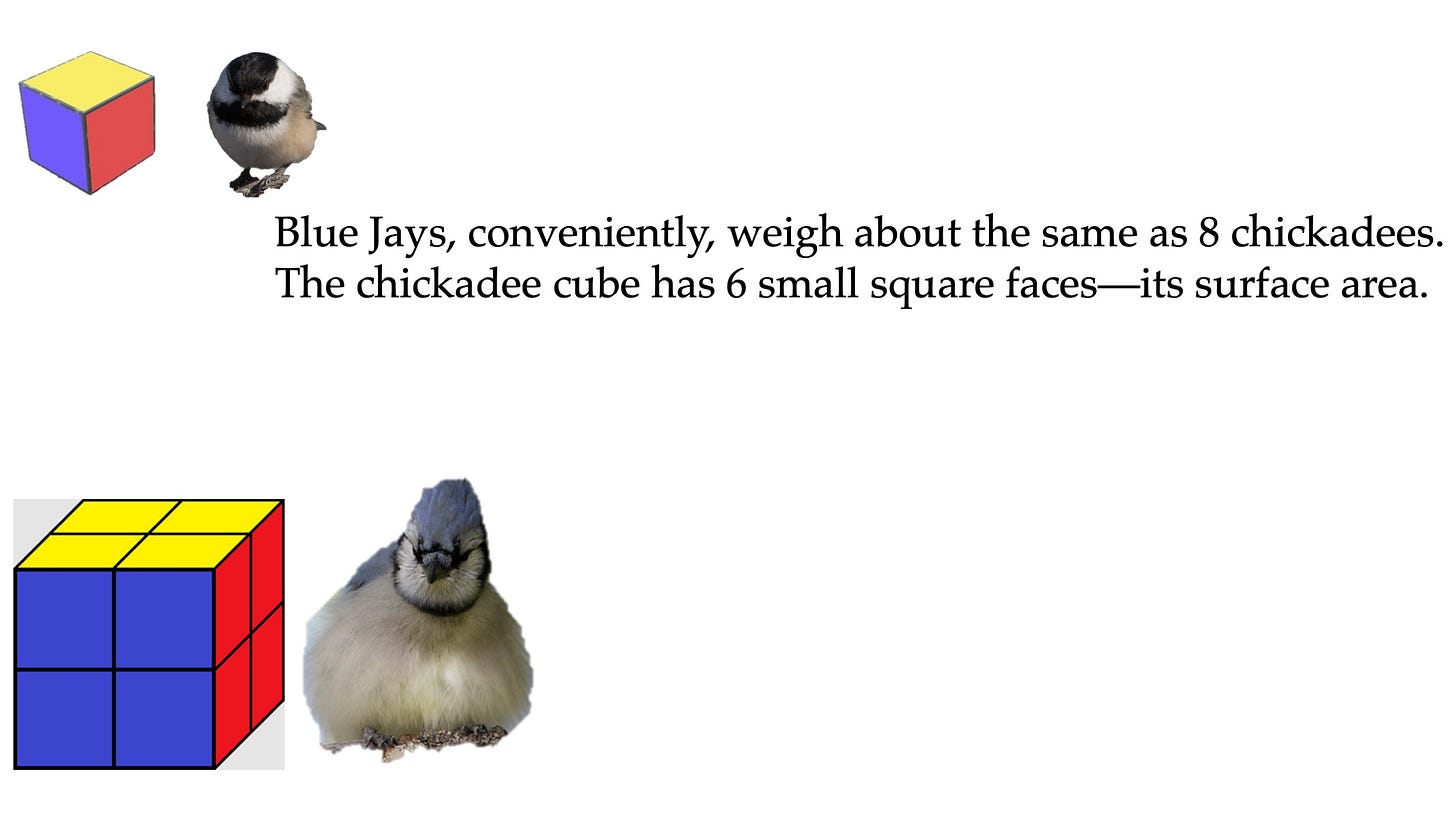

Bergmann’s rule, which I learned about in high school biology, states that within a taxonomic group, populations and species of larger size are found in colder environments while those of smaller size are found in warmer ones. This rule seems to hold most strongly for warm-blooded animals, though it has a lot of exceptions. The largest mammals of all are the whales, many of which do indeed live in temperatures only a few degrees above freezing, but the largest birds of all, the ostriches, live in sub-Saharan Africa and the Horn of Africa, where temperatures can be exceedingly hot.

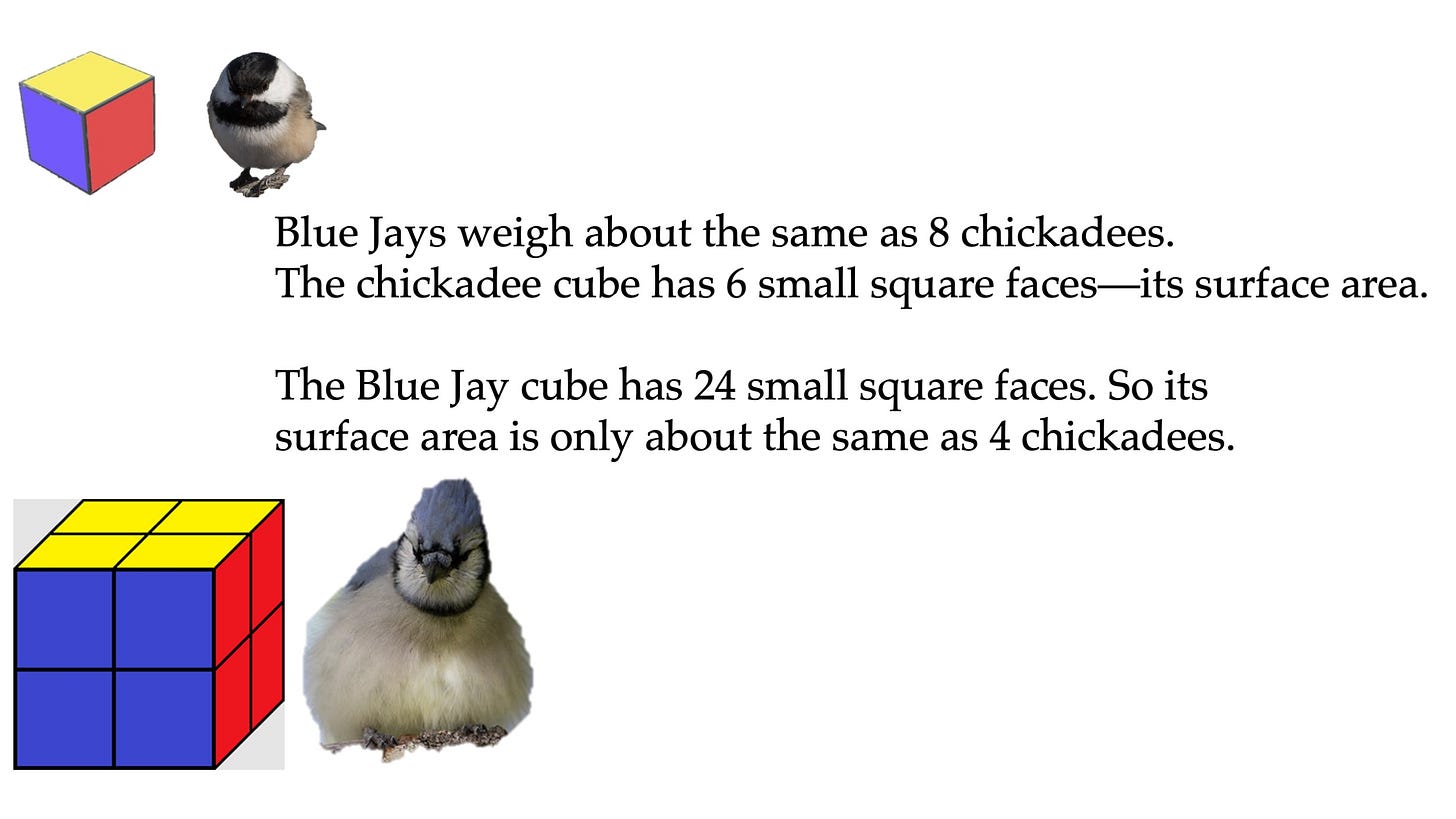

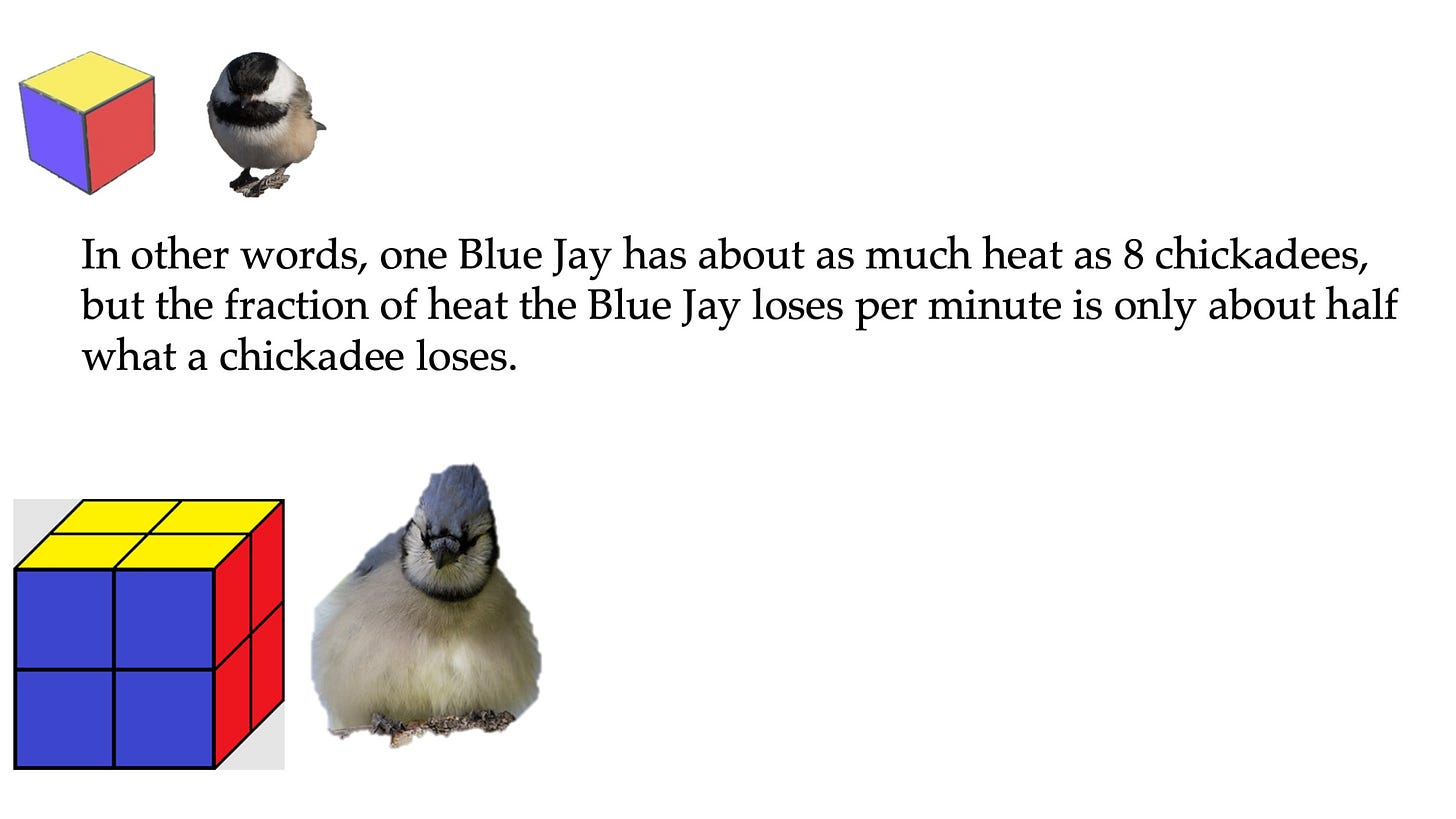

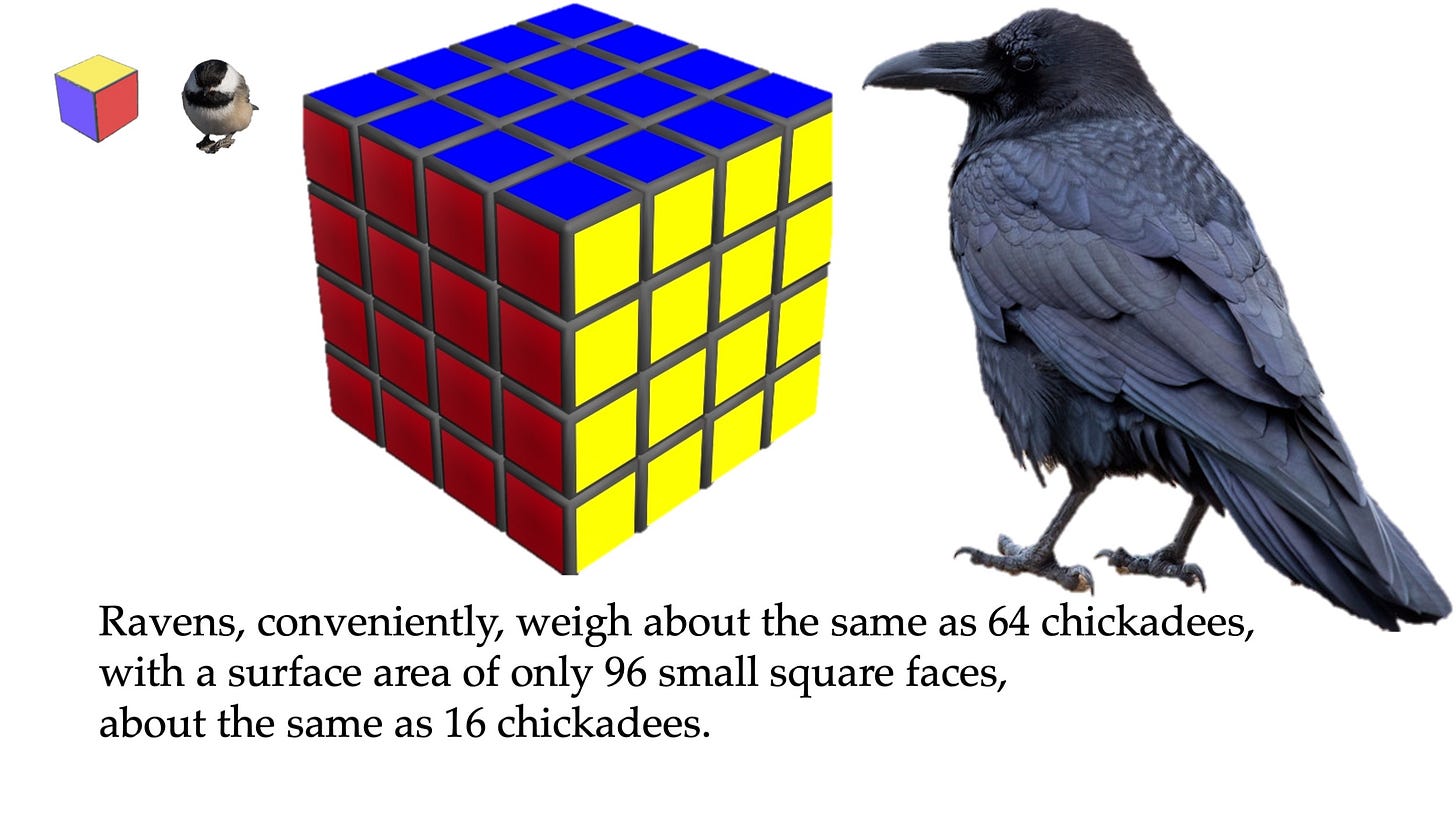

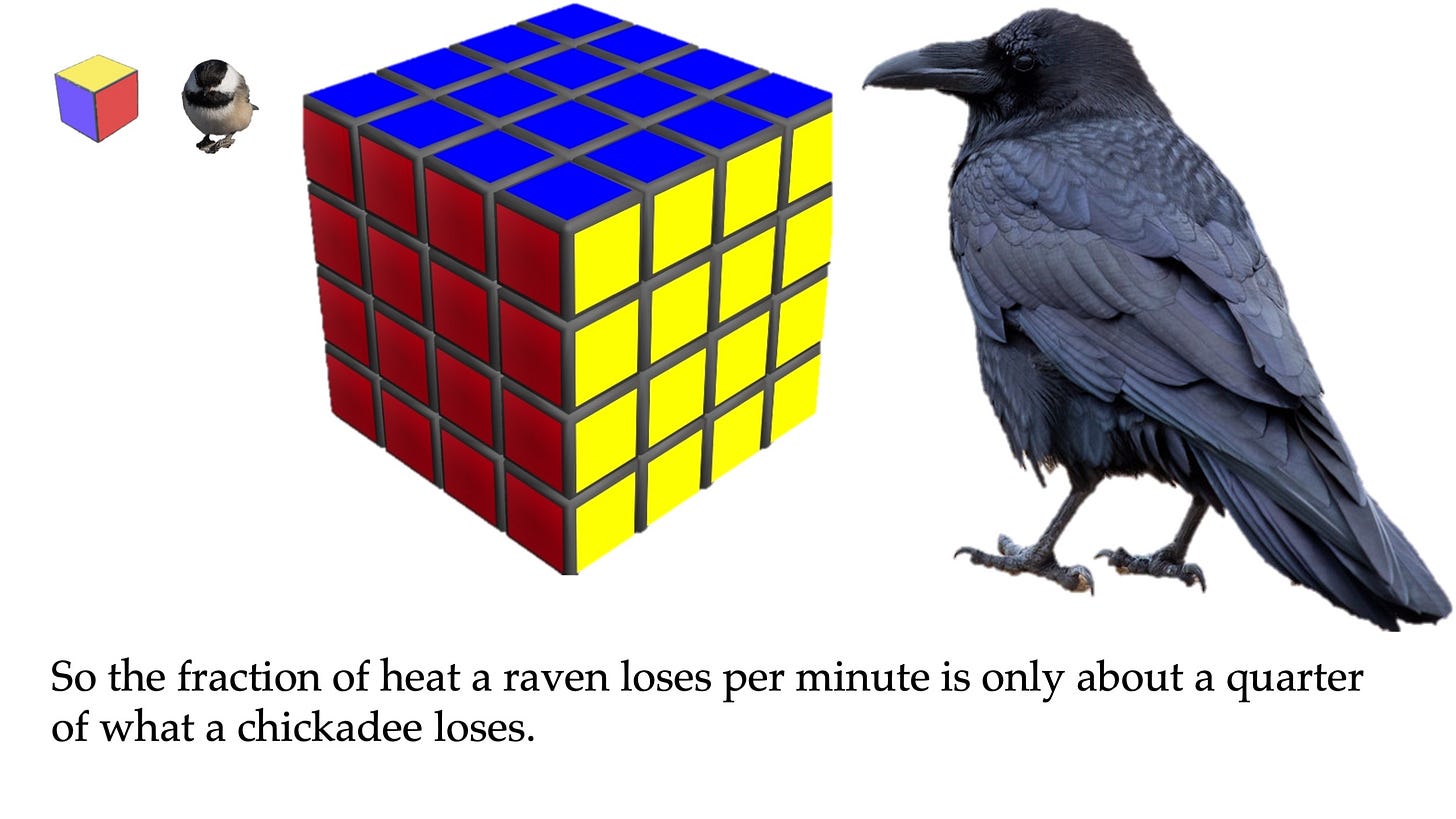

As I learned in high school math, the smaller a sphere or cube is, the larger its surface area relative to its volume. When the environmental temperature is lower than a warm-blooded animal’s body temperature, the animal loses heat to the environment, and the larger the animal’s surface area is relative to its mass, the faster its body heat is released.1

One of the tiniest hummingbirds in the United States, the Rufous Hummingbird, is also the one that nests farthest north, all the way up in Alaska, which certainly breaks Bergmann’s rule, though hummingbirds take advantage of torpor during cold conditions, becoming inactive and dropping their internal temperature so they can reduce the amount of heat loss. It’s nevertheless amazing how cold the temperatures can be for these tiny birds.

One Rufous Hummingbird appeared in my yard on November 16, 2004, remained through a blizzard and single-degree temperatures, and finally left at mid-morning on December 3.

In 2021, another appeared down my block in late October, showed up in my yard within minutes of my setting out feeders on November 8, and stuck around until December 4, breaking the St. Louis County late date record that my previous Rufous Hummingbird had set.

The second one, like the first, left after eating its fill and the changing weather provided tailwinds for it to head south.

The Rufous Hummingbird may be the tiniest long-distance migrant in the world, but the even tinier Bee Hummingbird and Vervain Hummingbird are restricted, year-round, to an area of consistently warm temperatures in the Caribbean, as if trying to prove Bergmann’s Rule correct.

The Bee Hummingbird feeds on several flowers native to Cuba (Wikipedia shows them here) that share important common elements—they’re odorless since hummingbirds don’t have a well-developed sense of smell, are brightly colored to attract nectar-feeders with excellent vision, and have long, narrow tubular corollas, perfectly sized for a tiny hummingbird’s bill while excluding most insects, making the flowers and hummingbird an excellent example of something else I learned about in high school, co-evolution: the flowers depend on Bee Hummingbirds for pollination, and the hummers depend on the flowers for food. Bee Hummingbirds consume up to half their body weight in food (nectar and insects) every day.

When not feeding in these flowers, Bee Hummingbirds spend most of their time in mature forests with thick tangles of lianas and rich in epiphytes. Habitat loss due to development and recent hurricanes has taken a huge toll on Bee Hummingbirds, which are considered near-threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. That’s why unlike the Cuban Emeralds, I saw Bee Hummingbirds on only two occasions during our Cuban visit, both at the same place—Casa Ana Birding, near the Zapata Swamp in Matanzas Province.

This extraordinary garden and feeding station is managed by birding guide Adrian Cobas, who maintains native plants as well as hummingbird feeders to lure gorgeous warblers and other species as well as both of Cuba’s hummingbirds.

Casa Ana is an absolute “must go” destination if you find yourself in Cuba.

We all know that iridescent feathers can change color depending on how light hits them. For example, Mallard heads can appear blue or green depending on the light. If you ground up a few of the tiny gorget feathers on any hummingbird, you’d get a dark gray or brown powder, which is also the color you see when the light isn’t hitting the intact feathers. I have photos of an Anna’s Hummingbird showing the color change from dark brownish gray to brilliant magenta depending on how it was facing the sunlight.

When I examined my Bee Hummingbird photos from this trip, I was astonished by the rainbow of colors the gorget feathers could show depending on the light’s angle, including metallic bronze, greenish, magenta, and brilliant pink.

These photos affirm two of my beliefs: that the joys and pleasures of any trip are extended by the photos we take, and that the idea that bigger is better is patently ridiculous.

wow- the day is shining with their beauty. thank you, laura!!!!!!